One night in August, as he was getting ready to go bed, Dr. Lee Bushong received a phone call. On the line was Worrel Diedrick, an entomology Ph.D student at Florida A&M University, and Lee’s beekeeping partner. A woman had called the extension office with a bee issue. It seemed that bumblebees had formed a colony in one of her bird gourds. While she didn’t want them on her property, she did want these useful pollinators to find a good home. Lee was intrigued.

They placed the gourd in a butterfly tent and moved it to Lee’s house, where I met with them a week later. Lee, a professor of forensics at FAMU, has taken three quarters of an acre in his yard and planted native pollinator plants. He also raises honeybees, which we visited with as well. This would make a good home for what turned out to be an increasingly rare species of bee.

“Bombus pensylvanicus,” Worrel said, “They are endangered, and their habitats are being destroyed, based upon agriculture, extensive agriculture production.” Technically, this bee is listed as Vulnerable (G3), the conservation status just below Endangered. But it had once been the most common bumblebee species in the United States.

“I’m somewhat pleased, having learned, you know, exactly what they are that this is a bee that’s at risk.” Lee said. “To be able to provide a sanctuary where they can, not just live, but thrive.”

The common name for Bombus pensylvanicus is the American bumblebee. Looking at iNaturalist observations for bumblebees in the state of Florida, we’re more likely to see the common eastern bumblebee (Bombus impatiens) in our yards. Getting to know this larger, rarer bumblebee can teach us a lot about all of the bees that pollinate our favorite flowers.

Solitary vs. Social | Not Just Honeybees Make Hives

When talking about our local bee population, it’s helpful to differentiate between honeybees and all the rest. Honeybees are of course important. No, they’re not native; they’re instead an agricultural animal with a job to do. And we’ll talk about them in a little bit. Lee and Worrel showed us their hives, and shared some insights into their social structure and the pests that threaten them.

Our non-honeybees are a diverse lot. There are over 300 species of native bees found in Florida. They come in all shades of blue, green, and yellow, sometimes clad in all black save for golden pollen sacs on their legs. They range in size from the conspicuous carpenter bee to sweat bees that, unless you zoomed in with a good camera or binoculars, you might mistake for small flies.

Most of these native species are solitary, and most nest in the ground. So I was surprised to learn that bumblebees are, in fact, social bees. As Worrel describes, bumblebees have “somewhat of a plastic relationship, where they’ll start out solitary and where you’ll find one queen go and establish their nest.”

The life cycle of the American Bumblebee

In the late summer, queen bees hatch and mate. They then enter a state known as diapause, where they suspend their development, until the following spring. Around February/ March, they’ll come out of diapause and look for a place to start their nest.

They’ll produce two batches of workers. The first is smaller. That generation raises a second, larger brood which hatches in the middle of the summer. “So they have cooperative brood care and overlapping generations,” Worrel said.

Reading up on Bombus pensylvanicus, I see that the queen meets a brutal end. This happens after she lays her final eggs, which are not workers but queens and males. After she lays these eggs, the female workers also start laying eggs, but the queen tries to destroy them. The other females understandably do not like this. By the time summer ends, the workers finally sting the queen to death.

The workers themselves won’t make it through the winter. All that’s left of this species in the colder months is that last batch of queens, resting in the ground, the beginnings of next year’s nest within them.

This species of bumblebee nests above ground, which may make their nests more vulnerable to destruction than other, ground nesting bumblebees. In this case, they nested inside of a human made structure. The gourd’s small openings made it challenging to get shots inside without disturbing them, but we can still see the rough structures they constructed inside of it. These are like the much tidier hexagons in a honeybee hive- these house the larvae (the hexagons also store honey, which bumblebees don’t make).

Inside a Honeybee Hive

Now, for comparison, let’s take a look inside Lee and Worrel’s honeybee hives. Unlike honeybees, American bumblebee queens and workers look about the same; the main difference is the larger size of the queen. The male is the smallest of the lot, and slightly more covered in yellow fuzz. At a glance, they’re all fairly similar in appearance.

A queen honeybee is easier to distinguish from the workers. Not only is she bigger, but she has an elongated abdomen:

The male, or drone, is most easily distinguished by his eyes. They’re much larger than females’ eyes, and almost touch each other. This gives them better vision for their one job, to find a queen while in flight, and mate with her.

All those other bees, they’re the workers. The younger workers take care of the brood, and when they’re older, they forage for nectar. They’ll die after flying about 500 miles, typically after 5-6 weeks.

Lastly, here are their larvae. They live in the hexagons at the center of the frame. The honey is in the hexagons at the top of the frame.

Colony Collapse and Hive Pests

Lee and Worrel are on a mission to breed a better bee.

“Breeding a bee is simple in my opinion, right?” Lee said. “Once you’ve mastered the art of it, it’s not really difficult. But breeding a bee that is viable is something that’s totally different. So we’re looking for a bee that’s resilient.”

Like beekeepers across the world, Lee and Worrel have colony collapse on their mind. This is, in fact, the primary focus of Worrel’s Ph.D work- improving the health of honeybees.

“It’s a combination of management,” Said Worrel about colony collapse, “It’s a combination of pests, it’s a combination of improper pesticide use, monocropping, you know, agricultural practice, and, as I said, urbanization, where habitats are being destroyed.”

Habitat loss is a likely cause of the decline of Bombus pensylvanicus as well, and of pollinators in general. We talked about that earlier this year in a segment on milkweed, where we learned that even in existing longleaf pine forests, a lack of prescribed fire often allows woody plants to crowd out flowers in the understory. So how habitats are managed is a factor as well. And, just as we can offset the loss of wild milkweed by planting in it our yards, we can help all pollinators- and not just those monarchs we love– by planting a variety of native pollinator plants.

At Lee’s house, habitat is not a factor. Nor is pesticide use. Lee and Worrel are, however, concerned about pests.

Varroa Mites and Small Hive Beetles | Bee Hive Pests

The two main pests are Varroa mites and small hive beetles. We didn’t see any Varroa mites (Varroa destructor), and in general, they are small and not so easy to detect, at least not before their infestation has become well established. The trick is to not let them become established.

“Early detection of low levels of mite infestation is key to successful management.” Writes Ric Bessin, Extension Entomologist for the University of Kentucky. These minuscule pests attack both adults and larvae, sucking their blood and weakening adults, and causing deformities in the brood.

While we didn’t see Varroa mites, we did get to watch Lee hunt down and trap small hive beetles (Aethina tumida) in one of their frames.

As Worrel explained, these beetles don’t attack honeybees directly. After pupating in the soil, “those small hive beetles lay their eggs inside the stored honey. When those eggs emerge into larvae, those larvae will burrow through the honey. And they would, you know, pass their waste and they would cause their stored honey to become acidic. And moisture levels increase, and it would cause bees to just abscond and leave the hive.”

Lee and Worrel’s goal is to breed bees that can deal with pests like these. This means attacking pests and removing dead bees to prevent the spread of disease.

The Pollinator Habitat | Animals We Saw in the Video

Now let’s circle back to habitat loss. In my reading on the decline of Bombus pensylvanicus, researchers have a hard time pinpointing a specific cause. But they do note a correlation between loss of habitat, especially to large farm operations, and agriculture practices that reduce plant diversity.

I’ve already mentioned Lee’s three quarters of an acre pollinator space. Not all of us have this much land to work with, but we can choose to plant native wildflowers and larval food for butterflies in the space we have. The more people who do this, on a large or a small scale, the less isolated these patches of habitat become.

In the next section we’ll look at Lee’s home habitat, and list the species we saw there. In the following section, we’ll share images and some information about some of the other native bee species in our area.

As always when we list species in the video, we won’t list every shot, as we see the same animals in many shots. But I try to identify every plant and animal we saw.

What We Saw:

0:02 An American bumblebee on what might be a type of sage. That’s iNaturalist’s first guess, but I’m not sure. Either way, you can see that most of the flowers are spent.

0:53 Gulf fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) on orange cosmos (Cosmos sulphureus) flower.

1:41 Several dotted horsemint, or spotted beebalm, (Monarda punctata) flowers. You see the plant a lot in this segment, and you’ll see it a lot in the next, when we visit the Cherokee Lake Pollinator Garden in Thomasville, Georgia. I shot both segments in August, when the plant was also attracting a lot of pollinator attention in my yard.

1:44 A little collage of native bee species, which we’ll explore in the next section.

2:17 American bumblebee on basil flowers (the banner image above). People will cut off basil flowers to keep the plant’s energy in leaf production. But bees love basil flowers.

4:22 A couple of shots of American bumblebees on beebalm.

4:31 Here we see two solitary wasps on beebalm. On a visit to Native Nurseries, I was told that this plant would attract solitary wasps, and it was true in my yard as well as here. iNaturalist didn’t have a specific ID suggestion for the first wasp, but two users have suggested the genus Tachytes, sand loving wasps. The second wasp in the shot (pictured above), which we see after the rack focus, is a feather-legged Scoliid wasp (Dielis plumipes).

4:45 Clouded skipper (Lerema Accius) butterfly on a blue lobelia flower.

5:06 Zebra longwing, or zebra heliconian (Heliconius charithonia) on orange cosmos flower.

5:30 Green lynx spider (Peucetia viridans) on basil leaves. I know Worrel was talking about predatory insects at this point, but spiders are important predators as well, right?

5:33 This is an obscure bird grasshopper (Schistocerca obscura). We talk a lot about pollinator gardening, but really, there are a suite of animals that we’re inviting into our yards. We want to create, as Worrel says, “a complete ecosystem.”

Native Bees of North Florida

I edited the following section in June of 2020 to add a bee species. In researching the sweat bees I saw in our yard in May 2020, I’ve learned information which I’ve also added.

I talked about the diversity of native bees above, and it so happens I have a few photos to share. These were, for the most part, taken for the Backyard Blog, a section of this blog where I photograph plants and animals in my yard, and try to learn as much as I can about the ecology of my home space. There are many stories to tell in the home ecosystem.

This is not a comprehensive list, but a sampling of common species you might find in your own yard. And I will say that until I started stalking my flowers with a camera, I hadn’t noticed just how many cool looking bees I had in the yard.

The Big Bees (the ones that look like bees)

Yes, the ones that look like bees. By which I mean, the ones most people would have no trouble identifying as bees, at a glance.

Eastern Carpenter Bee (Xylocopa virginica)

The largest bee you’ll see in our area is the eastern carpenter bee, which is just slightly larger than a bumblebee. Females cut perfect circles into wood so that they might build a nest. One such abandoned nest in the railing by our back door, has more recently become home to a four-toothed mason wasp, and a cuckoo wasp which has likely been laying its eggs in with the mason wasp’s (these are the kinds of things I learn about in the Backyard Blog).

Common Eastern Bumblebee (Bombus impatiens)

The more common bumblebee in our area, here on a pentas flower, like the carpenter bee. It helps provide scale when multiple pollinators use the same flowers.

Sweat Bees (the small, shiny, and sometimes colorful guys)

This is a diverse lot. Some sweat bees are brightly colored, and draw the eye. Others are small and black, and would appear as flies to the naked eye. Take a closer look at those small insects pollinating your flowers, and you might find thee fascinating little bees.

Augochlorine sweat bees

Augochlorine might be my favorite bees. This year, they loved our winged loosestryfe, which made them difficult to photograph. The plant sports a multitude of small flowers, and so bees typically don’t take long to take pollen from each. Not helpful when I’m trying to frame and focus.

Using iNaturalist, I see two almost identical bees in this tribe, so I’m not 100% on whether this is a pure green sweat bee or a metallic epauletted sweat bee. I made this specific ID based on its behavior, specifically, that pure green sweat bees nest in rotting wood.

In 2019, I first saw these bees while removing an old wooden bench from the yard. I must have disturbed a nest? I waited to throw the wood out, and left it in a pile off to the side. I then saw the bees check out several bare patches of earth, another place they nest.

Brown-winged Striped Sweat Bee (Agapostemon splendens)

Here’s a sweat bee I had seen once or twice in recent years. In late summer 2019, though, we must have had a dozen at any given time. I’m in the process of rehabilitating part of my yard, removing pavers (creating space for ground nesting bees), and planting patches of wildflowers (feeding those bees). These are small, fast, and difficult to photo; I was happy to have this one check out a larger flower, a purple coneflower, on which it lingered longer than on loosestryfe or sage.

Poey’s furrow bee (Halictus poeyi)

When fanpetal flowers open, they’re about a centimeter and a half in diameter, maybe less. This pollen covered Poey’s furrow bee fit snuggly within one.

Lasioglossum, subgenus Dialictus

Two small bees on pentas flowers.

Eastern Carpenter Bee (Xylocopa virginica) on pentas.

Again, pentas serve as a basis for comparison in bee sizes. The bees on the left were too small to get a clear photo of them, at least one where iNaturalist users could tell me more than these were metallic sweat bees of some of the subgenus Dialictus. The image on the right is that carpenter bee again, and it is actually zoomed out further than the image in the left.

Dialictus is a subgenus of the Lasioglossum genus, and it has hundreds of very similar looking bees. They are difficult to differentiate, even with a microscope. I see quite a few in my yard, and some are slightly larger than others. I figure, based on size, that I have at least two species.

On fanpetal flower

Red salvia

Goldenrod

Other Native Bees

Two-spotted Long-horned Bee (Melissodes bimaculatus)

I repeatedly saw one or two of these bees in my yard in July. In August we had an explosion of sweat bees on these same plants, and I didn’t see the two-spotted long-horned bee again.

Leafcutter bees (genus Megachile)

I’ve seen a couple of these in the yard. I only got one photo of the one below, and didn’t see enough of the bee before it flew off to get a more specific ID than its genus.

In May of 2020, we had a leafcutter that became a regular visitor in the yard, and I’ve been able to take several photographs of it:

It’s an aggressive bee, chasing off wasps and other bees of similar size (in particular the two-spotted longhorn).

Dig Deeper into Pollinators on the WFSU Ecology Blog

Pollinator gardening has been a frequent topic on the WFSU Ecology Blog, and we’re in the process of partnering with some of our local experts to bring you more stories and helpful tips.

You can start by browsing our stories on pollinators, from rare butterflies to those you raise at home.

And, again, I’ll mention the Backyard Blog. I’ve tried to find out everything I could about the many insects in my yard, beneficial or not. And of course, knowing what you have is the first step to knowing whether an insect is beneficial or not, and even some of the “pest” species, in small numbers, are part of my yard’s biodiversity and food web. Birds have to eat something, after all.

I’ve also been looking into all of the weeds in my yard, discovering which are invasive, and which are natives with surprising ecological value.

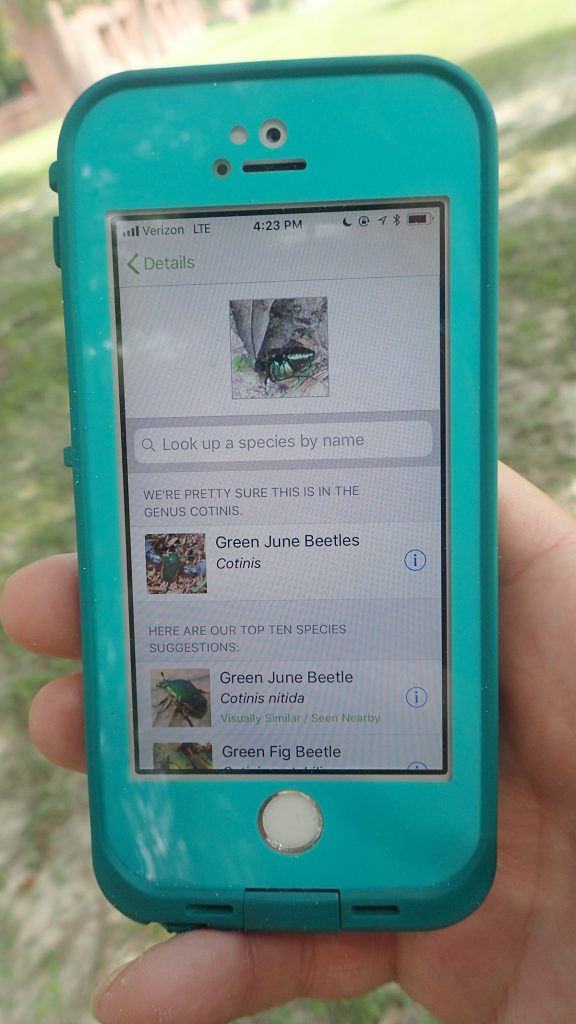

Lastly, I’ll include this module that’s on every Backyard Blog page. I mentioned iNaturalist a bit in this post, and it has become one of my primary tools for identifying plants and animals. Your yard can also be a citizen science lab, helping researchers collect data on pollinators across the country, yard by yard.

Apps and Citizen Science mentioned in the Backyard Blog

iNaturalist

Identify plants, animals, lichens, and fungi in your yard. Other users correct your identifications if you’re wrong, and even if they don’t, it can be a good springboard to further research.

Seek by iNaturalist

Instant identification, and it doesn’t record your location. This is a good option for kids with phones.

Monarch Larva Monitoring Project

Enter information about monarch caterpillars in your yard, and help researchers get a sense of the health of the monarch population that year, and how and when they’re migrating.

Great Sunflower Project

Record the number of pollinators visiting your flowers, and help researchers map pollinator activity across the country.