Your mission over the next few weeks: roam Florida’s sandhills and scrub, and photograph everything that blooms or flies. The researchers who need these photos are looking for specific species, but while you’re out there, why not get it all? The sandhills and ridges in our state are biodiversity hotspots. They are ancient coastlines and one-time beach dunes, home to more than a few specialized and endemic species. I’m often surprised by which of my iNaturalist observations turn out to be “species of interest.”

We know iNaturalist as a handy app that tells us what plants and animals we see on hikes, or in the garden. I’ve written a bit about it as a gardening tool that lets us know which weeds are native, nonnative, or invasive. And I love learning about the (almost) endlessly diverse insects in my yard or in the forest.

If you’ve never used iNaturalist, this is how it works. You upload photos of a plant, animal, fungi, lichen- anything alive. The app scans the images and makes suggestions based on the organism’s appearance, and what species resemble it in your area. Other users check your identification and either verify it or suggest something new.

Many of the people looking over your observations are biologists, and sometimes the reason they are looking at your photos is that they are studying that thing you photographed. I’ve been contacting some of these researchers to learn how they use the data we collect. In doing so, I’ve found a few fun plants and critters we can start looking for soon here in Florida.

Ride your bike, take a hike, and maybe find a rare bee

Sandhills are not only places to find rare and endemic plants and animals, but they are also some of our area’s great outdoor playgrounds. Just south of Tallahassee lies the Munson Sandhills region of the Apalachicola National Forest. Cyclists know it for its mountain bike trails, which connect to the St. Marks Historic Railroad Trail. You could ride your bike to the Munson Sandhills from Cascades Park on a paved trail. Some of the Munson trails are also open to equestrians, and they all make for a nice hike. Throughout the panhandle, sandhill habitat is protected in State Parks and other preserves you can visit recreationally.

When you’re working up a sweat on the trails, you’re roaming a landscape that had once been more extensive. It’s a fragmented habitat compared to what it had been. Populations of sandhill plants and animals have become isolated from each other, and are sometimes pretty small. A smaller population is a vulnerable population, especially when the species is adapted to so specific a setting.

The soil here is pure sand, and it drains quickly. Because the sand is deep beneath hills, a multitude of animals burrow into it to escape the heat or cold, nest, or shelter from fire. Fire is the driver of biodiversity in sandhills, killing back woody plants growing in the filtered light of longleaf pine needles. With regular fire, turkey oaks, blueberries, and other hardwoods stay shrub-sized. This, in turn, leaves space for grasses and wildflowers, and for the animals that forage amongst them.

The early bees, butterflies, and wildflowers of north Florida

As winter turns to spring, I’m interested in those early-blooming plants and the pollinators who visit them. In my yard, blueberry digger bees only fly when blueberry shrubs have flowers. They take pollen and nectar from their namesake plant as well as other early spring flowers such as redbuds and Florida betony. Blueberry flowers and digger bees are gone by the end of April. Compare them to common eastern bumblebees, who fly from spring through December and visit almost every type of flower.

Consider the insect that needs areas of open sand for nesting, and which has a specialized relationship with a plant that blooms for a short time at a specific time of year. It is an animal for its place and time. If you go to that place at the right time, maybe you see a frosted elfin or sandhills cellophane bee. There is no guarantee. There are few places in our area where those animals have been seen, but you can help change that.

The following are sandhill and scrub (a related habitat found in central Florida and on the coasts) species you can seek out and iNaturalize. I’ll share the likely conditions for each, and, for the insects, the plants they associate with. Again, no guarantees. Part of the fun is the search, and in an environment such as this, you might something cool that has nothing to do with the animal you seek.

The sandhills cellophane bee – a species described in 2016

Colletes ultravalidus was first found by a biologist working for the Florida Natural Areas Inventory, Paul Russo, who reported it to Dr. John Ascher. Anyone who has uploaded bee photos to iNaturalist or Bugguide knows Dr. Ascher, who specializes in bees and bee data. He has compiled a database of all known bees on Earth and has checked thousands of bee observations for accuracy. He has on a couple occasions let me know that a bee I photographed was something special. Dr. Ascher described the sandhills cellophane bee in 2016.

It’s a relatively new bee, to human observers. The more we can photograph and (hopefully) video it, and the more places we find it, the more researchers can learn about it.

So, what do they already know? Colletes ultravalidus has been found in sandhills near cypress wetlands. Here is where we find climbing fetterbush, a vine related to blueberries. In the specimens Dr. Ascher examined, 97% of the pollen on the bees came from the heath family, which includes fetterbush and blueberries. The two observations of this bee in Leon County show it on blueberry flowers. However, another iNat observation near the Suwannee River, made after the species was described, shows one on cherry flowers.

Dave Almquist, another FNAI biologist, found the first known nesting sites for the Colletes ultravalidus. They enter their nests through small mounds on open areas of sand. If you see the bee, an important feature that distinguishes it from other cellophane bees is its face.

Sandhills, near wetlands, blueberries or fetterbush, and open sandy areas. Go!

Looking for one rare bee, you may find others

The two sandhills cellophane observations in Leon County were made at Leon Sinks, just off the trail. The Munson Sandhills lack cypress wetlands, but there are a few spots Dave Almquist wants to check for Colletes ultravalidus. That area has been a productive place for me to find uncommon bees.

I first came in contact with Almquist when I uploaded photos of the globally endangered southern plains bumblebee to iNaturalist in October of 2023. Based on this and other observations I’d made, he invited me to join an iNaturalist project FNAI uses to track species of interest. That same day, I found the bee on the right, an uncommon species John Ascher identified for me. Not a bad day, but neither of those was the bee that brought me to the sandhills.

I found the bee above in October 0f 2021, and Dr. Ascher identified it as Colletes longifacies. He also left a comment on my observation letting me know that it was a rarely observed bee because it flew so late in the year, and that it was endemic to north Florida. He even attached a paper he wrote about the bee. Every once in a while, researchers leave comments to ask questions or share information. It’s a favorite feature of mine.

This is another short-flying cellophane bee, but this time flying in the fall instead of the spring. Like a lot of short-flying bees, it associates with a specific wildflower that blooms either late or early in the year, in this case, the genus Liatris (blazingstars).

Help find potential frosted elfin butterfly sites

The frosted elfin also has a connection to a specific plant, at least in Florida. While the cellophane bees we just talked about have relatively small ranges, the elfin has a range that covers half the U.S.. It had once even extended into Canada. Now, though, it has disappeared from much of its range and is listed as vulnerable in multiple states.

The Munson Sandhills is the frosted elfin stronghold of the American southeast. But that doesn’t mean we can’t try to find it elsewhere. While its caterpillars eat a few different members of the indigo family in other parts of its range, here in Florida, it hosts only on sundial lupine. Find sundial lupine, and maybe you find elfins.

A group of government agencies and conservation organizations has created a citizen science initiative in hopes that you do just that, through the Host Plants of the Frosted Elfin Butterfly iNaturalist project. In our area, sundial lupine blooms from February through late April/ early May. During this time, frosted elfins will emerge from chrysalises in the leaf litter around the plants, mate for a few weeks, and lay eggs on the lupine flowers. By mid-May, elfin caterpillars make chrysalises beneath the leaf litter. There they’ll rest throughout the year.

The project is looking for larval host observations throughout the butterfly’s range. As I learned when I filmed Dean and Sally Jue surveying elfins a few years back, it’s best to walk the area around the lupines with caution. Caterpillars or chrysalises may be on the ground, and you don’t want to crush the animal you’re trying to help.

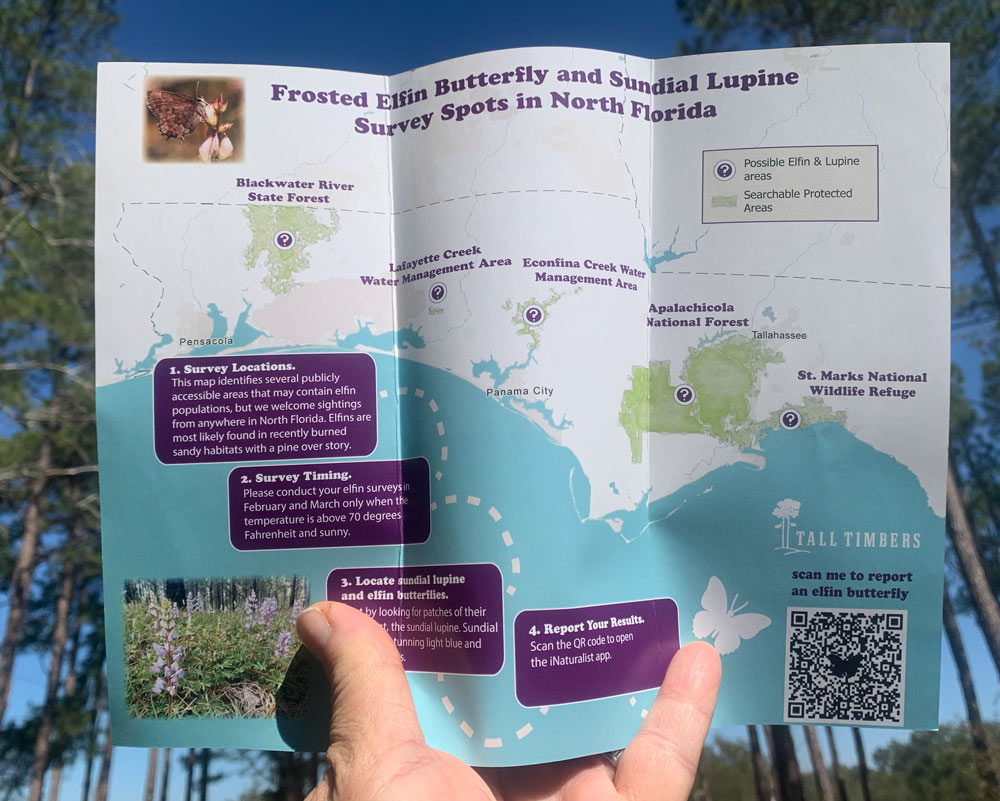

The map above shows where you might find frosted elfin or sundial lupine on public lands in the Florida panhandle.

Lupine species in Florida

While we’re out in sandy areas photographing lupines, here’s a fun fact. A new(ish) fact. The sundial lupines we’re seeking are the only Florida lupines related to those in other parts of North and South America.

“In about 2011 or ’12, we saw that someone some researchers in Switzerland were doing a lot of DNA work on lupines,” says botanist Dr. Edwin Bridges, “And that they were finding that these Florida ones… weren’t related to anything else in North or South America, apparently having come here on some separate radiation from the Mediterranean region.”

That discovery spurred Bridges and Steve Orzell, a biologist at Avon Park Air Force Range, to take a closer look. For decades, they and other botanists had wondered whether Florida had too few recognized species of lupines. Bridges says, “From one region to another, you saw very different forms of what was being called the same species.”

Collaborating with the Swiss researchers who had done the DNA study, they’ve reclassified Florida lupines, adding three new species. They published the research just a couple of months ago, and because it is so new, they’re encouraging iNaturalists to go out and make observations of lupines in Florida.

Unfortunately for north Florida readers, the new species are exclusively in the peninsula. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t make a lupine observation if you see one. Perhaps there may be new discoveries to come, if you’re photos are taken the right way.

Tips for making a good plant observation on iNaturalist

You ride your mountain bike along the trail, find a lupine, and snap a pic. A single pic. Maybe you bothered to walk up close to the plant. Maybe not. What will a biologist learn from your observation?

The best thing you can do to make your observation as useful as possible is to take quality photos and to take photos of the features biologists need to see to make an ID.

“I want at least 3 photos,” says Bridges:

1. The whole plant

“And if there’s something in that indicates the scale of that [plant], that’s even better. Sometimes just having another plant in the photo will show you – is this thing one foot across, or is it three feet across, or is it one foot tall, or three feet tall? Sometimes it’s hard to tell unless you have some reference.”

If it’s a small plant, I sometimes put my hand behind it. This helps a phone camera focus on it if it’s mixed in with other plants, and it gives scale.

2. A closeup of the leaf

“The second is a close-up of the leaf, because many of these are being told apart in our descriptions and keys by leaf characters, not flower characters. So, ideally, what I’d love to see people do is to kind of bend back a leaf from the stem and take a picture of that leaf, showing it from tip to base and showing those two structures that come out off the side of them, which are called the stipules.”

3. A closeup of the flowers

“And then the third, and actually the least important, is the flowers. Some people take a picture of just one inflorescence, and from that, it’s hard to tell which one it is unless you have the geographic context, because flower color is the most variable of the characters in the blue flower lupines. “

He’s talking specifically about lupines, but the same rules apply for all plants. You also, of course, want the bark of any tree you’re trying to identify, as well as acorns, pinecones, fruit, or other reproductive structures. And then any specialized structures a type of plant might have, such as the tendrils some vines use to grab onto a surface.

Any advice for photographing insects?

When it comes to bees especially, get what you can.

You might have luck photographing an insect with a cell phone, especially if it is feeding on a flower. If it is so into its nectar that it doesn’t notice you, you may be able to get close enough for a few good photos.

A lot of the time, however, flying insects are jumpy. If you get too close, you could scare it away, sometimes far away enough that you don’t see it again. I use a DSLR camera to photograph most insects. That way, I can observe it from a respectful distance.

If you can, you’d like to capture as many angles as the insect lets you get. You hope the insect stays in position long enough to get the right angles to photograph it well. It takes some patience. You may have to follow a bee or butterfly as it hops from flower to flower, sometimes taking off right as you set your focus.

If you use a camera other than your phone to make observations, you’ll have to upload it on a computer and place your photos on a map. If your camera has a GPS, that’s one option. Otherwise, how well do you know where you are?

Share your observations!

I hope a few of you head out and see some of these species, and make observations. I’m working on a video segment about this, and when it airs in a couple of months, it would be cool to see that researchers have used data you collected.

As always, observe nature respectfully. It’s better to miss out on a photo than to injure or kill the wildlife we’re there to enjoy. And, if you find anything cool, I’d love it if you came back to this post and left a comment. Or, maybe I’ll see you in person out there as I bushwhack through the sandhills in search of these and other north Florida treasures.