Last week, we got a glimpse of the diversity of bird life at Lake Elberta. Now, we look work being done to make this a pollinator hot spot as well. As we see, the work being done here is similar to what we can do to invite wildlife into our own yards. And if you’re interested in Florida Friendly Landscaping, the Leon County IFAS Extension has prepared for us a wealth of information on plant species you can plant in every month of the year.

We’re less than a month away from EcoCitizen Day, where you can observe the birds and pollinators of Lake Elberta. We’re also less than a month away from PBS Nature’s American Spring LIVE (April 29, 30, and May 1 at 8 pm ET on WFSU-TV). EcoCitizen was made possible by a grant from PBS Nature, and is sponsored by the City of Tallahassee. Additional support has been provided by Leon County and Proof Brewing Company. EcoCitizen Day is a part of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s Tallahassee/ Leon County City Nature Challenge.

Subscribe to the WFSU Ecology Blog to receive more videos and articles about our local, natural areas, and subscribe to the WFSU Ecology Youtube Channel.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

Busy hands part the grass to investigate what appear to be weeds. “That’s Rudbeckia hirta,” says Lilly Anderson-Messec, the general manager at Native Nurseries in Tallahassee. “Black-eyed susans.” She points out a small plant with kind of hairy looking leaves. Everyone gets excited. Now Peter Kleinhenz and his Apalachee Audubon interns and volunteers know what to look for.

A few months ago, they planted wildflower seeds here at Lake Elberta. Today, in late February, we’re looking at a flower bed right along the trail that encircles the lake. There’s plenty growing in the grass here. But with each sprout we see, we ask- is this one the wildflowers they hope will enhance the habitat for birds and pollinators here, or a weed? Of course, even the “weeds” might have pollinator value, like the native geraniums popping up here (and in our yards, and pretty much anywhere in Tallahassee).

Lilly is here to help them identify the sprouts, and to offer guidance in how best to weed. Her advice today is to only weed the area right around the wildflower sprouts, because exposing the soil would invite more seeds to land and grow. As a gardener myself, that’s helpful information. In fact, there’s a lot of what Apalachee Audubon is doing here that can apply to what we do at home.

This is the local chapter of the Audubon Society, so they’re focused on birds. Birds need a suitable habitat, and plants are a big part of that. Insects will also benefit; some will feed the birds who call this park home, others are the pollinators we crave in our gardens.

Making Way for Native Plants by Removing Invasives

As Peter says in our previous video, this is a disturbed habitat. It’s a man made lake surrounded by development. As a homeowner, this is what excited me about the habitat building work that Apalachee Audubon is doing here. After all, our homes are disturbed habitat. Much of what works at Lake Elberta can apply to our manmade spaces.

So where do you start?

After Peter applied for and received an Audubon Action grant to fix up this park, one of the first things they did was remove invasive species. “The majority of the invasive species we found out here today were camphor tree, which is a really nasty one,” Peter told us just after their work day last November. “It’s actually the dominant tree in Tallahassee these days. And then we also had a lot of mimosa tree.”

Branches cut from a camphor tree (Cinnamomum camphora) during an invasive species removal at Lake Elberta.

Camphor trees (Cinnamomum camphora) and mimosa trees (Albizia julibrissin) are native to China. Both were brought here to be cultivated, but both species proved a little too effective at reproducing, spreading, and crowding out native species. Removing those trees at Lake Elberta took some hard work. They sawed the plants down to stumps, and then treated the stumps with herbicides to keep them from growing back.

There are hundreds of invasive plants that have become common in Florida. Some are big, obvious trees like those we just mentioned, while others are small, weedy things. And even some Florida natives become invasive in a disturbed environment. Either way, it’s good to know what’s growing in your yard.

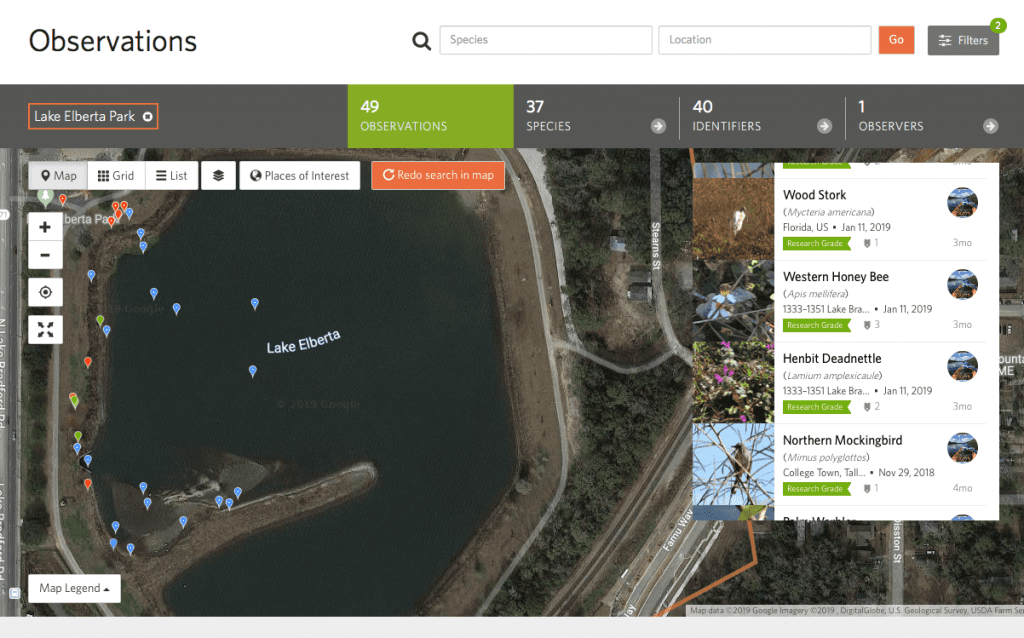

A screen shot of my Lake Elberta observations. Birds are the big attraction at Lake Elberta, but I’m also fascinated by the many flowers and insects there.

Know What’s Growing in Your Yard

There are a few different tools you can use, but my favorite lately is iNaturalist. I know most of you aren’t looking to read up on and learn to identify hundreds of plant species. With iNaturalist, you take a few photos of a plant and upload it. The app makes a few suggestions, and you select one. The iNaturalist community will then weigh in- usually. Even if they don’t, you have a start at identifying this strange plant that’s made a home in your yard.

I usually snap a few photos. One is of the whole plant. I then take a closeup or two of the flowers, and one or two of the leaves. Sometimes I leave my hand in the shot to give it a little scale- it helps you ID a flower if you know whether it’s tiny or huge. I see a lot of folks only take photos of the flowers, but many plants have similar flowers. The leaves and stems can help an experienced botanist or other plant enthusiast see what you have.

Three cell phone photos of clasping venus’s looking glass (Triodanis perfoliata), taken in my yard.

If iNaturalist hasn’t given you a conclusive answer, you can take its suggestions and run it through the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS) plant directory. You can search by common or scientific name, or browse videos and drawings of plants. It can be a daunting database if you don’t know what to call the plant you’re looking at, but those initial iNaturalist suggestions give you a head start.

Once you learn what something is, you can decide what to do with it. As our local IFAS Extension Agent, Mark Tancig, told us “It’s all about, do you like it or not?” He specifically mention venus’ looking glass, a native wildflower that grows in the grass, but that many people pull as a weed. He also pointed out large-flowered pink sorrel, a nonnative with pretty flowers and edible leaves.

Large-flowered pink-sorrel (Oxalis debilis). Non-native, but it has pretty pink flowers and edible leaves.

Learning what you have, and whether it can become invasive, is a good first step in deciding whether you think a plant belongs in your yard.

Several pollinators receive nectar from a goldenrod growing on the shore of Lake Elberta in October 2018. This plant flowers in the late summer and fall, and grows easily in a variety of environments.

Adding Native Plants to the Landscape at Lake Elberta

Of course, if you’re looking to bring pollinators to your yard, you’ll get plenty of flowers by simply not mowing your lawn. We saw that when we first started visiting Lake Elberta in October. Plenty of bees, wasps, and small butterflies had a field day on the flowers growing in the grass.

And that was great between mowings, but the city does regularly mow the park. And some of the most productive pollinator plants don’t necessarily grow in the grass. So, right after they pulled invasives around the lake, Apalachee Audubon planted native plant seeds along a stretch of grass. There were those black-eyed susans, which are a type of Rudbeckia, or coneflower. They also planted native bluestem grasses, which will provide shelter for birds and other critters.

When Peter and Co. went to check out how their seeds had sprouted, they were lucky to have a plant professional like Lilly along. When you plant native seeds, you try to mimic how they would reproduce in nature. A lot of plants drop their seeds as temperatures drop in late fall/ early winter. The seeds have evolved to sit on the ground when its cold, and become active when it gets warmer and they receive rain. Scott Allen-Davis, who oversees the Monarch-Milkweed Initiative at the St. Marks Refuge, told us how we can speed up this process by placing seeds in the refrigerator and then heat shocking them.

But Apalachee Audubon planted in the fall. And in all the time that the seeds sat on the ground waiting to become activated, many other plant seeds made their way into that space as well. Luckily, Lilly was there to tell Peter what was what from all the weedy little leaves popping from the ground. But what about those of us who do this at home? How do we know what’s what?

Mark Tancig passed along an interesting solution. When planting your seeds outside, save a few to plant in a container. Maybe you have a few different species, and you want to label the containers with their names. “And as those are sprouting, you can look closely and get an idea of what you sprouting wildflowers will look like.”

You can also reference this guide to newly sprouted plants.

Bidens alba / Bidens pilosa | A “Weed” that Honeybees Love

After checking the one flower bed, we walk along the lake towards a bed the city planted. Peter, Lilly, and the interns find a common silverbell tree (Halesia carolina) flowering and seeding. Everyone picks the seeds off the tree and continue along the shoreline, where they place the seeds in some mucky opening along the water.

Standing there, Lilly points out the one flower I’ve seen in bloom on every visit to Lake Elberta.

“Bidens alba,” Lilly says. “It’s in the top three of the most important plant for honey bees in Florida. It’s important because one- it’s a composite bloom. So it has plentiful pollen and nectar.” She explained what a composite bloom was the first time I interviewed her, on pollinator gardening. A composite flower will have multiple blooms within it, almost like a bunch of flowers wrapped into one. You can see this in a close up photo:

In the video, we see a honey bee pollinating a Bidens in January. And that highlights another reason this is an important plant. “It blooms practically year round, even if you mow it and mistreat it. And it pops up everywhere. It’s native and it’s a really valuable plant.” A Tallahassee winter can be hot, or cold, or hot then cold over and over again. Most of our flowers disappear at the time of year, and yet it can be warm enough for honeybees and a few other pollinators to come out and seek nectar. When they do, this is one of just a few nectar sources available to them.

And I want to repeat the “even if you mow it and mistreat it” part. Here’s another one that some people see as a weed. If you’ve never specifically paid attention to or noticed this plant before, you’ll now see it everywhere. It’s not picky about where it grows, and it’ll grow big quickly.

Don’t Forget the Larval Food!

They inspect a second flower bed, one planted by the city in the northeast corner of the park. They find a few distinctive looking sprouts, which Lilly identifies as lupines. There are several native lupine species, and in a couple of weeks, we’ll look at a rare butterfly whose caterpillars host on sundial lupine.

Continuing along, we pass some of the trees planted here on arbor day. Many are native species, like longleaf pine, saltbush, and water chestnut. But some were not native.

“What’s interesting is during Arbor day, the City not only planted native trees, but they also wanted to plant fruit and nut trees.” Peter says. “And these are not native to the area. And at first, I thought, ‘Why are we putting exotic trees in?’ But you’re providing things like lemon and nuts and blueberries to the community around you. They can come and basically get a free meal and so can the wildlife.”

Why not plant a little treat for us while planting for the wildlife? And I loved seeing lemon trees, because, much like in my own yard every year, we might see giant swallowtail caterpillars hosting on it.

If you’ve followed the blog for a while, you’ve seen your share of caterpillar related posts and videos. Giant swallowtails are some of my favorites, and in a recent post you can see their life cycle through photographs. Recently, Peter and Lilly have planted food for another favorite caterpillar of mine (and a lot of other folks), the monarch caterpillar. They planted clasping milkweed (Asclepias amplexicaulis), and down by the water, aquatic milkweed (Asclepias perennis).

When thinking about pollinators, it’s easy to think only about flowers, pollen, and nectar. But those are for the adults. It’s equally important to feed caterpillars, to keep producing new generations of butterflies and moths. Larval food plants attract more butterflies to your pollinator garden, which is a plus. And then of course you get to watch their larva transform- first through several instar phases, then into a chrysalis, and finally into a butterfly. That’s something you can watch in your own yard, which is amazing. And, when you visit Lake Elberta to watch wood storks and purple martins, if you take a close look at those lemon trees, maybe you’ll see it here, too.

This monarch was photographed at the tail end of butterfly’s migration south last December. They don’t typically breed during this migration. With new milkweed plants at Lake Elberta, perhaps more monarchs will visit during the northern migration over spring and summer, and leave caterpillars to host on the plants.

Pale-edged Selenisa (Selenisa sueroides), a moth caterpillar having a meal on a pea plant in the vegetation at the lake’s edge.

WFSU EcoCitizen is funded by Nature, a production of THIRTEEN PRODUCTIONS LLC for WNET and PBS. American Spring LIVE is a production of Berman Productions, Inc. and THIRTEEN PRODUCTIONS LLC for WNET.

Major support for Nature: American Spring LIVE was provided by the National Science Foundation and Anne Ray Foundation.

Additional financial support was provided by the Arnhold Family in memory of Henry and Clarisse Arnhold, Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III, the Kate W. Cassidy Foundation, the Lillian Goldman Charitable Trust, Kathy Chiao and Ken Hao, the Anderson Family Fund, the Filomen M. D’Agostino Foundation, Rosalind P. Walter, the Halmi Family in memory of Robert Halmi, Sr., Sandra Atlas Bass, Doris R. and Robert J. Thomas, Charles Rosenblum, by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by the nation’s public television stations.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1811511. Any

opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and

do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.