Tallahasseeans love their live oaks, and often when these trees are threatened by development, there’s resistance. We look at our relationship to this iconic southern tree, and how they have seen Tallahassee grow and change. Also, watch Part 2 of this story, in which we look at the live oak’s role in Tallahassee’s urban forest.

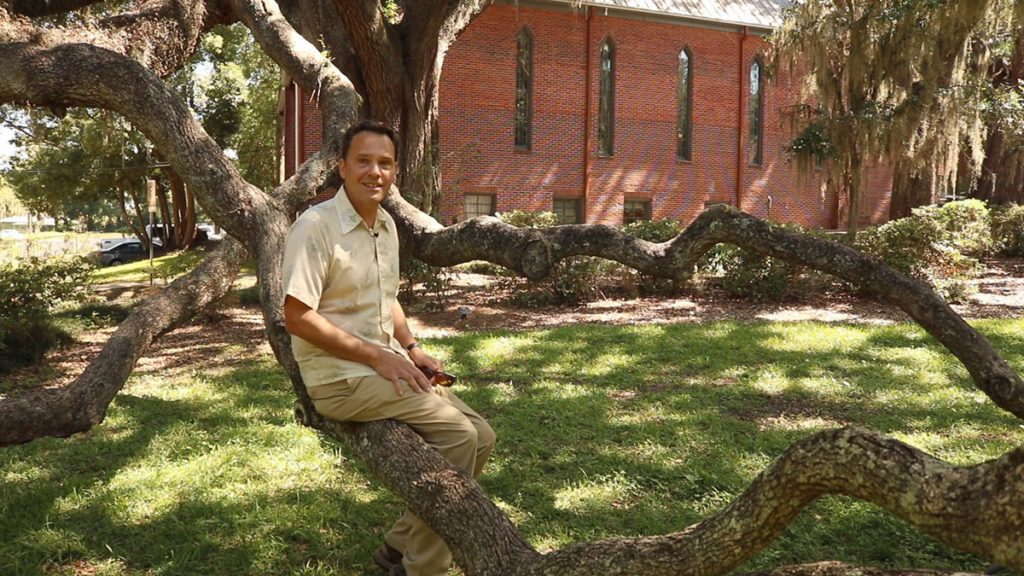

“So, why does Tallahassee have a love affair with live oaks?” asks Jonathan Lammers, a historian and advocate for historic buildings and heritage trees. He’s sitting on a long, winding live oak branch that touches the ground here in Cherokee Park. “I think most people, when they’re in the presence of a huge live oak, there’s a certain spiritual quality to it that you just can’t help but feel.

“They are magnificent and enormous living things. It’s like confronting a blue whale, except you get to do it on land.”

I’m guessing more of us have sat in the shade of one of these trees than have taken the time to really look at one. A mature southern live oak (Quercus virginiana) has a thick, dense trunk from which muscular branches arch out in every direction. If they have the space, and the humans who care for the tree don’t trim them, some branches will touch down and run along the ground, not unlike arms resting on a table; arms grown furry with resurrection ferns and Spanish moss, their trunks clothed in vines and lichens. Between the branches that touch down, and those that reach up and out, their canopy can cover 150 feet. Live oaks can appear quite stately, when they have space.

As Tallahassee has grown and expanded over the last century, we’ve often claimed their space for roads, condominiums, gas stations, and other construction. And when that happens, there are often residents there to protest it. A couple of weeks ago, a Blueprint Intergovernmental Agency meeting ran past midnight as dozens of people spoke on behalf of an oak. A petition to save the Benton Oak, as it is known, garnered over 35,000 signatures. In the end, though, none of that was enough to convince City and County commissioners to alter the rerouting of FAMU Way through the oak’s home in the Boynton Still neighborhood.

What’s the Worth of a Live Oak?

This wasn’t the first battle over live oaks in Tallahassee, and it’s not likely to be the last. In a way, it’s a battle over the identity of our city. Can we grow while preserving our natural feel, and our historic legacy? On the other hand, with such an expansive canopy over Tallahassee, do we need to keep every single tree in place?

And, if we can’t save them all, how do we decide which trees are worthy of preservation?

That’s really what we’re trying to get at with this two part look at live oaks in Tallahassee. In our next post and video, we’ll examine the ecological value of a live oak. As large, dense, long-lived trees, they’re superstars at supporting other plants and animals, storing carbon, resisting storms, and filtering water.

But they have a historic and cultural value as well, which is maybe not as easy to quantify. These are trees that can, potentially, be here long before you were born and live long after you are gone. We have oaks that were here at the founding of our city in 1824. And, as Jonathan shows us, they may outlive the buildings around them, and serve as historical markers for houses and neighborhoods that have faded into obscurity.

This story, today, is about our relationship with live oaks. Why did so many people plant them, and why do so many care so much when they’re threatened?

Live Oak Trail | Tree Preservation in the 1940s

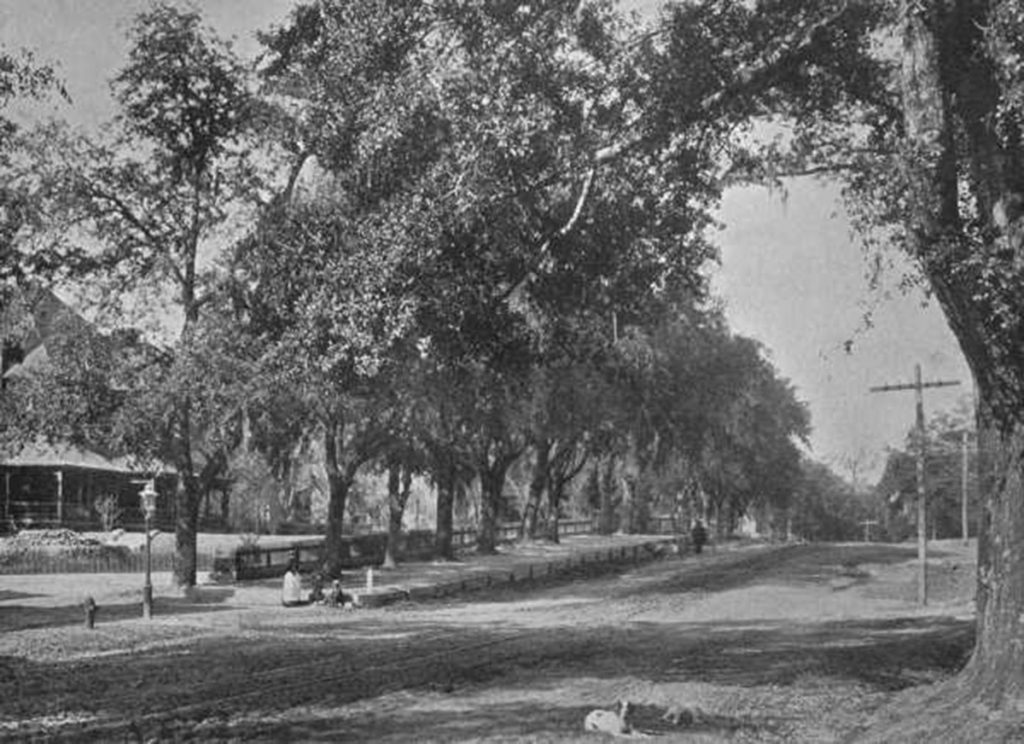

“If you look at pictures of north Monroe at the turn of the (twentieth) century,” Jonathan says, “it’s a canopy road… And the streets downtown, a lot of the roads weren’t even paved. Some of the live oaks stuck out into the street. And nobody really minded that, because they were all riding around town in their carriages, and the live oaks were shade.”

This all changed when cars came to Tallahassee. Wider, paved roads led to the cutting of live oaks. And, for the first time, the people of Tallahassee started considering how these sprawling trees fit into an increasingly urban landscape.

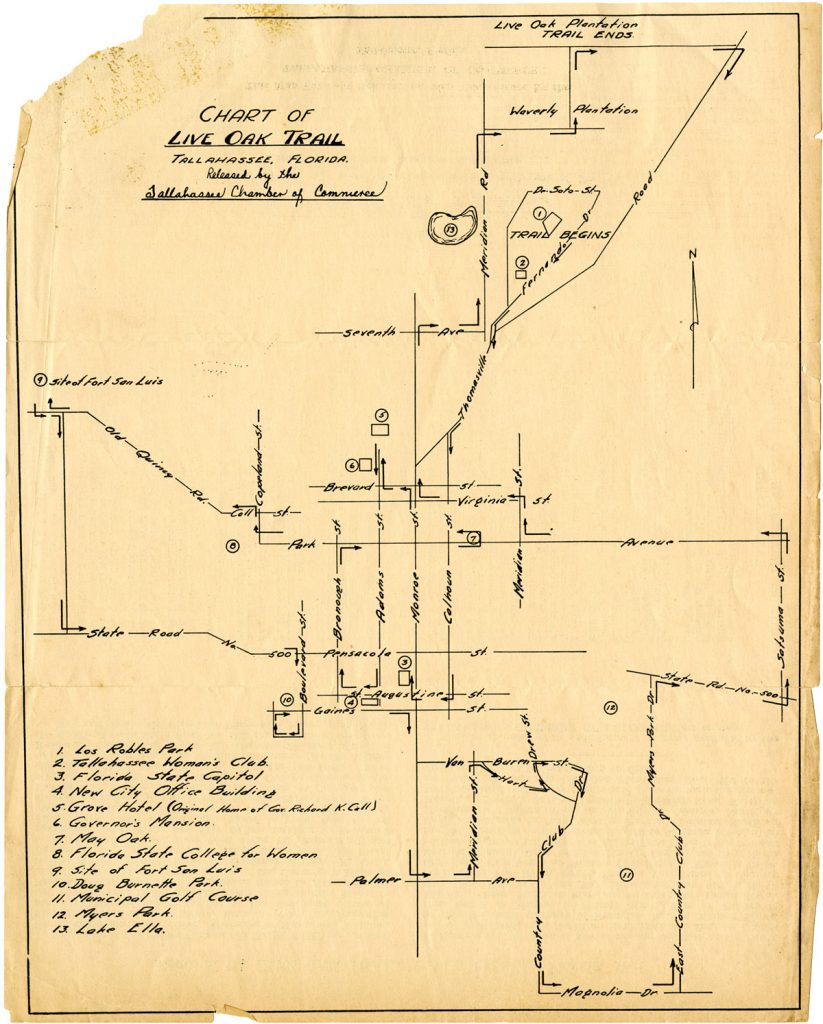

Leading the charge was Carrie Edwards Elliot. Carrie was married to Fred C. Elliot, the engineer who oversaw the draining of the Everglades to create farmland, and who designed the original layout of the golf course at the Capital City Country Club. Mobilizing the Tallahassee Garden Club, Carrie created the Live Oak Trail.

This driving trail started at Los Robles (Spanish for “the oaks”), and led to some of the more well known live oaks in town. It was a yearly event rather than a self guided tour, with 200 participants in its first year, 1940, as well as favorable coverage from the Daily Democrat.

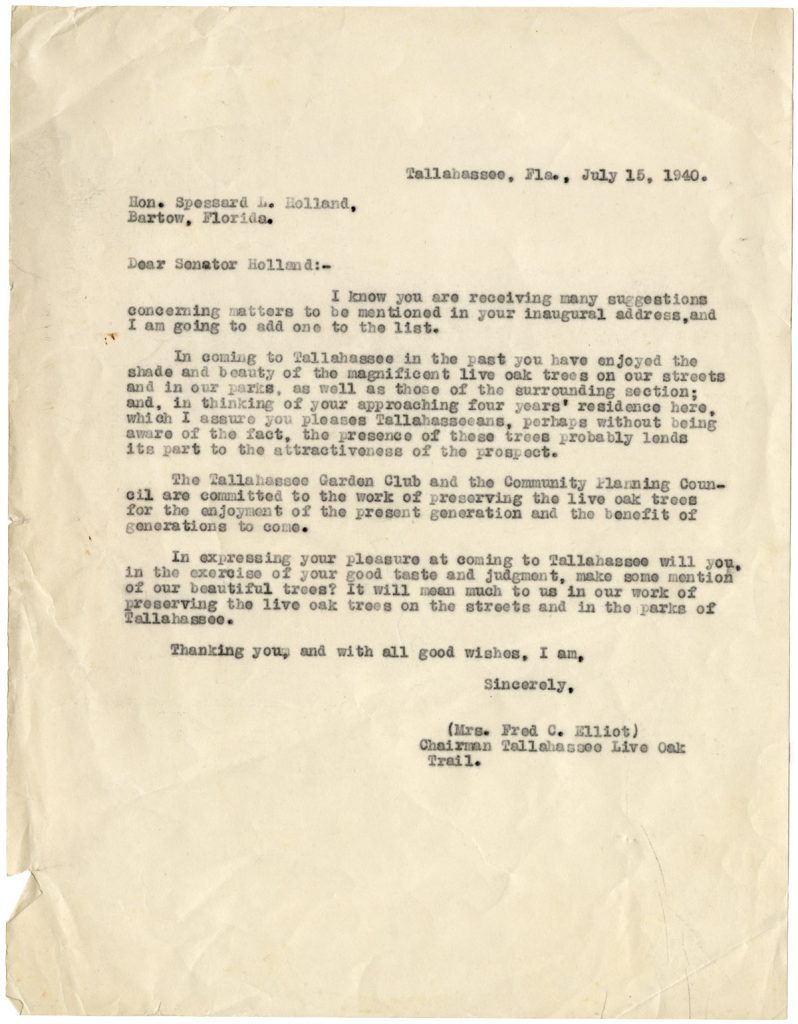

That summer, when Spessard Holland was elected governor of Florida, Carrie Elliot wrote to ask if he would mention live oaks in his inauguration speech.

“In expressing your pleasure at coming to Tallahassee will you, in the exercise of your good taste and judgement, make some mention of our beautiful trees? It will mean much to us in our work of preserving the live oak trees on the streets and in the parks of Tallahassee.”

Mrs. Fred C. Elliot, July 15, 1940.

The May Oak

Stop number seven on the tour was a large downtown oak in what is today the Chain of Parks. This popular gathering place was so beloved that even after the tree fell, its stump was commemorated with a plaque.

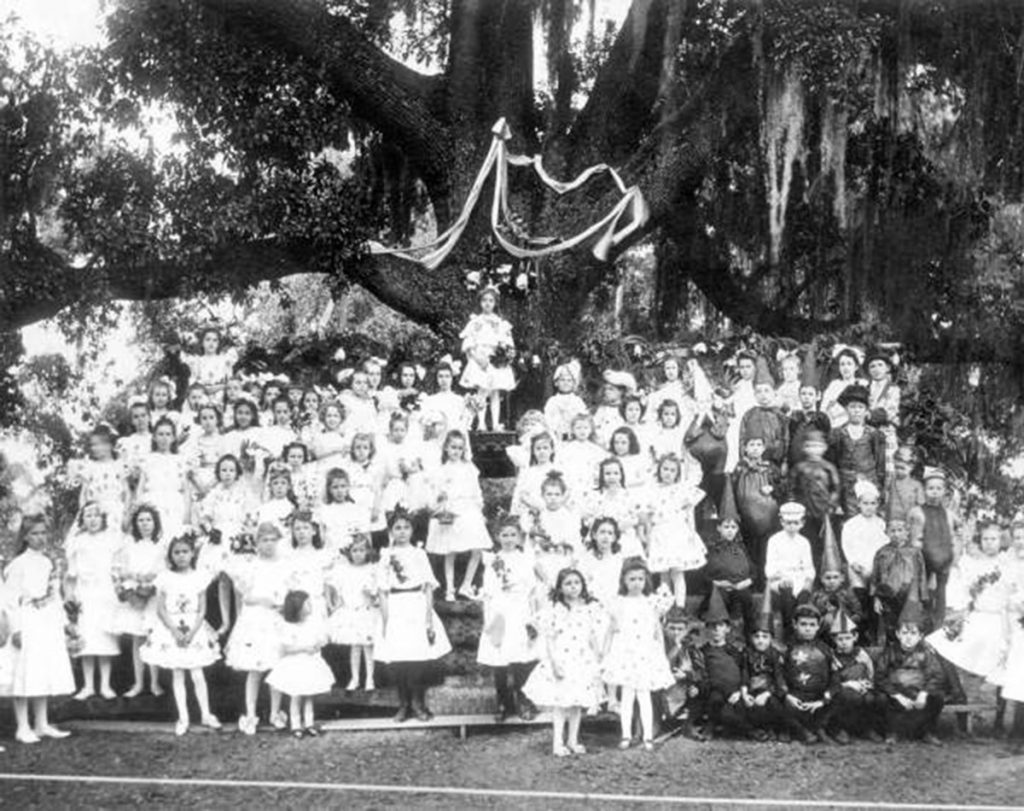

“The May Oak was a famous oak down at the eastern end of the Chain of Parks.” Jonathan says. “And it had an incredible spread. It became a really important spot for local gatherings, including a May Party every year, when a lot of the young ladies of the prominent families in town would dress up and gather underneath it.”

Take a look at how many well dressed people fit under the canopy of this tree:

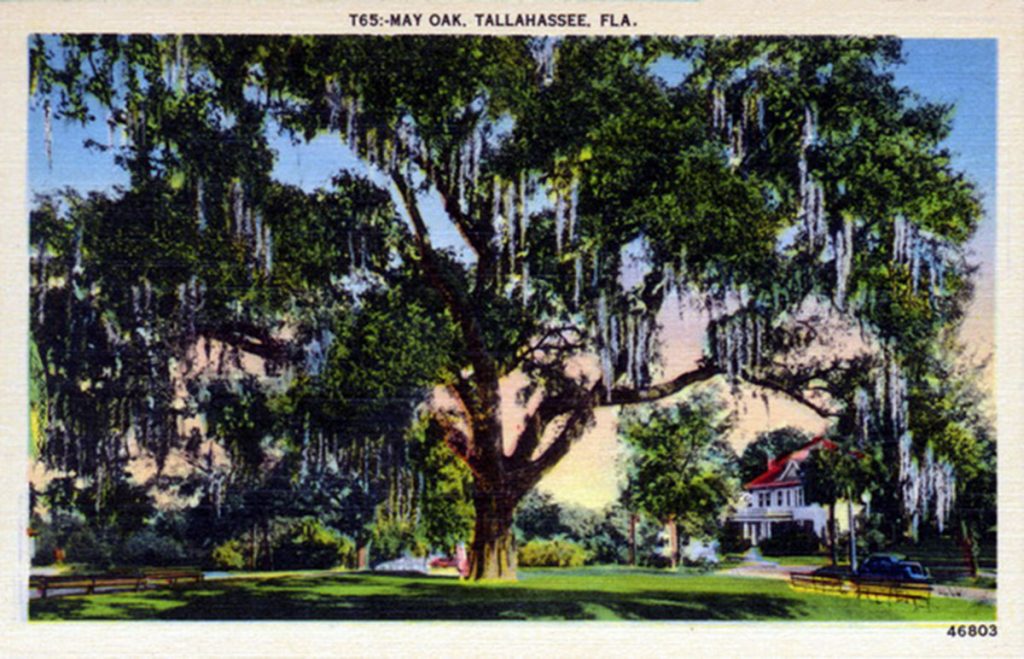

This postcard from 1940 claimed it was 1,000 years old (But was it? Read on):

The tree finally collapsed in 1986. As I said before, the stump remains, and children (at least mine) still play in it during downtown festivals.

Fighting for Trees

Though World War II put an end to the Live Oak Trail after two years, the Elliots and the Garden Club continued to fight the destruction of trees as Tallahassee expanded. As you can read in a Florida Memory Blog post on the trail, they had mixed success. “But, without the hard work of the Elliots, the Tallahassee Garden Club, and all of the other tree activists during the 1930s and 40s, there would be fewer trees today in the capital city.”

Tree preservationists in Tallahassee have continued this tradition of mixed success when it comes to protecting live oaks.

Concern for the cutting of trees in the 1980s led to the formation of a Canopy Roads Citizens Committee in 1990, and protections in the county ordinance for designated canopy roads. Currently, there are eight such roads in Leon County. Canopy Roads Overlay Districts, as protected zones are called, place several restrictions on “all lands within 100 feet from the centerlines of the roadways.”

Within the last couple of years, preservationists have had a tougher time protecting live oaks. You might have noticed the construction noises during Mindy Mohrman’s sound bytes. Excavators and bulldozers were moving red clay in a lot north of Cascades Park, where we shot the interview. There, last year, a grove of mature oaks was removed to prepare the site for the Cascades Project, which will line that side of the park with apartments and a Marriott Hotel.

In the wake of that removal, a group of citizens formed the Save Historic Structures, Heritage Trees Facebook group. The group has become a hub for coordinating protest, most notably at the Blueprint meeting we see towards the beginning of the video.

Boynton Still Oaks

Jonathan Lammers has been one of the more vocal detractors of Blueprint’s plan to move FAMU Way through Boynton Still, a small African American community. That’s his photo on the petition I mentioned earlier, to save the Benton Oak.

I was able to interview him at the site, which had once been a turpentine distillery, in July of 2019. Since then, the area has been closed off, and two of the oaks destroyed. We chatted in the shade of those trees.

“The two trees that we’re standing next to here are the shade trees for Shingles Chicken House, which was opened in the late 60s by an African American entrepreneur named Alvin Shingles.” Jonathan said, “He repurposed one of the distillery buildings and made it into a restaurant. And he made extremely delicious fried chicken. And people from all over Tallahassee, both white and black, would come to the restaurant, and it was a real anchor for the neighborhood until it closed about ten years ago.”

Jonathan sees a connection between the houses and trees on the site. “These trees, to me, are a cultural memory of the neighborhood, because the houses were built during a period when there wasn’t air conditioning.” Jonathan said, estimating the houses were built in the 1940s. “So the trees were really valuable… this was shade.”

He pointed out several mature pecan trees as well. “The mix of live oaks and pecans is sort of indicative of a point and time and culture in Tallahassee.” He listed the areas where you can still find this mixture: Levy Park, the Bond Neighborhood, Frenchtown.

Is the Benton Oak an “Exceptional Tree?”

The largest of the oaks was just down the street. It once sat in the backyard of Morris Benton, whose house had already been demolished when we visited. The petition to save the Benton Oak called for it to be protected as an Exceptional Specimen.

“That’s kind of a tree that’s above and beyond what you would expect as far as health, size, and just, general value to the site.” Says Mindy Mohrman, Tallahassee’s Urban Forester. With that designation, Tallahassee’s Environmental Land Use Code would protect the tree, and developers would have to redraw their plans around it. The petition claims that as a potentially 500 year old tree, the Benton Oak fits the definition.

So, is the Benton oak an Exceptional Specimen? Is it 500 years old? As we attempt to answer these questions, we can learn a lot about how trees are protected in Tallahassee.

How Old is the Benton Oak?

There is no precise way to measure the age of a live oak without cutting it down and counting its rings. But there is a way to get a general idea by measuring its trunk.

To learn a little bit about the process, I caught up with Stan Rosenthal and Sam Hand. Stan is our UF IFAS Extension’s Forestry Agent Emeritus, and Sam is an Associate Professor of Extension at FAMU. They have decades of forestry experience between them.

The first thing to take into account is the growth rate of a live oak.

“They do grow faster when they’re young.” Sam says. “Like we do. We grow up as juveniles, we hit a plateau. And then we begin maybe to expand. But we don’t get any taller. Well, that’s what live oaks do. They get up to about sixty feet tall, and then they begin to bulk up. And that’s a slow process.”

It takes between 50-75 years for a live oak to reach its mature height. After that, the trunk continues to gain girth, though not as fast as it had been. And the growth will depend on various environmental conditions from year to year, like temperature, or rainfall. And not every live oak grows in an equally suitable setting. If a live oak has more open space, it will grow out further than individuals crowded by other trees, or buildings. If sidewalks lay over their roots, or people park over their roots, that would inhibit growth as well.

So, with all of these variables, there’s no way to know the exact age of a tree short of knowing exactly when it was planted. But one man did provide a helpful way to approximate.

Patriarch Oaks | Tallahassee’s Founding Trees

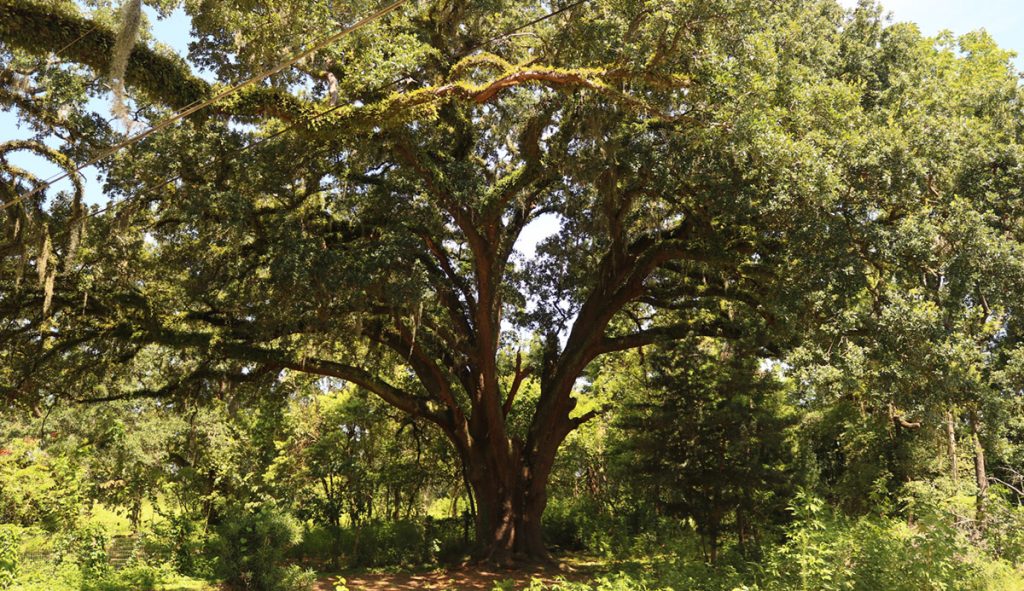

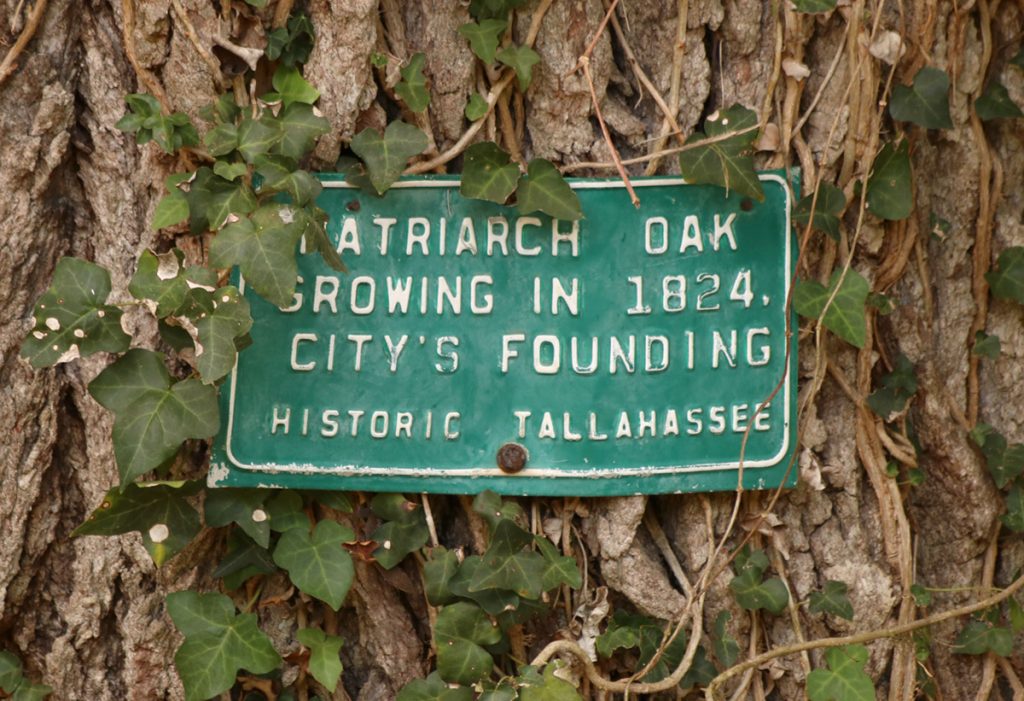

After finishing our interview at Boynton Still, we followed Jonathan Lammers to the Chain of Parks, and then to the Woodland Drives neighborhood. At Woodland Drives, we took a look at two large live oaks on Azalea drive. One was kind of lost in an overgrown space on the back side of an apartment complex. The other was across the street, towering majestically over a tidy lawn. This oak had a little green plaque on it, framed by vines.

This is a Patriarch Oak.

The Patriarch Oak program is a legacy of Clinton Huxley Coulter. Hux, as he was known, was Florida’s State Forester from 1945 to 1969. Governor Claude Kirk called him “the individual most responsible for the design and achievement of reforestation in Florida.”

“In the 60s,” Stan says, “when a tree got cut down in Tallahassee, in the downtown area, he would go and measure the stump and count the rings.” Hux produced a document with his findings. He determined that a live oak with a six foot diameter was about 150 years old, and would have been present at the founding of the city in 1824. in 1974, the Tallahassee Democrat used this metric to identify 66 patriarch oaks, which the Tallahassee Historic Preservation Board commemorated with plaques.

So these are the important numbers to remember when estimating the age of a live oak: a six foot diameter equals about a 150 year old tree.

For Comparison | Measuring the Lichgate Oak

I meet Stan and Sam at Lichgate on High Road. We walk down a short wooded path from the parking area, and as soon as we’re sight of the Lichgate Oak, Stan has a measuring tape in hand. They agree on a height to measure, and Stan circles the tree. If you look closely, you’ll notice the odd spacing on their measuring tape. Every increment is 3.14 inches, or pi. This saves them from having to divide the circumference of the tree by this amount to figure the diameter, which ends up being 84.7 inches.

They make a rough calculation by figuring our how much bigger it is than 6 feet. The Lichgate Oak is a foot longer in diameter than this, or about 15% bigger. This would make it 172 year old, but they round it up a little because live oak growth slows as it gets older.

“One hundred and seventy five years,” Stan says.

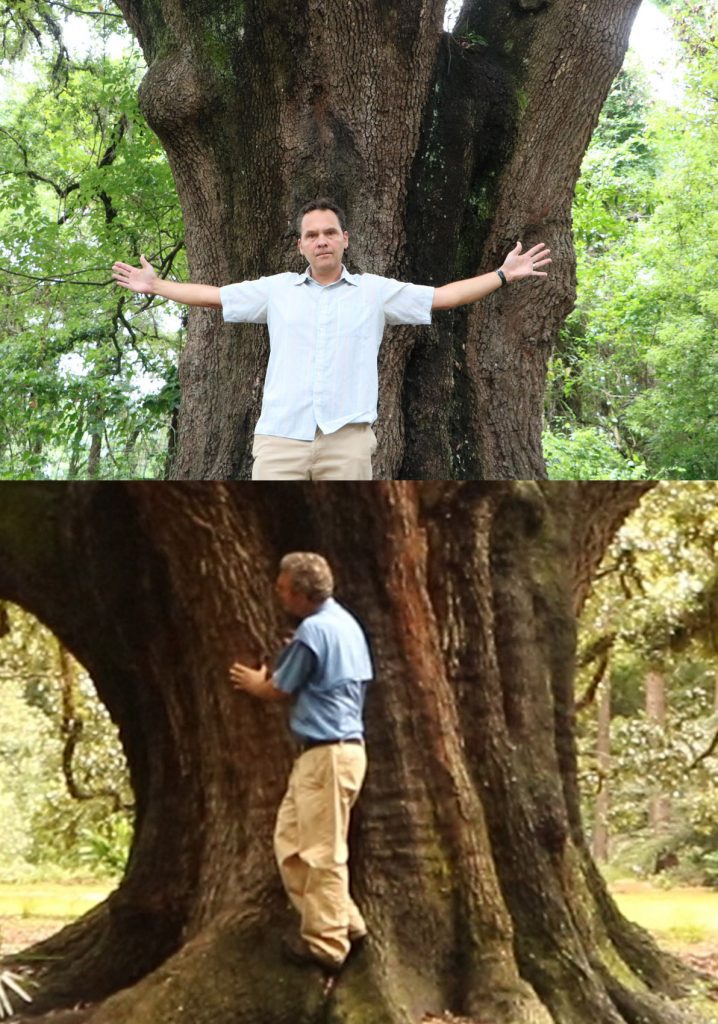

Sam and Stan had also measured the Benton and Shingles Oaks, and Sam points out how much smaller they are/ were than Lichgate. Here I’ve stacked photos of the Benton and Lichgate Oaks, and each with a person for scale. It should give you a rough idea of the difference.

“Those trees, I would say, are probably just in the range of 100-125 years at most.” Sam says of the Boynton Still oaks.

Defining an Exceptional Tree

So the Benton Oak’s is not 500 years old, but that doesn’t mean it’s not exceptional. And by exceptional, we’re talking about the definition outlined in the City’s Land Use Code:

Exceptional specimen means an individual tree which is in very good to good condition as evidenced by less than ten percent upper crown dieback, few epicormic branches, the absence of signs or symptoms of virulent disease, or other characteristics commonly employed to measure tree health; and exhibits characteristics of size, species, age, form, historical significance, or other qualities which make it of such greater value than individuals of the same species usually found in the city as to warrant special consideration as a biological and social resource to be preserved for the benefit of the general public. Determination to be made by director after consultation with the city forester in cases of doubt.

Tallahassee Land Development Code / Chapter 5 / Article I. / Section 5-12. Definitions

So, is the Benton Oak Historically Exceptional?

How would we go about rating its historical significance? We can start with its age, which Sam hand puts, at a maximum, at 125 years. It’s not 500, but 125 years is still a good amount of time. What would the tree have seen during its lifetime?

“When this tree started growing, it was the turn of the twentieth century.” said Jonathan Lammers during our July interview. “Tallahassee was a village of about three or four thousand people. This would have been the edge of town. We would have been surrounded by agricultural fields.”

Like the oaks and pecan trees at the Shingles site, this is indicative of a place and time in Tallahassee.

“When you start looking at where live oaks are, a lot of times they’re old pastures.” says Stan Rosenthal “People favored them.” Think of how hot it’s been lately, and think about being a cow in an open field. A large canopied tree would offer much needed shade, much as it would have to a house with no air conditioning. One forester measured it to be ten degrees cooler beneath the tree than in the sun beside it.

The Benton Oak was a pasture tree, then a backyard tree. It wasn’t in the yard of a prominent historic figure, or a major Tallahassee landmark. But it did see Tallahassee grow and change considerably over the last century. It was once at the edge of town; now it’s a fifteen minute bike ride from the Capital if you use the current FAMU Way trail.

But is that enough to be considered exceptional? The code, as it is written now, doesn’t offer any guidelines as to what makes a tree historically significant.

Protections for Trees in Tallahassee

Mindy Mohrman did determine that “Occupancy of the (Benton Oak) area should be prohibited” based on defects in the tree structure. The group fighting to protect the tree hired arborist Guy Meilleur, who concluded that the defects could be abated by installing structural enhancements, and that the tree overall was in good health. “Instead of reporting defensively by looking for ‘defects’,” Meilleur wrote, “arborists should be systematically assessing standard treatment options to abate risk.”

It can be argued that a tree that needs structural improvements doesn’t qualify as an Exceptional Specimen, based on the City Code. And aside from Exceptional Specimens and designated canopy roads, almost any tree can be cut with a permit.

“On any undeveloped site, any tree two inches and up is protected, and an applicant has to justify its removal” Mindy says. “As trees get larger and more valuable, there’s additional protections made on those trees, and an applicant has to go a little bit further in justification if they’d like to remove.”

The city also has a credit and debit system, where a tree can be removed if the landowner promises to plant a tree or trees of equal value. So, while every tree has some level of protection, very few have absolute protection.

For those who’d like to see more trees protected by the City Code, there is some hope. The city has prepared an Urban Forest Master Plan, which assessed Tallahassee’s tree canopy, and set goals for preservation. The plan is to then align development codes accordingly. Among the goals of the UFMP is to create a canopy with a high diversity of high quality trees.

And what is a high quality urban tree? Find out in Part 2 of this story.

Local Routes | Thursday, September 26 at 8 pm ET on WFSU-TV

The segment above is a taste of what’s to come on this Thursday’s Local Routes. In another story, WFSU-FM’s Gina Jordan explores a different aspect of the Boynton Still story we cover here- the destruction of African American neighborhoods in the name of Urban Renewal. Much as I used the conflict as a springboard to explore Tallahassee’s relationship with live oaks, Gina uses it to remember the destruction of the historic Smoky Hollow neighborhood and displacement of its residents.