How healthy is the pollinator population in Georgia?

“You never would have thought nature was so intriguing.” There’s a small crowd around an overturned leaf, looking at what appears to be a shiny bird poop. Two Thomas University students make note of it on their clipboards. The poop they’re looking at is, in actuality, the caterpillar of the giant swallowtail butterfly. It’s on its host plant, the common hop tree (Ptelea trifoliata), a member of the citrus family native to north America.

We’re at the Cherokee Lake Pollinator Garden, a stone’s throw from one of Thomasville’s better known attractions, its Rose Garden. It’s late August, and the place is swarming with insects of all sizes, colors, and shapes. The students, along with volunteers of all ages, are here to take part in the first ever Great Georgia Pollinator Census.

All across the state, people are picking a single plant, and watching it for fifteen minutes. Then it’s on to another plant, and another. Alisha Clayton, one of the students, explains. “Whatever sort of insects or animals that we see, crawling around the tree, or making a habitat of the plant, then that’s usually what we record.”

I take my camera over to a beebalm patch, which, at this time of year, is in full bloom. We do, of course, see bees pollinating it, mostly carpenter bees today. Despite its name, though, it might actually be more popular with wasps. I also record a housefly in one of its flowers.

Over a couple of hours, we see multiple species of caterpillar on their host plants, praying mantises, leaf footed bugs, and many other entomological odds and ends. Along with compiling pollinator data, our noticing these insects is the point of this event.

This is Cherokee Lake. If you zoom into the area north of the Rose Garden, you’ll see a butterfly shaped patch of darker green. This is the Cherokee Lake Pollinator Garden. The garden is maintained by the Friends of the Lost Creek Forest (we’ve done stories on the Lost Creek Forest, and the Wolf Creek Trout Lilly Preserve, which the friends also help maintain). You can keep up with the Cherokee Lake Pollinator Garden on Facebook.

Citizen Science | More than merely research goals

The University of Georgia Cooperative Extension had three goals for the census. Like many citizen science initiatives, only one of the goals is directly related to the data collected. In fact, when I talked to census coordinator Becky Griffin, that was the last goal she listed.

We’ll talk about those goals in a second. First, let’s take a look at participation. After all, this kind of citizen science project doesn’t work if there’s only patchy participation from only certain parts of the state.

“I truly was just hopeful for a thousand counters,” Becky told me, “And we had almost 5,000. We had 4,698 counts submitted.” This was across 134 of 159 Georgia counties, roughly 84%. So they had what they considered to be a good quantity of counters, covering a good amount of the state. But what of the quality of the counts?

This is where people are sometimes skeptical of citizen science. It’s all well and good to engage a lot of “regular folks” to help out researchers. But those researchers often have Ph.D’s in their field of study. How can we trust the public to identify any of thousands of insects they might encounter in their garden?

Becky worked for two years tinkering with the way in which citizen scientists would be trained to ID insects. “I had two pilot projects in 2017 and 2018. And during that time, we recruited gardeners of all ages, including school groups, and trained the teachers. And [we] worked on refining what we were asking them to identify at that level.”

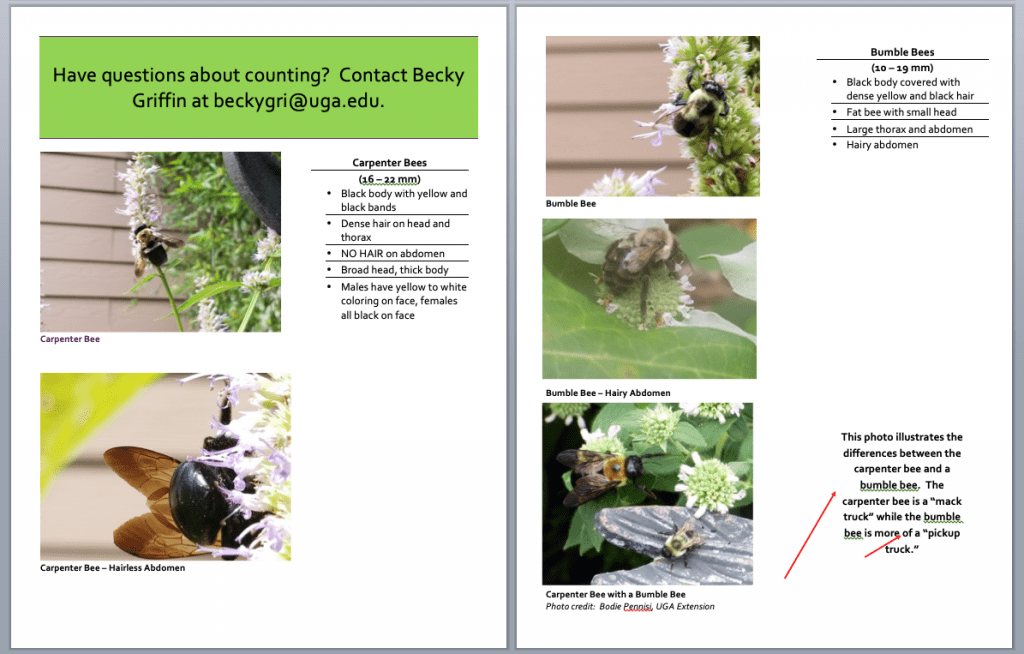

The resulting ID guide doesn’t list every possible insect they would see. Rather, we see the more common butterflies, and tips for differentiating groups of bees, wasps, and flies. For instance, there are 400 species of native bees in Georgia (in addition to the nonnative honeybee); those were organized into six categories.

Goal 3: Generate a Snapshot of Georgia’s Pollinator Population

Becky listed this last, but we’ll talk about it first. I’m doing that because, in talking about this goal, we get a sense of a problem. Talking about the next two goals, we start working towards a solution.

This last goal is to get an overall sense of how many pollinators there are in the state of Georgia, and to see, generally, how many of each type of pollinator. The UGA Extension cares about this because pollinators are on the decline. This is a thing we hear a lot, but much of the research to support this has focused on specific species, notably honeybees (which are not native) and monarch butterflies. And there are studies on pollinator decline in relation to agricultural practices and habitat loss.

We know that pollinator habitat is on the decline (as we discussed in our segment on milkweed earlier this year), and that specific species are imperiled. What the University of Georgia wanted to know was, how are pollinators doing overall in this state?

Following August’s census, they have the numbers. They received over 130,000 observations. As Becky tells me, Georgians counted around 20,000 small bee species. This includes anything smaller than honeybees and native carpenter and bumblebees; many of them, without closer inspection, look like flies. She considered it good news. “Not only that those bees were there, but that people learned enough entomology through the program to actually put them in that category.”

They also counted over 30,000 butterflies, and what Becky says were a good number of bumblebees and flies, noting that citizen scientists were distinguishing bees from bee mimics such as syrphid flies (a favorite of mine, as you can see from the number of times they’ve appeared on this blog).

But what do those numbers mean?

Without any numbers from prior years, this is an interesting snapshot, but we don’t get a sense for whether or not pollinators are declining or rebounding, or even holding steady. There’s no baseline, no numbers to compare with this year’s results.

However, there is already a 2020 census scheduled for August 21 and 22 of next year. “The 2019 census will serve as baseline for future censuses.”

Goal 2: Increase the Entomological Literacy of Georgia Citizens

Ideally, citizen science is a win/ win for researchers and participants. Researchers get valuable data collection that might be otherwise financially prohibitive. There aren’t many labs, after all, that could afford to pay 4,500 lab technicians for a massive sampling effort.

The citizen scientists themselves, at the very least, learn something new. But UGA is hoping for something bigger. With that education, and in taking the time to do nothing but look at insects and plants for a bit of time, they’re hoping citizen scientists change their perceptions of insects as a whole.

“We found that, a lot of times, people don’t really understand insects,” Becky said. “People think they’re pests, as opposed to helpers, like pollinators. So we just wanted to teach people how to do some basic identification… so that they could really appreciate these insects.”

Learning to identify insects is key. Once you know what you have, you get closer to learning its role in your garden. And observing helps as well. Paying attention while doing your yard work, or taking time to specifically watch the goings on of your garden residents, you see the insects in action. What you start to see, as we saw at the Cherokee Lake Pollinator Garden, is a complete ecosystem in which plants, insects, and other animals are interdependent.

Predators

I’ve seen memes on Facebook depicting bees as noble pollinators and wasps as biting… well, I’ll not use that word on the blog. As we see in the video, though, wasps are a diverse group of pollinators. And, they’re predators. We see one tackling a butterfly caterpillar, which I don’t love (and they go after first instar monarch caterpillars in my yard). But they also hunt what we consider garden pests in the yard, those moth caterpillars that eat our food plants. They don’t eat the caterpillars themselves; rather, they bring them back to their nests to feed their larvae.

We also saw two praying mantises, which are just fun to watch.

Learning about predator insects has changed what I think about insects in my yard as a whole. I see “pest” caterpillars in my yard from time to time, but rarely do they do a lot of damage to my food plants. I also see predators like assassin bugs and hanging thieves, and I see birds pecking at my plants. Knowing I have predators to keep the balance, I don’t let myself become bothered by one stinkbug here or a cutworm there.

Relationships Between Insects and Plants

This leads into Goal #1. In the video above, we see three different butterfly caterpillars on their host plants. That’s four if you count the caterpillar we see the wasp attacking on the fanpetal (checkered-skippers do host on fanpetals, but that insect getting tackled by the wasp is in an un-identifiable state).

“Each butterfly can only lay its eggs on specific plants.” says Beth Grant, who organized the Cherokee Lake count in Thomasville. “Probably the one that people know the most is monarchs. Monarchs will not lay their eggs on any plants except milkweeds.”

Earlier this year, I put together a short guide to raising four butterfly species. Each has their own host plants, and usually with native and nonnative species. The example Beth gives is the giant swallowtail, which hosts on members of the citrus family. At Cherokee Lake, they plant native hop trees for this purpose. In my yard, they host on a nonnative Meyer lemon tree.

We can see that planting a pollinator garden is more than just pretty flowers and butterflies. It’s an ecosystem that starts with the right plants, which attract insects of all sorts for shelter and food. They in turn attract predator insects, spiders, birds, lizards, frogs, and so on. If we build the stage properly, we’ll never stop seeing the myriad dramas that play out between all of the players we’ve invited.

Goal 1: Create Sustainable Pollinator Habitat Across the State

This is the goal Becky stated first, and for good reason. The University of Georgia Cooperative Extension isn’t merely interested in measuring decline or growth of pollinators, they’re looking to encourage action towards building a healthy environment for insects. Insects are at the bottom of the food web; maintaining a healthy insect population ensures that a larger segment of our wildlife gets fed.

A study released last year found that yards with less than 70% native plant biomass were less likely to sustain songbird populations. Our native insects have longstanding relationships with native plants. If you have less of the plants that bugs like to eat in your yard, the insect populations will adjust to the amount of available food. Those shrinking numbers will then ripple upwards through the food web. Songbirds eat a lot of insects, and nesting birds need caterpillars in particular.

We’re not just talking about flowers.

We might not always see it because much of the action happens high up where we can’t see it, but native trees host a wealth of insects. We recently looked at the ecology of live oak trees, and oaks of all species support hundreds of insect species. Their acorns feed squirrels. Birds nest in them. Even other plants grow on them.

Now look down. What covers the ground in your yard? At the Cherokee lake Pollinator Garden, we see some alternatives to turf grass, plants that I’ve been experimenting with in my own yard. Sensitive plants (Mimosa pudica) are native, and offer pollinators fuzzy pink flowers. Turkey tangle fog fruit (Phyla nodiflora) has flowers, and is a larval food for three butterfly species: common buckeyes, phaon crescents, and white peacocks.

These are just a couple of examples of trees and groundcover plants. It’s also important to have a diversity of plants, and types of plants. There are also a variety of native shrubs, so you can put in plants at multiple heights. And if you’re planting larval food plants, group them in threes- butterflies are more likely to smell them.

If habitat loss is to blame for a certain amount of pollinator decline, then we can all help by creating habitat in our own spaces. It’s no replacement for large swaths of intact forests and prairies, which we are lucky to have in our area. But in a time where we are inundated with negative environmental news, here’s a little thing we can do to improve the story.

“[People] hear so much negativity that they just can’t handle anymore,” Becky said. “So let’s be positive. All right? What can we do to help insects? Can we learn more about them? And can we create habitat, can we help document them? And therefore we have more control over this big problem.”

Don’t when to plant trees, shrubs, and flowers? Consult this handy seasonal planting guide, created with the Leon County- UF/ IFAS Extension.

What did we see in the video?

So let’s ID some insects! What I did for this video mis similar to what I do when I look at the insects in my own yard, a process I document on the Backyard Ecology Blog. As I do there, I’ll talk a little about how I go about finding out what’s what.

My primary identification tool is iNaturalist, an app you can use on your phone, or upload photos onto later. It scans the photo and lists suggestions based on what it sees. Then a community of users verifies or suggests a different species. I started using this for the WFSU EcoCitizen Project, which also encouraged citizen science and building pollinator habitat. Using the app, you can both catalogue the flora and fauna of your yard (well, anywhere you go), but you also learn what every plant and animal is, and start to understand its role in the home ecosystem.

00:02 Giant swallowtail butterfly nectaring on pink swamp milkweed. Milkweed is the larval food of the monarch butterfly. But its flowers are popular with many other butterflies, as we’ll see.

Some species on beebalm

00:06 Eastern carpenter bee (Xylocopa virginica) nectaring on dotted horsemint (Monarda punctata), aka spotted beebalm.

00:09 Great Black Digger Wasp (Sphex pensylvanicus) on beebalm. Beebalm is popular with solitary wasps, many of which are similar looking. Another iNaturalist user disagreed with my initial guess, and so I clicked the compare button on their recommendation. This put my photo side by side with other user photos of the species, and this window also has a map of where the species has been spotted. Just because it hasn’t been spotted in our area by other iNaturalist users, that doesn’t mean it automatically disqualifies this identification. But the recommendation might be for a west coast relative of an east coast species, or something from quite far away. It’s helpful information.

00:13 Oriental latrine fly (Chrysomya megacephala) on beebalm. So far we’ve seen a bee, a wasp, and a fly pollinating this plant. Also, iNaturalist tells me this is a nonnative species (these are marked with a pink exclamation point).

A diversity of garden insects, in various forms

00:16 Poey’s furrow bee (Halictus poeyi). This is a small bee species I often see in my own yard. Without getting up close you wouldn’t know this was a bee. This is one species that has allowed me to get up close to it while nectaring.

00:26 Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) nectaring on pink swamp milkweed.

01:07 Gulf fritillary butterfly (Agraulis vanillae) chrysalis.

01:10 Gulf fritillary caterpillar grazing on passionvine, its larval food plant.

01:13 Likely a Carolina mantis (Stagmomantis carolina).

01:35 Eastern carpenter bee (Xylocopa virginica) on false dragonshead. This species looks a little bit like a bumblebee. The easiest way to tell the difference, using the ID guide created by the UGA Extension, is the abdomen (its backside). The carpenter bee has a hairless abdomen, while bumblebees’ are fuzzy.

01:39 Honeybees in their hive (from our last segment on American bumblebees).

01:40 A small bee on beebalm, possibly a sweat bee. I’d need a longer lens to get a close enough shot to properly identify it.

01:41 Noble scoliid wasp (Scolia nobilitata) on turkey tangle fog fruit. This wasp was small in the photos, so I cropped it to upload to iNaturalist (the reason this image is smaller than the rest). The app presents suggestions based on what it sees in the photo. Before cropping, it would likely have ID’d the many flowers in the frame; by removing most of them, I put an emphasis on the wasp. In this instance, the wasp had not been previously observed in Thomas County. It had, however, been observed in surrounding counties in south Georgia and north Florida.

01:43 Mottled tortoise beetle (Deloyala guttata) on sensitive plant (Mimosa pudica).

01:48 A couple of shots of gulf fritillary caterpillars on passionvine (Passiflora genus).

Monarchs and milkweed

01:58 Monarch caterpillar grazing on swamp milkweed flowers; the camera then racks to an adult butterfly nectaring on other flowers on the plant. I’ve often noticed that smaller monarch caterpillars hide in the flowers of the plant, where they’re less exposed than on a leaf. This is a fourth or fifth instar caterpillar, soon to make a chrysalis.

02:13 Monarch chrysalis, a photo taken in my yard.

Giant swallowtail butterflies on plants of the citrus family

02:23 Here, the monarch caterpillar is joined on the milkweed’s flower by a giant swallowtail butterfly. The largest butterfly in our area, this is Georgia’s official state butterfly.

02:32 The scene I describe at the start of this post; volunteers finding a caterpillar. We see the distinctive pink swamp milkweed flowers, but here they’re intertwined with the hop tree to their right.

02:37 A middle-instar giant swallowtail caterpillar. You can see all of the instars of this caterpillar in our earlier post on raising different butterfly species.

02:39 A young Meyer lemon, in my yard.

02:43 A later instar giant swallowtail grazing on a Meyer lemon leaf.

Gulf fritillary butterfly and passionvine

02:52 Gulf fritillary butterfly sunning on passionvine leaf.

02:56 Gulf fritillary caterpillar on vine, among several buds, some of which are starting to blossom.

02:59 Passionvine fruit, or as Beth calls, them, maypops.

03:11 Gulf fritillaries nectaring on passionflower and on passionvine leaves.

03:15 A couple of shots of fritillaries ovipositing, or laying eggs, on passionvine leaves. I’m not entirely happy about how quickly I framed and focused after spotting them, but still thought it was worth showing this activity.

03:22 Fritillary caterpillar on passionvine, with a chrysalis on an adjacent plant. The vine has grown over two different flowering plants, including a fanpetal (the plant in the foreground).

Checkered-skippers and fanpetals

03:25 Beebalm on the left, a passionvine bud on the right. The flower between them that racks into focus is a fanpetal.

03:27 Female tropical checkered-skipper (Pyrgus oileus) nectaring on a fanpetal flower. This is a photo from my backyard; I did not see checkeed-skippers on fanpetals at Cherokee Lake. The female tropical checkered-skipper looks much like a male white checkered skipper (Pyrgus albescens), the difference in their marking is in the upper tips of their wings. The patten on the edge of the wings becomes smudged on a tropical checkered-skipper.

3:30 Tropical checkered-skipper curling its abdomen onto a fanpetal bud. This is typical of a butterfly laying its egg. I could not, however, find an egg. It may be that, like the frosted elfin (which we observed ovipositing earlier this year), they may try to hide their eggs in this part of the plant.

3:36 Guinea paper wasp (Polistes exclamans), wrestles with something in a cluster of fanpetal flowers. It turns out to be some sort of insect larva. I can’t say for sure that it’s a checkered-skipper caterpillar, as it’s been roughed up (I’ve seen wasps skin caterpillars), but fanpetals are the larval food of checkered-skippers. I’ve had this same species of wasp take small monarch caterpillars from my milkweed plants.

A couple more observations from the video, and a one that didn’t make it in

03:47 Here’s another Carolina mantis, but smaller than the first we saw and brown instead of green. According to an iNaturalist user, this is a “sub adult nymph.” iNaturalist doesn’t always include photos of insect nymphs and larvae, so I cross check IDs with a Google image search. Doing so, I found that Georgia mantis nymphs are able to change colors when they molt, based on their surroundings. They can be green, gray, or brown.

03:52 Another Poey’s furrow bee nectaring on turkey tangle fog fruit.

04:01 Another monarch caterpillar, hanging onto a leaf broken at the stem and angled downward. Older instar caterpillars do a thing where they chew the base of the stem until it just hangs down. They then climb down on to it and graze from the tip of the leaf. Maybe they’re less exposed this way? They’re also in similar pose as their “J” position, from which they make their chrysalis. Maybe this is a way of conditioning their bodies?

04:15 Scarlet rosemallow (Hibiscus coccineus), a native hibiscus flower.

The next one is one I edited out of the video. I had originally thought this was an assassin bug. An iNaturalist user suggested Acanthocephala terminalis, a leaf footed bug. So, instead of being a predatory insect, this is a sap sucking plant consumer. They are both in the suborder Heteroptera, the true bugs.

Apps and Citizen Science mentioned in the Backyard Blog

iNaturalist

Identify plants, animals, lichens, and fungi in your yard. Other users correct your identifications if you’re wrong, and even if they don’t, it can be a good springboard to further research.

Seek by iNaturalist

Instant identification, and it doesn’t record your location. This is a good option for kids with phones.

Monarch Larva Monitoring Project

Enter information about monarch caterpillars in your yard, and help researchers get a sense of the health of the monarch population that year, and how and when they’re migrating.

Great Sunflower Project

Record the number of pollinators visiting your flowers, and help researchers map pollinator activity across the country.