In January 2026, we might see oyster boats working in Apalachicola Bay for the first time in five years. Might. Oyster bars will have had five years to reestablish themselves, to build reef structures without oyster tongs tugging at them. Will that be enough time for the reefs to fully regrow, and once more sustain a fishery? And, if not, will the harvest resume anyway?

During the closure, researchers, government agency representatives, nonprofits, and community members have been working to ensure that when the bay opens, it can stay open and productive in a way it hasn’t been since the fishery crashed in 2012. After years of experiments and discussion, they now have “The Plan.”

“What it is is a list of options and recommendations to government entities, that have a consensus of stakeholder agreement,” says Dr. Sandra Brooke. Dr. Brooke is a senior researcher at the Florida State University Coastal and Marine Laboratory. She is also the principal investigator of the Apalachicola Bay System Initiative (ABSI).

When the time comes, it falls to Florida Fish and Wildlife to manage the fishery. This includes decisions about when to close all or part of the bay to harvesting, limits on harvesting, and how to enforce their rules.

“The Plan” is an attempt to guide the management of the oyster fishery using what ABSI has determined to be the best scientific practices, and with community buy-in. Since none of the environmental factors that contributed to the collapse have changed, ABSI hopes their recommendations can help the fishery adapt to drought and water management upstream of the Apalachicola River.

Read the full Apalachicola Bay System Ecosystem-Based Adaptive Restoration and Management Plan.

Addressing diminishing freshwater flows

The recommendations presented by ABSI and their Community Advisory Board are rooted in the potential causes of the oyster fishery crash. I say “potential” because no research inquiry has determined the exact cause of the crash. This was due largely to a lack of in-depth monitoring prior to 2012, a deficiency ABSI addresses in “The Plan.”

One factor decades in the making was freshwater input from the Apalachicola River. When the fishery crashed in 2012, the river had been in drought operations for several months, and for the third time since 2007. The Apalachicola is managed together with the Flint and Chattahoochee Rivers in Georgia. The two Georgia rivers flow through a system of dams and reservoirs overseen by the Army Corps of Engineers (ACE). The final dam is the Jim Woodruff Dam, located where the Flint and Chattahoochee meet to form the Apalachicola. Through the Woodruff Dam, the Corps directly controls the amount of water that flows into the river.

The Apalachicola is Florida’s largest river in terms of volume, flowing 106 miles from the Georgia border and into Apalachicola Bay. When Georgia experiences drought, the ACE holds water back so that it can be used by farms along the Flint River and by cities and towns, including Atlanta, along the Chattahoochee. During drought operations, the Woodruff Dam outputs an average of 5,000 cubic feet per second, the lowest allowed by law.

When freshwater flow remains low for an extended period, salinity increases in the bay. This creates conditions favorable for oyster predators, snails such as oyster drills and crown conchs, who reproduce at a higher rate in the saltier water.

Suing for water

In 2013, Florida sued the state of Georgia, claiming that Georgia’s irresponsible use of water led to the fishery crash. The Army Corps of Engineers, not Georgia, manages the water based on rules set forth by the U.S. Congress. However, Florida contended that if Georgia had used water more responsibly, there would have been enough to keep the Corps from enacting drought operations.

The U.S. Supreme Court was not convinced. Their ruling stated:

“Florida’s own documents and witnesses reveal that Florida allowed unprecedented levels of oyster harvesting in the years leading to the collapse. And the record points to other potentially relevant factors, including actions of the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, multiyear droughts, and changing rainfall patterns. The precise causes of the Bay’s oyster collapse remain a subject of scientific debate, but the record evidence establishes at most that increased salinity and predation contributed to the collapse of Florida’s fisheries, not that Georgia’s overconsumption caused the increased salinity and predation. Florida fails to establish that Georgia’s overconsumption was a substantial factor contributing to its injury, much less the sole cause,”

Supreme court of the united states (Florida v. Georgia ruling)

Increased salinity and predation are listed as contributing factors, but so is a high level of oyster harvesting. During oral arguments, one justice referred to a report that the floor of the bay looked like a “gravel parking lot.” You can see this in a January 2013 Ecology Blog video. When oysters die, their shells persist, as does the oyster reef structure. Apalachicola reefs had been broken apart and oysters were removed.

Apalachicola Bay had been a resilient ecosystem. Oysters reach maturity faster than in other estuaries and had always regrown quickly after intense harvesting.

But it might not be realistic to expect the bay to be as productive as it was before 2012. The challenge is to find the best way to manage a resource still on the mend.

Apalachicola Oyster Fishery Timeline

- May – December 2007: The Army Corps of Engineers enacts drought operations for the ACF Basin. During drought operations, the ACE releases a daily minimum of ~5,000 cubic feet per second into the Apalachicola River.

- April 20, 2010: The Deepwater Horizon oil platform explodes, sending 4 million barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. While large oil mats do not reach Apalachicola Bay, fishery closures across the Gulf increase demand for Apalachicola oysters.

- May – December 2011: Drought operations intermittently enacted.

- May 2012 – January 2013: Drought operations. In 2012, the Apalachicola River experienced its lowest-ever recorded river flows.

- September 2012: Winter oyster bars open for harvest, but oyster bars have not grown back from the previous season. Florida Governor Rick Scott asks the U.S. Department of Commerce to declare a fishery disaster.

- August 12, 2013: U.S. Secretary of Commerce Penny Pritzker declares a commercial fishery disaster in Apalachicola Bay.

- August 13, 2013: Governor Scott announces Florida will sue the state of Georgia over their use of water upstream of the Apalachicola River, in Georgia’s Chattahoochee and Flint Rivers.

- December 2020: The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission imposes a five-year moratorium on harvesting oysters in Apalachicola Bay.

- February 21, 2021: The U.S. Supreme Court hears oral arguments in the case of Florida v. Georgia.

- April 1, 2021: The Supreme Court rules in favor of Georgia, stating that, while salinity and predation were factors in the collapse, Florida could not prove that Georgia’s water consumption caused the increased salinity and predation.

- December 2025: The moratorium on wild oyster harvest in Apalachicola Bay is scheduled to end.

Now that we’ve reviewed the challenges facing the bay, let’s dig into ABSI’s recommendations to meet those challenges.

Goal A: A Healthy and Productive Bay Ecosystem

This goal deals with habitat restoration and developing a set of measurable indicators of oyster reef health.

Not long after the system crashed, the state of Florida started dumping oyster shells in the bay, a process known as cultching. Oysters need a hard surface on which to grow, and when oyster larvae swim in the water column as plankton, they seek out other oysters to attach to their shells. Laying shell on the muddy bottom of the bay was supposed to give those larvae, known as spat, a place to land.

Placing loose shells directly on mud did not work.

“The trouble is, when you put that thin layer of material on top of an unstable substrate, it gets moved around and buried,” Says Dr. Brooke. “And it gets away, especially in Apalachicola, which is like an angry washing machine. It’s just currents all over the place.”

After the bay closed, ABSI tested multiple materials to see which best stabilized the bay floor, trying oyster shell, fossilized oyster shell, and limestone rock. Limestone is often made of calcium carbonate, the same material as oyster shells. This is because limestone forms from oysters and other marine organisms over geologic time.

ABSI found that larger chunks of limestone worked best. A large rock provides more surface for a spat to settle on and is harder to move around. Another benefit is that oyster tongs are less likely to damage large rocks. After their success with limestone, ABSI tried concrete and found it worked about as well.

How do we know an oyster reef is healthy?

Say the state allocates funding to lay rocks on oyster bars. They consult with oystermen to find the spots that had once been the most productive. Over time, spat settles on the rocks, and oysters grow. New oysters then grow on those oysters, and they form a reef. At what point can the people managing the bay say the restoration was successful?

Part of Goal A is to establish how to measure the health of an oyster reef. One way to do this is to get eyes on the habitat. Commercial oyster reefs in Apalachicola Bay are subtidal, meaning they are always submerged. If a scuba diver heads down to the bay floor, what do they look for? They might count oysters within a one-meter quadrat, both market-sized adults and the generation coming up to replace them. A key indicator of reef health is the number of spat that settle there; if they aren’t settling, new oysters won’t grow. Also while on the bottom, a diver can look for any other concerning signs, such as an increase in oyster predators.

“The Plan” recommends rapid ‘spot-checks’ where oystermen bring up sections of reef to get a quick sense of the health at any point in the bay.

Oyster predators are affected by the salinity of the water. If Florida Fish and Wildlife tracks salinity over time, they might predict when oyster drills would stress oysters, and decide to close the bars. They could also correlate salinity with freshwater discharge from the Woodruff Dam. “The Plan” also recommends looking at nutrients, temperature, pH, and other water quality metrics.

All of this information could be used to guide the management of the bay.

Goal B — Prioritized Strategies for Sustainable Management of Oyster Resources

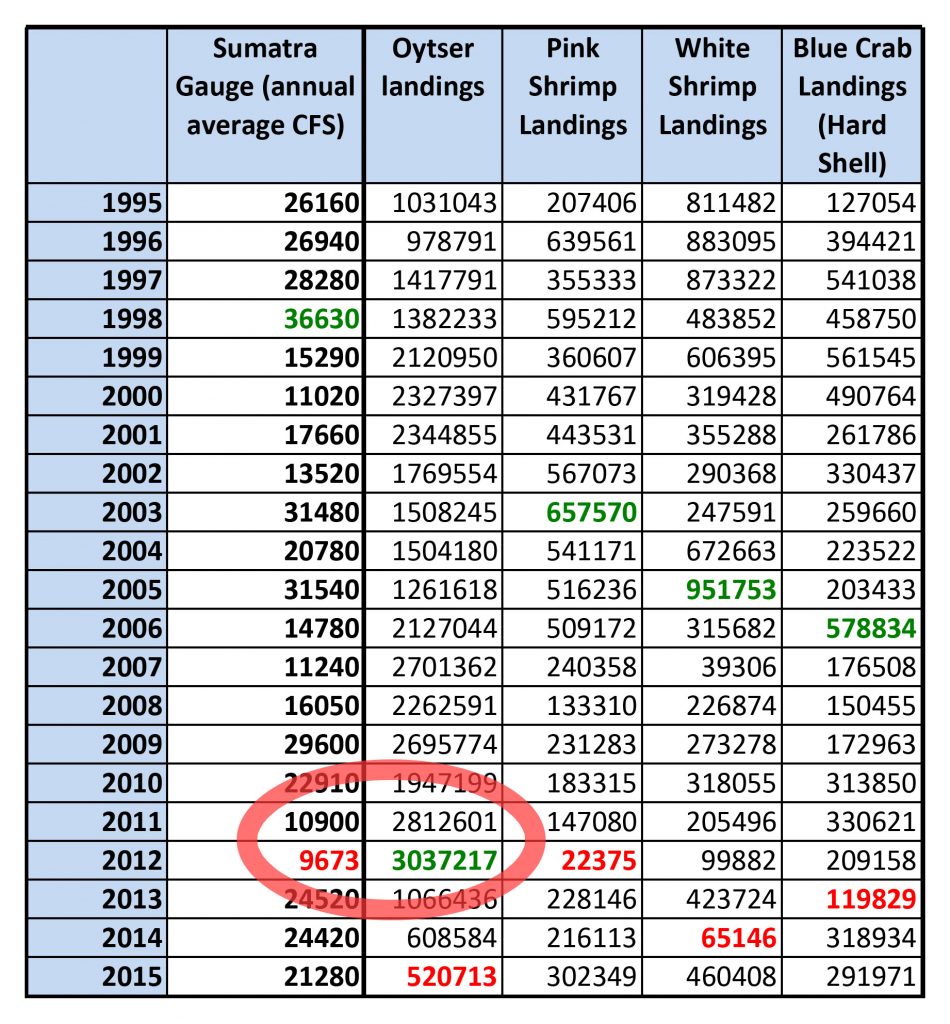

While 2012 was the year the Apalachicola Bay oyster fishery collapsed, it was also the year with its highest-recorded oyster harvest. When the winter bars opened in September, the Apalachicola River had been in drought operations for four months. By the time 2012 ended, it had recorded the lowest flows in the river’s history. The second-lowest flow was in 2011, the year with the second-highest landings, or oysters brought to the dock.

At the time, Florida did not close the bay based on environmental factors. “The management of the oyster fishery in Florida wasn’t particularly sophisticated,” says Dr. Brooke.

“The Plan” makes a case for adaptive management. Depending on conditions before the harvest season starts, FWC could decide to not open the bay or to adjust daily limits. If conditions change during the season, FWC could again adjust bag limits or close the bay, or parts of the bay that are struggling.

Other recommendations would limit when and how many oysters a person could harvest. This includes doing away with harvesting over the summer, when oysters spawn. Oysters are less tasty when spawning, and leaving them alone in the summer would increase the number of oysters trying to make new oysters. Another recommendation would include daily limits during a five-day harvest week, and limitations on recreational harvest.

These guidelines put the burden of sustainability, in part, on Apalachicola oystermen. It’s a burden they would share with FWC, who would have to enforce limits and closures.

Policing the oyster harvest

Sandra Brooke says that with all the limits and emphasis on enforcement, buy-in from the commercial fishing community is critical.

“If a management agency comes up with regulations that the community absolutely doesn’t agree with, they will violate them,” she says. “I mean, there’s not enough cops out there to keep people from breaking the law if they don’t agree with the law.”

One law enforcement model she thinks would work in Apalachicola Bay is the one in place in Alabama.

“They need check stations, or daily checks like Alabama does,” says Brooke. “You have to leave your license when you come in, and in order to get your license back… they check your catch. And then they go out on boats to the different places where people are harvesting.”

Traditionally, Apalachicola oystermen have not been heavily regulated. Dr. Brooke said this created friction with a few of the seafood industry representatives on the ABSI Community Advisory Board. While it may have caused a few seafood workers to leave the council, many remained involved and will be involved with the community group that will work to advance the plan, the Partnership for a Resilient Apalachicola Bay.

Goals C, D, and E: Community buy-in and a thriving oyster economy

“The Partnership” won’t be affiliated with FSU, FWC, or any other large organization. It is meant to be the community’s means of advocating for and stewarding Apalachicola Bay. Dr. Brooke hopes that as an independent entity, members of the commercial seafood community will be invested in it.

Community buy-in is as much a part of the Plan as the strategies to protect the oyster population. Goal C sets up the Partnership for a Resilient Apalachicola Bay. Goal D looks to engage community stakeholders and create education programs for schools and adults.

The final goal is a “Thriving Economy Connected to a Restored Apalachicola Bay System.” Every goal and recommendation was crafted in service of this overarching goal. For decades, the seafood industry was the primary driver of Franklin County’s economy. ABSI’s goal is for this to be true again by 2030.

There’s no way to know whether the plan will work without implementing it. There’s also no guarantee that Florida Fish and Wildlife will adopt it.

Maybe the individual management options are not as important as the involvement of those whom the plan would affect most. This may be the most ambitious aspect of the plan, the creation of a new normal. Oystermen committing to monitoring the bay, and accepting farm-raised oysters as a supplement to the wild harvest (a Goal E recommendation). Allowing the bay to sometimes close in the short term in the hopes that the resource thrives in the long term. Changing expectations mid-season based on conditions.

The state or the stakeholders might adopt all or none of the recommendations. What ABSI is telling us is that they’re better off figuring out together than apart.