Scroll down for some tips on raising milkweed from seed. In the video below, we learn about the Monarch-Milkweed Initiative at the St. Marks Refuge, and explore the habitats where we find native milkweeds. Also be sure to check out our other articles on raising monarch butterflies.

Gail Fishman points to a little green spot in the pine mulch. “That is a sprout of Asclepias humistrata.” The common name for this plant is sandhills milkweed, which is found in upland pine environments. We’re at the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge greenhouse, and the Monarch-Milkweed Initiative is planting seeds.

Seeing the little sprout, I get anxious- have I waited too long to plant my milkweed seeds? The answer is, no I haven’t, and it’s not too late for you, either. There are, of course, different procedures if you plant in winter vs. in the spring (and it has been a spring-ey February). And that’s why we’re here. The experts are going to tell us how to raise our milkweed.

Refuge ranger Scott Davis oversees the project. He has scoured the state’s swamps and forests in search of seeds belonging to our 21 native milkweed species. Within some regions, there are species only represented by about 20 individual plants. So it can take a bit of searching to find those seeds. That’s why, over two months last year, he drove over 7,000 miles to help fulfill this mission.

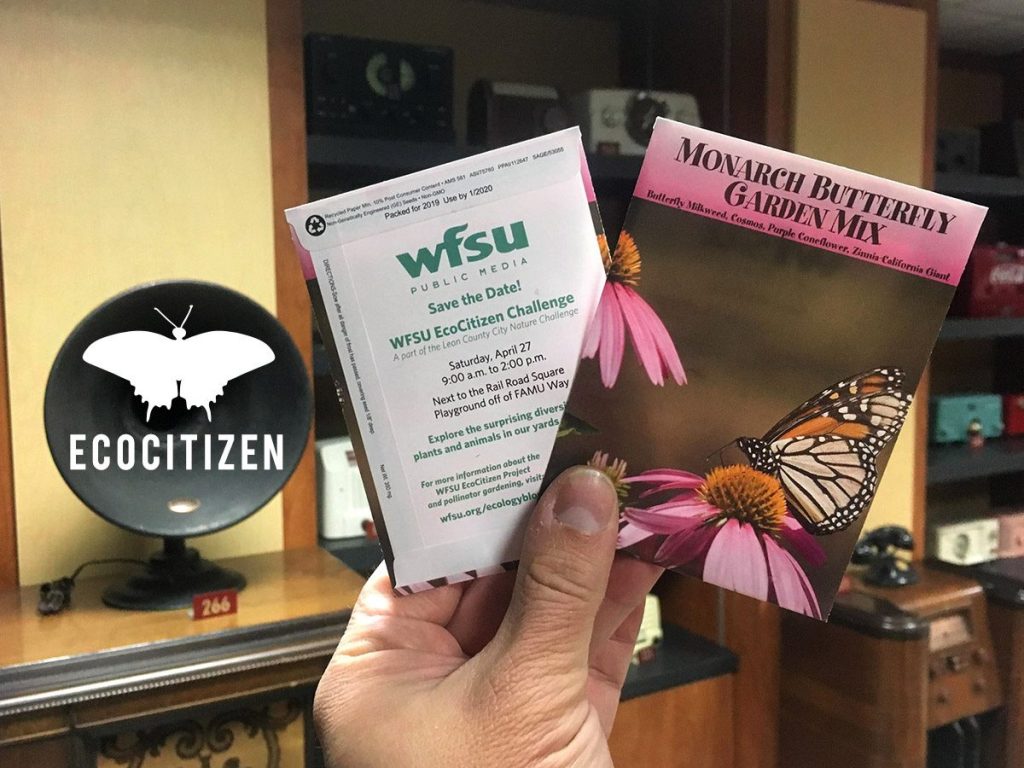

If anyone in this area knows milkweed, it’s Scott. So I ask him about the butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) seeds that WFSU has been giving out (This article was posted in spring of 2019- WFSU is not currently giving seeds away).

Tips for Raising Native Milkweed

Of Florida’s 21 native milkweed species, there are only a handful you can easily raise at home. We’ll talk about what it takes to grow those first- we know that’s why a lot of you clicked. We’ll also look at sandhills milkweed, which Scott calls the most important milkweed species in the southeast. After all, we garden with native species to restore some small semblance of the habitat we’ve built over. And different species have a different importance to monarchs as they pass through here.

Let’s start with the packets we’ve been giving out, which include butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa).

“The best thing to do when you purchase a packet of tuberosa seeds is assume that no seed prep has been done.” Scott says. So if you got seeds from us (and we have more), there’s a certain way Scott recommends you prepare the seeds.

1. Cold Stratification and Heat Shocking

“As soon as you buy your seeds, they should go directly inside your refrigerator,” says Scott. “Or, you need to put them in a bag, and put them somewhere dry on your porch.”

Like most native plants in our area, they need to go through something called cold stratification. If you’re out in the Apalachicola National Forest in December, you’ll notice a lot of dead-looking flowers. What you’re seeing is the last stage of a wildflower bloom- it has gone to seed. Native wildflowers seeds have evolved to germinate after sitting on the ground over the cold months, and activating once it gets warmer.

So here’s how cold stratify seeds:

- If it’s winter, and it looks like there’s cold ahead, leave the seeds on your porch as Scott describes. The warmth of your heated home won’t help stratify your seeds. The important thing is that seeds stay in temperatures of about 40 degrees for two weeks. Or-

- You may notice that it’s winter now, but it’s not staying at 40 degrees for more than a couple of days (and it seems to be warmer overall now). If that’s the case, place the seeds in the fridge for two weeks.

- After two weeks, heat shock your seeds. Scott says that the hottest water your faucet can produce is sufficient- 110 to 120º F. Place the seeds and the water in a bowl or a bucket and allow them to cool to room temperature.

- Let sit for 24- 36 hours.

The heat activates the seed, “and the water hits the living portion of the germ inside the seed, and then that’s the second condition to stimulate it to germinate.”

Planting and Watering Your Seeds

- Milkweed seeds (and most wildflower seeds), shouldn’t be planted any deeper than they are long. Oftentimes, people sprinkle wildflower seeds on bare dirt and rake it in. But Scott’s ideal is to push the seed in until it’s just beneath the surface (as we see Louie Sandstrum do in the video).

- “Keep it consistently moist, not wet.” Scott says. You’ll notice in the video that the Monarch-Milkweed Initiative was mulching their Asclepias humistrata with pine straw. As Gail Fishman explained to us, this keeps moisture in the soil around the seeds. And Asclepias tuberosa (like that in our seed packs) grows in a piney environment anyway, so you’re mimicking its natural setting.

Scott points out that milkweed has a high germination rate. And, as the name suggests, these are weeds. These are tough plants that will grow in a lot of places.

Asclepias perennis and the Early Monarch Surprise

Two other species of native milkweed I’ve been growing at home are aquatic milkweed (Asclepias perennis) and pink swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnta). Unlike the butterflyweed in the WFSU seed packets, which are from an upland plant, these other two are wetland residents.

Scott takes us down to the St. Marks Refuge visitor center to show us. Here, in mucky puddles formed by recent rains, are about fifty perennis plants. It’s February 8, still in the “dead of winter,” which can mean vastly different things in north Florida depending on what kind of year we’re having. He’s talking about the ecological importance of the plant: as the only native species that doesn’t lose its leaves in the winter, it’s the plant monarchs seek when they get here earlier in the year.

He doesn’t get too far into this explanation before he spots the first egg. And then another. These short, sparsely leafed plants are already hosting monarchs with over a month of winter left. At first, I’m excited. But then I start to wonder- is this enough for them to eat? Won’t they drown if they finish a plant and go in search of more leaves?

But Scott tells me that these leaves have several times more carbohydrates than many other milkweed species. They’re also more toxic, which is good for the milkweed tolerant monarch but less so for an animal trying to eat it or the plant. And, monarchs are known to make their chrysalis right on perennis, which, as it turns out, I have seen in my yard.

This is the right plant for the right time and place. The monarchs that came to Refuge could only have found these milkweed plants at this time of year, and they had everything the butterflies needed for their larvae.

And despite being found in swamps when in the wild, the wetland milkweed species we grow at home don’t have to be that much wetter than the more upland tuberosa.

“Tuberosa that you can put in your yard will tolerate very dry to moist conditions. But the aquatic milkweed and the pink swamp milkweed, both of those can tolerate moist to very wet conditions.”

Read More: Feeding caterpillars in your north Florida Garden

- Raising monarch, black swallowtail, giant swallowtail, and longtailed skipper butterflies, with photos of every life stage.

- Raising gulf fritillary caterpillars (passion flower caterpillars), with photos of every life stage.

- Caterpillar supermarkets: a list of the wildflowers and trees/ shrubs that host the most moth and butterfly caterpillar species.

- A lot of insects are out to kill your monarch caterpillars. It’s a sign that your garden is healthy.

Asclepias humistrata | “The most important milkweed in the southeastern United States“

There are milkweed varieties that won’t grow easily in the yard, but that are still critical species for monarch butterflies. One such plant is the one volunteers are planting in the Refuge greenhouse.

I first encountered sandhills milkweed (Ascelepias humistrata) in the Munson Sandhills region of the Apalachicola National Forest. It was late April, and Ryan Means was pointing it out to a group of Raa Middle School students on a field trip. That this plant was in full bloom at this time of year is important: it’s the reason Scott Davis calls this “probably the most important milkweed in the southeastern United States for monarch butterflies, because it emerges around that time of the year, in May, when the monarchs are beginning to return to this region.”

We see that Asclepias perennis has leaves all year round, so there’s larval food for the early-arriving monarchs. And humistrata is ready when the migration really gets going in May. The other species offer leaves and flowers at different times, and grow in varied habitat types.

And that last point is key. Monarchs make a multi-generational migration from Mexico to southern Canada. Every few weeks, they’ll need to lay eggs and get that next generation going. While other butterfly species spend their lives within a couple of miles of where they hatched as an egg, monarchs need to find larval food in a variety of places, and in a variety of ecosystems.

Affected by a Lack of Fire

Scott takes us to some burn plots near the Refuge visitor center. Much like the Tall Timbers plots started by Herbert Stoddard decades ago, they illustrate what a pine forest looks like when it is burned every year, two years, three years, or not at all. We’re standing next to a frequently burned plot, an open understory filled with grasses and palmettos.

“From here down to there, you can find five different milkweed species growing.” Scott says. They’re dormant now, as are most of the wildflowers that will start popping out soon. All of the varieties of the longleaf pine habitat rely on fire to clear woody growth in the spaces between pine trees, allowing a high diversity of grasses, flowers, and succulent plants to thrive. These, in turn, support a high diversity of animal life.

Unfortunately, it’s a habitat that’s taken a hit after a couple of hundred years of logging and development. And while habitat loss affects many types of ecosystems, existing longleaf forests face an additional problem. Not all of them are burned as frequently as they should be.

“And so that natural community that these milkweed need, it disappears.” This affects milkweed as well as a host of other plants and animals. As Scott tells us, “We maintain the site for the milkweed. We maintain the site for all species that also live in that landscape. So the frosted flatwoods salamander, the red cockaded woodpecker, the gopher tortoises, all of the rare plants and rare animals all depend on fire.

“So that’s why I typically tell people, ‘If you manage for the milkweed, you manage for everything else in the landscape.'”

Aquatic and Tropical Milkweed

Let’s go back to the scene I describe above, where we find monarch eggs by the Refuge visitor center. I had just seen photos of the monarchs’ overwintering grounds in Mexico, oyamel trees covered in orange and black butterfly wings. After all, we still have over a month of winter left. So I asked Scott, is the monarch that laid these eggs an early migrator or part of a population that has been taking up year-round residence in Florida?

“This plant (Asclepias perennis) is implicated in a lot of arguments for monarchs not migrating, or rather migrating less and less because of climate change, because this plant is evergreen and available all year long. Surveys over the last few years have shown that more and more monarchs are not leaving the region. They’re staying.”

One reason is that we’ve been having warmer winters. And because this particular kind of milkweed has leaves throughout the winter, monarchs have started laying eggs on them later and later in the year.

To a lot of people, the main culprit for this behavior has been non-native tropical milkweed, Asclepias currassavica. It’s also an evergreen, and for a long time was the most widely available milkweed in nurseries. That’s one reason we’re told to cut the plant back in the winter, to prevent monarchs from wanting to stick around.

But Scott doesn’t buy that, because native perennis plants have the same results.

“The reason that you should cut back the (non-native) milkweed is not because it’s causing a (disruption to) the migratory population,” Scott says. Its invasive nature and the fact that it can spread OE (Ophryocystis elektroscirrha, which is lethal to monarchs) are the reasons you should cut it back, Scott says.

Right now, the Monarch-Milkweed Initiative is aiding in a study comparing monarch and queen butterfly larvae on aquatic and tropical milkweeds. They want to know if these butterflies have a preference for one over the other, and are comparing survival rates for caterpillars on both plants.

If you’re interested in helping monarchs in the area, you can volunteer to help the Monarch-Milkweed Initiative. They’re most active earlier in the year, when it’s time to plant milkweed. Later in the year, volunteers can help with the Refuge’s Monarch Tagging program, which we covered a couple of years ago.

Dig Deeper into Backyard Ecology

What can we do to invite butterflies, birds, and other wildlife into our yards? And what about the flora and fauna that makes its way into our yards; the weeds, insects, and other critters that create the home ecosystem? WFSU Ecology Blog takes a closer look.