As we wrap shooting video of the Lichgate Oak, Stan Rosenthal asks if we want to see live oaks growing in a natural, forested setting. And so this story of the urban forest finds us taking a side trip to bushwhack through wild woods.

He takes us to a property where he, as a forester, conducts controlled burns. Going off trail in a longleaf pine ecosystem, we find the kinds of ground cover plants that benefit from regular burning. He points out a flowering short winged sumac shrub not too far from whorled milkweed. There are oaks growing between the pines as well; here, fire stunts their growth and opens up the canopy overhead, making space for a high diversity of grasses, flowers, and succulent plants. When burned every 2-3 years, such a forest is, as the old saying goes, wide enough for a horse and wagon to ride through for miles uninterrupted.

Whorled milkweed (Asclepias verticillata)

Winged sumac (Rhus copallinum)

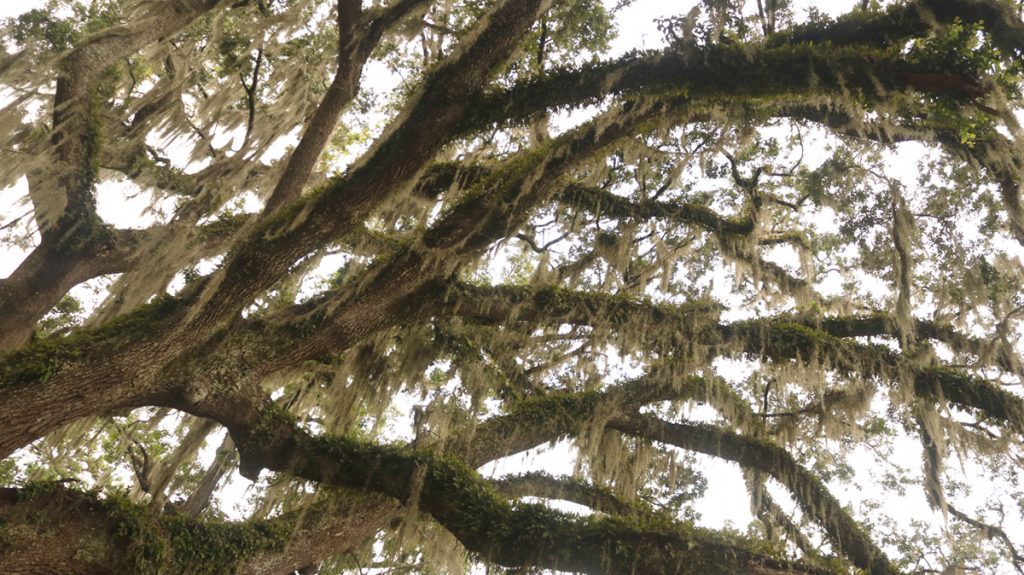

In this environment, we may see a more densely wooded area in the distance. Forcing our way through smilax covered beautyberry bushes and other tall shrubs, we find ourselves in a place wet enough to keep the fire back and let the oaks grow. We’re now standing in a cool cave of live oak branches, looking out over a pond.

I can see why Stan brought us here; these wild growing live oaks are a perfect contrast to the one we just left. Lichgate on High Road has given their majestic live oak all the space it could want to spread out. Its branches are long enough to rest on the ground, and then spring back up and continue on for several more feet. One in particular has dug into the ground, and where it emerges it looks like a separate, horizontally oriented tree.

Live Oaks in the Wild

The live oak branches along the pond touch ground as well. In fact, one tree is mostly branches arching towards the earth, like it’s performing a downward facing dog. This is the space the tree found to grow, crowded in among several other live oaks and hardwoods.

The canopy of a southern live oak (Quercus virginiana) contains its photosynthesizing leaves. The Lichgate oak shows us how wide that canopy can get, as much as 150 feet across. Here by the pond, though, the canopies are all competing for sunlight, and the trees grow accordingly.

“In a wooded area, they’re not going to take this open grown form.” says Mindy Mohrman, Tallahassee’s Urban Forester. “So they’re going to be a little more slender.”

“It’s got to find the sunlight and compete with other trees.” says Sam Hand, Assistant Professor of Extension at Florida A&M University. In a tighter space, its trunk grows more up than out as it tries to get its canopy above the others. Failing that, it might, as we see here, contort itself for a favorable position.

The iconic southern image of a sprawling live oak growing in a pasture, park, or a wide lawn- this is a human creation. These are trees we planted, and with a purpose. As a tree of the urban forest, it exists for its function and its pleasing appearance.

What is the Urban Forest?

Mindy Mohrman explains urban forestry.

“It’s less about forest ecology, as someone might traditionally understand about it, and more about what trees can do for the community, in terms of lowering the heat island, managing stormwater, providing for some habitat, and just providing beautiful community shaded spaces.”

Mindy Mohrman, Tallahassee Urban Forester.

We mentioned in part one of this story that Tallahassee completed an Urban Forest Master Plan in 2018 (PDF here) to guide them in accomplishing the goals Mindy lays out above. Part of that plan was making an inventory of trees in our urban canopy. Here is the top ten, based on a sampling of 3% of trees on public land:

- 15% Laurel Cherry (Prunus caroliniana)

- 10% Water Oak (Quercus nigra)

- 7% Laurel Oak (Quercus laurifolia)

- 7% Southern Live Oak (Quercus virginiana)

- 6% Camphor Tree (Cinnamomum camphora) *Invasive

- 5% Common Crape Myrtle (Lagerstroemia indica) **Nonnative

- 4% Flowering Dogwood (Cornus florida)

- 3% Southern Magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora)

- 3% Black Cherry (Prunus serotina)

- 3% Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua)

The urban canopy covers 55% of Tallahassee, down from 61% in the mid-1980s. Impervious surfaces, such as roads and buildings, increased from 9% to 17% in this time as well. Still, this is considered a high quantity coverage. The problem, as Mindy explains, is the quality of the trees.

“Out of those top five,” Mindy says, “the live oak is really the only high value, long-lived urban tree species that we have.”

Diversity of Tree Species in Tallahassee’s Urban Forest

Taking a closer look at the top six, we see that the top four are native plants.

People like tree number six, crape myrtles, as an ornamental tree. As a nonnative, it has less ecological value than others on the list. But as we’ll soon see, it has positive qualities. The camphor tree (number five) is invasive, and will grow prodigiously wherever we don’t cut it down. When Apalachee Audubon removed invasive plants from Lake Elberta late last year, it was the number one species they cut from the woods at the edge of the park, growing unchecked along a drainage ditch.

We’ll take a closer look at why the top three trees are less favorable, and why the live oak is such a high quality tree, in the sections below. First, we’ll look at the composition of the canopy overall, and whether or not we should be planting way more live oaks to improve it.

“First off, don’t just plant one kind of tree. You set yourself up for disaster,” says Stan Rosenthal. “If it’s seven percent of the canopy, as you say Mindy had come up with, that’s great. Ten percent’s probably okay. I wouldn’t do fifty.”

The Urban Plan specifies that no tree species should exceed ten percent of the canopy. Currently, only cherry laurels are that highly represented, at 15%. After cherry laurels, you’ll notice that the next three species are all oaks. The plan calls for no genus to represent more than 20% of the total, and right now Quercus is 26%. Imagine a blight specific to oaks making its way to Tallahassee; over a quarter of the urban forest would be at risk. What we want is a diversity.

More specifically, we want a diversity of trees that are long lived, and of strong wood.

Storm Resiliency

Hermine. Irma. Michael. Our large canopy has taken a beating over the last three years, with hurricanes sending trees and limbs onto homes and power lines. Strong storms are hitting us more frequently, and the Urban Forest Master Plan (UFMP) aims to make our tree cover more resilient.

“Over half of the population of public trees in the city are estimated to have either low or medium-low wind resistance, making them especially susceptible to damage in storm events. In the upcoming years, severe weather events are only expected to increase in frequency (National Climate Assessment 2014).”

Tallahassee Urban Forest Master Plan (page 6)

Per the report, 37% of the trees in Tallahassee are considered to have low resistance to strong winds, and 16% are medium low resistance, compared to 22% with high resistance (page 34). The top three species in our canopy are in that low resistance category, while live oaks are high resistance. Other high resistance trees include dogwood, southern magnolia, four species of holly, cypress trees, and even the nonnative crape myrtle. You can see a full list of most and least storm resistant trees on this UF IFAS blog post.

There are also the matters of tree positioning and maintenance. According to the UFMP, 58% of trees conflict with power lines. And even the normally strong limbed live oak can become a liability if not properly maintained. Proper pruning reduces the threat of falling limbs. But another major threat to the overall health of the tree goes back to positioning. Many trees are planted where their roots don’t have the space they need to expand. In fact, the report estimates that 70% of trees are in conflict with “hardscapes.” Sidewalks, parking lots, driveways, and underground utilities are too often in a position to impede or prevent water from reaching roots.

Stormwater Management

So we see that it can be challenging for trees to find the space they need in an urban environment, and few trees here need as much space as live oaks. Their roots can extend a third as far past their considerable canopies, which, as I mentioned earlier, can cover 150 feet. Following the “right plant, right place” principle, this is a tree for large yards, parks, or open agricultural land.

When in the appropriate setting, that sprawling canopy offers a host of benefits. One such benefit relates, once again, to storms.

“The larger a canopy, the more stormwater a tree can soak up,” says Mindy Mohrman of live oaks. “It really depends a lot on the climate how much water a tree can uptake, but it could be up to several hundred gallons a day.”

This informative article from Forester Media explains how urban trees reduce runoff. Leaves in a tree’s canopy intercept rain as it falls. Some of that evaporates, and returns to the atmosphere. The rest slowly drops through the canopy, creating a more manageable flow of water than if it landed directly on the ground. The article also sites research showing that trees take up nutrients that might otherwise run off into waterways, increasing algae blooms.

Tallahassee is in the springshed for Wakulla Spring, and stormwater runoff gathers excess nutrients and pollutants from lawns and streets, draining into a multitude of waterways that end up feeding the spring. Large trees additionally reduce this runoff by drinking it up, and their roots facilitate water flowing downward into the aquifer rather than onto streets. North of the Cody Escarpment (roughly the North Florida Fairgrounds), water soaking into the aquifer is filtered by thick layer of red clay.

Carbon Storage and Sequestration

These big, thirsty trees aren’t just drinking up water. Southern live oaks are among the most efficient trees in our area with regards to carbon storage and sequestration.

Half of the dry weight of any tree’s wood is carbon; this is the carbon the tree stores. Carbon sequestration, on the other hand, is the amount of carbon a plant takes in over a given time, the amount it grows, the weight it adds. If a tree adds 100 lbs of dry weight in a year, then it sequestered 50 lbs of carbon.

So how effective is the southern live oak compared to other trees in the urban canopy?

For one thing, it is considered a fast growing tree. And it has dense wood. Sam and Stan tell me that the wood weighs 70 lbs a cubic foot, wet. “Two of those weigh as much as a lot of people,” Sam says. This is a tree that puts on a lot of weight year by year.

It’s also a long lived tree, reaching 300 years under the right conditions. And it’s just large. By comparison, laurel oaks are also fast growing trees, and effective at sequestering carbon. But they live less than 100 years, and, while they get taller than live oaks, they have smaller mass. Over time, the live oak more effectively stores carbon.

A study of urban trees and carbon co-authored by the US Forest Service’s David Nowak places southern live oaks in the top echelon of trees in regards to carbon storage. Other large, fast growing, and long lived trees in our area include sweetgum and bald cypress.

Habitat for Plants

So far, we’ve looked at trees as organic components of an urban system. The UFMP places the highest value on trees that won’t cause damage or endanger lives during weather events, and that manage stormwater efficiently. But the urban forest is still a forest. It’s a community of living things, a habitat. And a large tree like a live oak is an ecosystem unto itself.

I’ve said that about a few plants, like milkweed, that are home to animal communities of plant consumers (monarch caterpillars, oleander aphids, milkweed bugs), and the predators that eat them (milkweed assassins, syrphid larvae, wasps). Live oaks, however, host their own plant communities as well.

Its combination of big, strong branches and a deeply furrowed bark invites a number of non-parasitic plants to rest on or take root on a live oak.

Spanish Moss

The first, and most famously associated with live oaks, is Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides). As I mentioned earlier, a sprawling live oak is an icon of the American southeast. That image is incomplete without, as historian Jonathan Lammers says, “Spanish moss hanging in the oh-so-perfectly artistic, Southern Gothic kind of way.”

Spanish moss is “an air plant, a bromeliad type plant that gets its nutrients from the air,” says Mindy. “So it’s not actually sinking roots into the tree and stealing nutrients or anything like that.”

It’s a plant that gets a bad rap. On a tree with weaker wood, it can accumulate and weaken limbs. It can become especially hazardous after a good rain, when the moss gets heavier. Spanish moss can also block out photosynthesizing leaves.

Many of us have an aversion to this plant because of its reputation as a stronghold for chiggers and other creepy-crawlies. Others dismiss this as nonsense. Doing a quick bit of internet research, you can see that this debate remains unsettled. One common theory is that chiggers enter Spanish moss once it falls to the ground. However, you can see in the video above that birds appear to be foraging in Spanish moss, and so there’s likely something living in there.

Resurrection Ferns

The other plant that predominates on the branches of live oaks is the resurrection fern (Pleopeltis polypodioides). They’re so named because they appear to die off in the winter, turning brown and shriveled. They’re adapted to do this when there’s not available water, as we saw during our recent drought. When they receive water again, they rehydrate and turn green.

None of this affects the live oak.

“They’re just kind of living on the bark,” Mindy says, a “symbiotic, friendly relationship.”

Lichen

The next plant we’ll cover is the embodiment of symbiosis. Lichens not only benefit from the space provided by the tree, but from a relationship with algae and fungi on the bark.

“The algae produces food for photosynthesis,” says Stan Rosenthal, “and the fungus helps it live better and collect nutrients better.”

Vines and other Plants

As it is with many trees in our area, live oaks can become wrapped in a number of different vines. Virginia creeper, smilax, poison ivy, all the usual suspects are represented.

What’s a little more unusual is that small trees or flowers are known to sprout from the crotch of the tree. Enough dirt might gather there to let a small root system establish itself.

Habitat for Animals

Walking through a park, you may notice birds or squirrels in the branches of a live oak. You may see a bird’s nest. When we visit the Tallahassee Museum, we spend time trying to spot bobcats and foxes lying inconspicuously on long live oak branches. It always makes me think about the animals I might be walking under when I’m out in the forest. The large structure of a live oak makes it an ideal shelter for these larger animals. To see the tree’s larger value to wildlife, though, we look a little closer.

Many of those birds are hunting for food. And live oaks are full of food.

“They also host 500-plus species of insect larvae, caterpillars, which are super-valuable to our songbirds that eat insects exclusively.” Mindy says. “In addition to being hosts to those animals themselves.”

Research has shown that the use of nonnative trees in urban environments has led to a decline in urban birds. The main reason is that a lot of insect larvae, in particular moth and butterfly caterpillars, have hosted on specific plants for thousands of years here. And caterpillars make up quite a lot of a songbird’s diet. As Apalachee Audubon president Peter Kleinhenz says, the seeds in our bird feeders are potato chips for the birds (though seeds are an important part of their diets in winter months, when insects are scarce).

They need those caterpillars. And quite a lot of caterpillars host on the Quercus genus.

A few common butterflies and moths that host on oak trees

With hundreds of caterpillar species hosting on oaks, it’s not realistic for me to create an exhaustive list here. And for the most part, they don’t host specifically on live oaks, so what I’ve put together here is a sampling of common species found on local oaks.

Flipping through my Butterflies of the Coastal Plain guide, I count four butterfly species that host on oaks in our area. Horace’s duskywing (pictured above), Juvenal’s duskywing, white hairstreak, and oak hairstreak. Consulting an IFAS page on butterfly larval food, I found two more: the banded hairstreak and sleepy duskywing. The photo above is from the Backyard Ecology section of this blog, where I write about the insects in my yard. This Horace’s duskywing may have hosted on the laurel oak in our front yard.

These two pink-striped oakworm moths were mating on a thistle below our laurel oak. The female likely flew up later to lay her eggs.

I saw these in Myers Park while walking with my wife. Another member of the Anisota genus.

I found this guy on my porch. Tussock moth caterpillars most commonly feed on oaks.

The most common caterpillar I saw while shooting video for this piece was a fall webworm moth. This is a generalist caterpillar, hosting on any of 100 or more tree or shrub species. They create webbed enclosures high in trees, which contain scores of caterpillars.

Oak galls

Since I started logging the insect life in my yard for the Backyard Ecology Blog, one of the most interesting forms of insect larvae I’ve encountered are oak galls. Most of them appear as strange lumps on oak leaf twigs, created by insects called gall wasps.

Oak gall.

Oak gall.

“Typically an insect will lay an egg on the oak twig, and it kind of grows wood around it.” Mindy says. “That’s the tree’s way of sealing off issues that it identifies as problems. That little bug matures inside the gall, and eventually comes out, usually no harm, no foul.”

When I started paying attention to the leaves on our laurel oak, I started to notice a variety of oak galls on leaves as well. These species make use of leaf tissue:

Oak leaf gall on live oak leaf.

Oak galls under a fallen laurel oak leaf.

I had originally thought that the image below was some type of caterpillar, and ventured a guess on the Backyard Blog. An entomologist commented that this was in fact an oak gall in the Andricus genus:

And then this year, I started finding translucent oak galls, the larvae of Amphibolips nubilipennis:

“Big Pools of Shade”

Storm resiliency, stormwater management, carbon storage, and habitat provision are all high value services. But the reason people plant and enjoy southern live oaks might be simpler than all of that.

“I’m just going to come back to Occam’s Razor, you know, the simplest answer is the easiest answer,” says Jonathan Lammers. “People like the big trees because it is hot here. And we see these big trees as forming big pools of cool shade.”

In technical terms, this is “reducing the heat island.” A live oak’s wide canopy can cover, and cool, a lot of ground, creating a microclimate. Stan pointed this out when we stood by that forested pond. The wet edge of the pond had originally excluded fire and allowed oaks to grow there. Now, the cooler ground temperature slows fire as well. A US Forest Service report shows us that this climate isn’t merely produced by shade. “The leaves are concave and, as litter, hold moisture to the ground. The moist environment discourages fire entry and keeps fire temperatures low.”

In a city, this microclimate can counteract the heat generated by paved surfaces reflecting the heat of the sun. Asphalt can be around 50º F hotter than air temperature, concrete about 25ºF, based on research by Frostburg State University used in this article on pavement and dog paws (I converted the temperatures from Celsius to Fahrenheit).

Tallahasseeans of the 1800s and early 1900s planted trees to shade their homes and yards, and to cool their livestock in pastures. As Jonathan points out, many of those homes are now gone, and many of those pastures have long since given way to neighborhoods, strip malls, and office parks. But a lot of that shade remains, and helps create local identity in the urban forest.

“And we see birds playing in them,” Jonathan says, “and we see squirrels running up and down them, and we see Spanish moss hanging in the oh-so-perfectly artistic, Southern Gothic kind of way. It’s a natural affinity.”