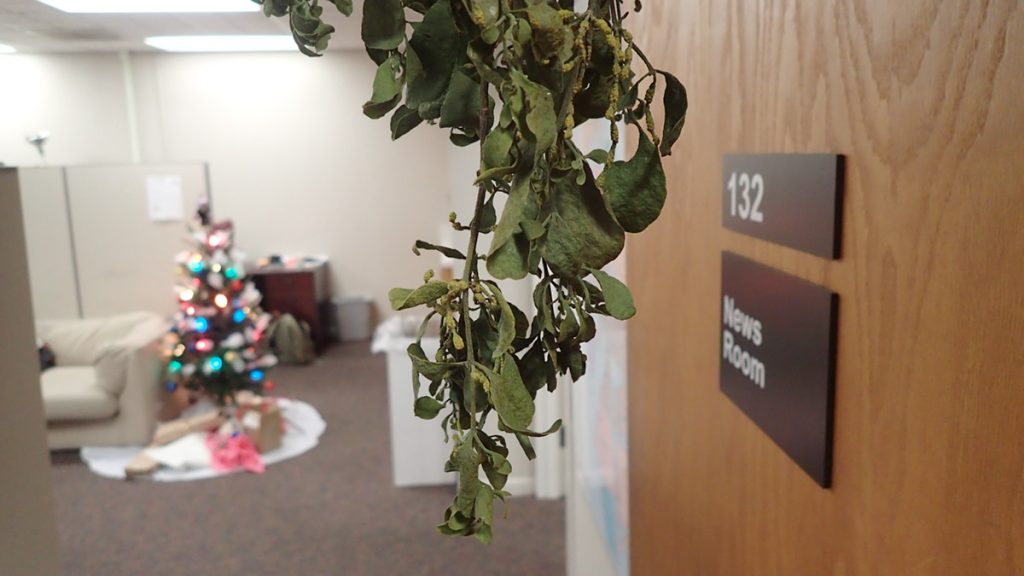

A couple of weeks ago, WFSU-FM News Director Lynn Hatter came into my office. She excitedly told me that there was mistletoe growing in the trees outside. Mistletoe! And here we are in early December, at the right time for a cute holiday plant story. Neither of us knew much about the plant. Was it native? So many Christmas traditions are European, and so wouldn’t the plant be?

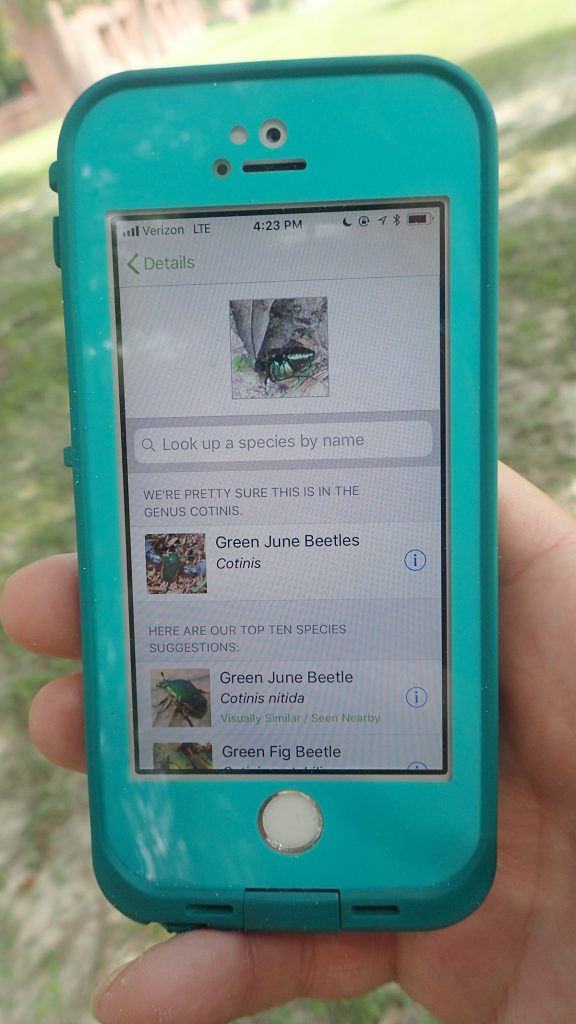

We went outside the building, to three mostly leafless oak trees by the front parking lot. I photographed a few clumps of green growing in these trees, and uploaded the photos to iNaturalist. These were Phoradendron leucarpum, or oak mistletoe (also known as American mistletoe). I looked it up, and this was indeed the species of mistletoe we hang at Christmastime. And yes, it is native, but, oh no- it’s also a parasite.

Bah humbug.

Was this a plant we liked or wanted taken out? I called Leon County-UF/IFAS Extension Agent Mark Tancig for help.

Phoradendron leucarpum | “Tree thief white fruit”

Mark brought a sixteen foot ladder and a pole saw. He cut us down a couple of clumps, and we took a closer look.

“These are the flowers.” Mark said. “So it’s now in bloom. And these will form berries. So this is Phoradendron leucarpum, or American mistletoe. The Phoradendron stands for ‘tree thief.’ The leucarpum stands for white fruit.So it will get these kind of white berry looking things on it.”

Another clump had the beginnings of berries. Within a week, I was able to shoot video of fully ripened berries. The berries and flowers make it a wildlife friendly plant. During our north Florida winters, we do have days that get warm enough for bees and butterflies to fly, and so these winter blooming flowers are a a benefit to them.

And those berries feed squirrels and birds, notably, as Mark tells us, migratory cedar waxwings. Winter berries like those and those of holly trees are an important food source for birds, as insects are less available now. Interesting fact I learned while visiting IFAS on another shoot- even poison ivy berries are a winter food source for our year round resident birds. I can see why. Large flocks of migratory birds like cedar waxwings and robins swarm berry filled trees- it doesn’t seem like an inviting place for a pair of cardinals or chickadees.

So, the leucarpum part of the name refers to a positive for the tree- it feeds our critters. What about the other part of its name, Phoradendron, the tree thief?

Is mistletoe a parasite we can deal with?

“Mistletoe is a hemiparasite.” Mark said. “So, it’s a type of symbiosis where it takes, and doesn’t give anything back. In this case, the mistletoe is stealing water and nutrients from the tree, but can still make its own sugar because it has green color. So, it can still do photosynthesis and make sugars, but it does steal water and nutrients from the tree.”

“Now, will it kill a tree?” Lynn asked.

The short answer is no.

“Because it is a parasite, they typically don’t want to kill their host, right?” Mark answered. “Because if the host dies, they die along with it. It’s a native plant. The trees are native… They’ve had a lot of time to work these relationships out. They are adapted to one another. And as far as the benefits, the benefits really do outweigh the downsides, because it’s beneficial to wildlife.”

So if you see mistletoe in your oaks, it’s probably okay to let them be, or take a little down to hang for the holidays. If you merely cut it as Mark did, it will regrow from the roots, which are inside of the oak tree’s branch. And if you think it, or anything else, is hurting your tree, you can always call the extension office and get some advice.

Mistletoe lore

At the start of the video, Mark makes mention of the legends surrounding the plant. These are of European origin, based on the overseas relatives of Phoradendron leucarpum. As Mark says, the common theme revolves around the fact that mistletoe is green and vibrant when other plants have lost their leaves.

“And, being green and alive during these cold winter periods,” Mark said, people saw it as a sign of strength, fertility.”

“Is that how we got mistletoe and kissing to go together?” Lynn asked.

“I think it has to do with some of the fertility type myths.”

Browsing this page from History.com, we can see that the plant shows up in lore or as a medicine (its vitality as a healing agent) in Greek, Roman, Druid, and Norse mythology. As for the kissing, Avengers fans might be interested to know that Loki, in a Norse myth, seems to be responsible for that.

Mistletoe boys and girls

In the drone shots flying over the oaks, you can see multiple green clumps in the trees. Some are males, and some are females, their mates likely just a branch away. Mark inspected the tiny flowers of the first clump he cut, but could not see the stamens with his unaided eye. So he took it back to the Extension office, and looked under a microscope:

Male mistletoe flower.

Male mistletoe flower.

The male mistletoe flower, stamens highlighted in red circle.

The male produces the pollen to fertilize the female flowers, which produce the fruit.

This species of mistletoe hosts on variety of plants, including, as the name oak mistletoe suggests, on oaks. We recently produced two stories on live oaks, and their place in our urban forest. I also spend a lot of time photographing plants and animals in my own yard. Learning about that flora and fauna, similarly to what we’ve done today, I’ve learned about the benefits or potential problems associated with each species. You’d be surprised at the richness of the backyard ecosystem.

Lastly, a few resources for any backyard research/ citizen science you might want to do:

Apps and Citizen Science mentioned in the Backyard Blog

iNaturalist

Identify plants, animals, lichens, and fungi in your yard. Other users correct your identifications if you’re wrong, and even if they don’t, it can be a good springboard to further research.

Seek by iNaturalist

Instant identification, and it doesn’t record your location. This is a good option for kids with phones.

Monarch Larva Monitoring Project

Enter information about monarch caterpillars in your yard, and help researchers get a sense of the health of the monarch population that year, and how and when they’re migrating.

Great Sunflower Project

Record the number of pollinators visiting your flowers, and help researchers map pollinator activity across the country.

Dig Deeper into Backyard Ecology

What can we do to invite butterflies, birds, and other wildlife into our yards? And what about the flora and fauna that makes its way into our yards; the weeds, insects, and other critters that create the home ecosystem? WFSU Ecology Blog takes a closer look.