We’re less than a month away from EcoCitizen Day, and from PBS Nature’s American Spring LIVE (April 29, 30, and May 1 at 8 pm ET on WFSU-TV). Here’s a visit to one of our central locations for that event, which is a part of the Tallahassee/ Leon County City Nature Challenge. As you’ll see you should have plenty of wildlife to ID on iNaturalist on April 27…

EcoCitizen was made possible by a grant from PBS Nature, and is sponsored by the City of Tallahassee. Additional support has been provided by Leon County and Proof Brewing Company. EcoCitizen Day is a part of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s Tallahassee/ Leon County City Nature Challenge.

Subscribe to the WFSU Ecology Blog to receive more videos and articles about our local, natural areas, and subscribe to the WFSU Ecology Youtube Channel.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

On one visit to Lake Elberta, Peter directs the attention of a visiting group of children towards the peninsula. “Look, a wood stork!” He tells them, raising his binoculars. And then, “Never mind, it’s just trash.” It’s a moment that sums up bird watching here. Yes, there are endangered wood storks here fairly often, and many other species of interest. But there’s also a lot of garbage.

This is the conundrum of Lake Elberta. On the one hand, I can get video of all of these bird species in a small space conveniently located within a couple of miles of WFSU. On the other, the image is usually less than pristine. But there are people working to enhance this habitat, as we’ll see over the next couple of blog posts.

We’ve been shooting video here over the last few months, starting when we received a grant from the PBS show, Nature. They’re doing a live show about the coming of spring, called American Spring LIVE. Part of the grant was that we were doing videos on seasonal change. Another part of the grant has us hosting a large event for families, which is EcoCitizen Day on April 27. Since a lot of the action that day is focused on Lake Elberta, I thought it would be fun to see how the seasons changed here in the months leading up to the event.

It hasn’t been disappointing.

In one of the early meetings with our project partners, Florida Fish and Wildlife’s Peter Kleinhenz raved about this small park. In his other life as president of Apalachee Audubon, he applied for and received a grant from national Audubon to enhance this important urban habitat. We’ll look at what they’re doing in a second, and then go into the bird species we’ve seen here.

Peter Kleinhenz, President of Apalachee Audubon and an interpretive writer for Florida Fish and Wildlife.

Lake Elberta: Confounding Expectations

Peter spoke about Lake Elberta’s ability to confound expectations in the interview we shot for this video. “You have mowed grass, water that’s basically the dump water for FSU behind me.” Peter says. “You have trash around the lake.”

Lake Elberta is not a natural lake, but a retention pond built roughly twenty years ago. It collects stormwater runoff from Doak Campbell Stadium and its large parking lots, Gaines Street, and everything uphill to the north. Two ditches form a V to the south of the lake, carrying runoff from Cascades Park and Florida State University. These eventually connect to Munson Slough and then flow into Wakulla Springs.

Paved surfaces carry everything from lawn chemicals to the oil and exhaust that coat our roads. These chemicals collect in waterways next to paved surfaces. But don’t tell that to the wood storks that are constantly foraging for food in these ditches.

And mowed grass lawns don’t offer nearly as much habitat for insects as a more natural ground cover. Insects feed birds, and research shows that birds are suffering for a lack of native plants in urban areas. Yet you can see red-winged black birds, palm warblers, doves and more picking at the grass here to receive a meal.

So here’s this urban park, accessible by the Capital Cascades Trail and adjacent to a couple of south side neighborhoods. It’s not an ideal habitat, but there’s water and a good deal of plant life along the shores of the lake as well as a forested area along one of the ditches. So, as Peter tells me, it has the “core elements of habitat.” It’s a park with potential to be something special for the people in the area, and any Tallahasseeans who enjoy wildlife watching.

We’ll look at what Apalachee Audubon has been doing to enhance plant life around the lake in next week’s post. Today, we’re focusing on a couple of structures placed at opposite ends of the lake.

Making a Home for Purple Martins and Bluebirds

One Friday afternoon, a vanload of elementary school aged children rolled into Lake Elberta Park. Peter and his Apalachee Audubon interns and volunteers were going to put them to work.

The children, part of an after school program at the Walker Ford Community Center, were handed white plastic gourds to carry to the other side of the peninsula. There, they stuffed them with pine straw. The pine straw is supposed to look inviting to a nesting purple martin, a bird that will migrate here from South America in the spring to breed.

After they raised the gourds, Peter took the kids bird watching around the lake. This is where he mistook a white plastic bag for a wood stork. As someone who has scanned that shoreline for birds to video, I can attest that having bags and cans and bottles break up the pattern of plants can make you feel like you just spotted something living. And there was a wood stork somewhere in that vegetation, as well as a great egret and a great blue heron.

The question then becomes- will there be purple martins?

Soon after they raised the gourds, bluebirds started checking out this purple martin structure. In fact, in the one iNaturalist observation of bluebirds in the park was made right after the structure was raised. The photo on this observation even has the bluebirds right on the structure. That’s promising, as Apalachee Audubon installed bluebird boxes across the lake.

The iNaturalist app is at the heart of our EcoCitizen Day, and it’s a great tool for IDing any number of plant and animal species. But you need an image. And unless you have a camera with a good zoom lens, most birds are difficult to photograph. With that in mind, I checked eBird, a citizen science website and app from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. And to my surprise, I saw that purple martins were spotted, well, today (the day I started writing this post, March 26).

Edit April 1, 2019:

Of course we had to go get footage of these guys! Here is an image taken by EcoCitizen intern Nick Carlson on Friday, March 29. Additionally, a lot of flowers have started blooming since our last shoot here on March 6. We’ll keep coming back between now and EcoCitizen Day on April 27. It looks like we’ll have plenty to see and iNaturalize.

IDing birds | iNaturalist vs. eBird

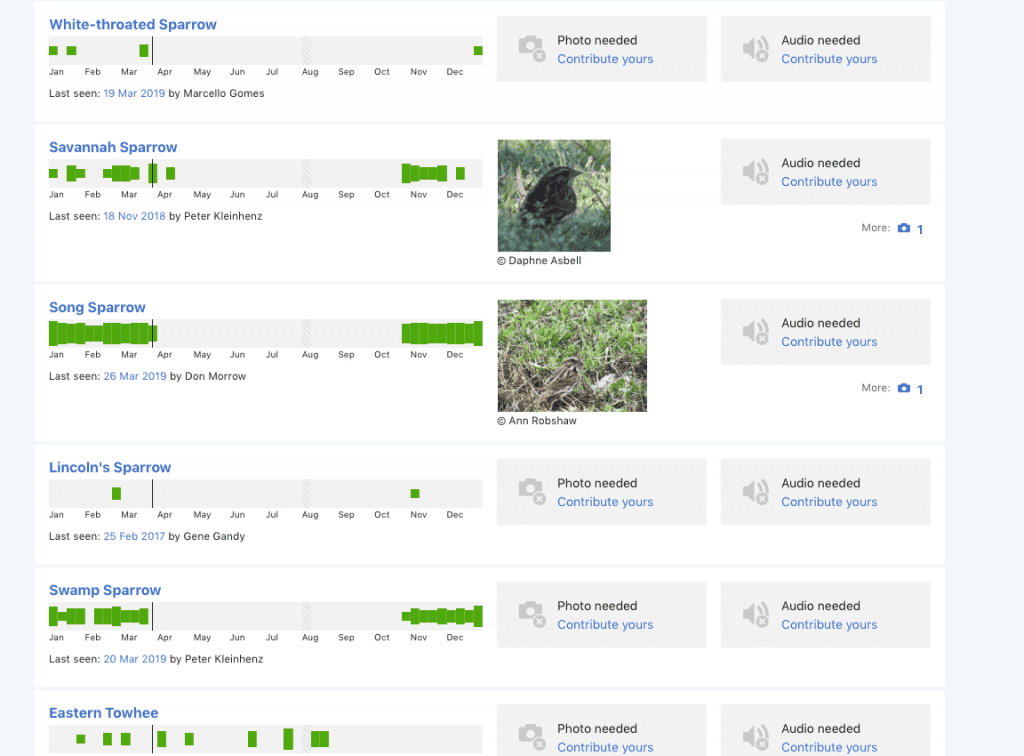

Both of these sites allow you to collect data about the natural world and share it with researchers, and the public. And this is handy. But each has different strengths and functionalities. As I review the birds we saw at Lake Elberta, I’ll link and refer to data from both. First, here’s a rundown of what each does:

iNaturalist

When I went to the iNaturalist site to get a sense of bird visitation at Lake Elberta, I had a little surprise. Most of the bird observations over the last few months were made by one person- me. Overall, the majority of the bird observations were made by a handful of people, spread over a few years.

iNaturalist is most easily used with a phone in our hands. I’ve observed my share of birds this way, but they’re not always great photos. Birds in trees are difficult; wading birds are at least a little bigger. You want to get a close photo for identification purposes, but you don’t want to disturb the bird.

I make most of my bird observations with a dslr camera with a 250 or 300 mm zoom lens. This requires me to remember the location where I took each photo, so I can geotag them later. iNaturalist does this automatically on your phone, and some cameras have this function as well. At a place like Lake Elberta or Cascades Park, it’s easy to find where I took a photo by looking at a map. It’s harder if you’re trying to remember a spot deep in the Apalachicola National Forest.

The advantage you get by using iNaturalist is that it’s pretty good at recognizing the species. And even if you get it wrong at first (was that a palm warbler or a yellow warbler?)- the iNaturalist community will usually know the answer. And not just on the great, close photos. In coming posts we’ll see how iNaturalist is ideal for observing plants and other animals.

eBird

You don’t need a photo to enter data on eBird. Many people do, and there are some beautiful ones on the site. The site is preferred by hard core birders, and they upload the lists birders have always made. This of course requires you to ID the birds on your own. I can ID most birds with my field guide, but it’s easier for me when I have a photo or two. Then, I can take my time and look at the pattern on the wing, or the length of the beak.

And there’s no reason you can’t do both eBird and iNaturalist. That requires you to take those good photos, upload them to iNaturalist, and then make a list for eBird. Why do this?

eBird does some great things with its data. There are way more bird observations on eBird than iNaturalist. And when I click on an eBird hotspot for a location, and then click on a bird species name, I get data for that species at the location. For instance, there have been 14 purple martin observation at Lake Elberta over the years. They have arrived as early as February and been observed in Late June, though the bulk of the observations have come between April and early June.

This is presented in a handy little chart. I like this, because Lake Elberta is a destination for migratory birds throughout the year. Consulting these charts, I can predict more or less when I might see a redhead duck or a northern shoveler. By entering observations year after year, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology can track migrations over time. And this is important, as changing climates can affect migration times, and a host of other seasonal events.

But they can’t do that if we don’t make the observations.

Birds We See in the Video | Lake Elberta Through the Seasons

Wood Storks in the ditch.

00:03 We see several shots of wood storks (Mycteria americana) to open the video. They’re in the ditch on the west side of the park, which carries water from FSU. You can see visible trash in the ditch, but the real concern is the cleanliness of the water.

Three wood storks (Mycteria americana) . The two on the left are adults, the one on the right is a juvenile.

00:22 Here we see two wood storks (in the video I mean. For the purposes of the blog, I liked this image I took just before that showing the three). The one that takes off and leaves the frame is an adult, the other is a juvenile. You can tell the younger stork by the grey feathers on the back of its head. Mature wood storks have black, scaly heads. Combine that with their height- about as big as a great blue heron- and that’s one striking bird.

A closer look at the juvenile wood stork (Mycteria americana). You can identify it as such from the light grey feathers on its neck and head.

I observed these storks, and entered them on iNaturalist, on November 8, 2018. eBird lists 483 wood stork observations at Lake Elberta, and they’re pretty much here year round. The exception is late May through most of June, which coincides with the time when wood stork chicks hatch. It makes sense that adults would stay closer to their rookeries at this time of year (we visited a wood stork rookery last year- look for that story after our EcoCitizen special on May 30).

00:30 A great blue heron (Ardea herodias) sits atop the rusty pipe. Below it are two wood storks (the juvenile is at the left), and a great egret (Ardea alba). I stumbled upon this richness of wading birds by following a belted kingfisher that was a little too quick for me to photograph.

Here the action moves away from the ditch and to the lake.

00:35 Double crested cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus) on a sandbar off of the peninsula in Lake Elberta.

A peninsula juts out to the center of the lake, and is a center of activity here. Cormorants are one of the more common birds at the lake, with 749 observations on eBird. There is an absence of them in June, like the wood stork, and likely for the same reason (The wood stork rookery we visited had plenty of nesting cormorants).

00:40 Three blue-winged teals (Spatula discors) forage in the water next to a mat of mud and garbage, with a killdeer (Charadrius vociferus) at the center in the foreground. Three sandpipers I didn’t identify are foraging to the right.

This October 25 observation of the teals was one of my first on iNaturalist, and it was one of the first times I saw its usefulness in identifying species. The males of this species become more distinctive when they get their breeding plumage in November. What we see here are either females, nonbreeding males or some combination. And there are many duck species whose females look similar. So I picked the genus Spatula, based on the app’s suggestion. Three users suggested blue-winged teal, Spatula discors. Pretty neat the way that worked.

This is one of many migratory ducks that visit Lake Elberta. The bulk of eBird observations have come between March and early May, with a little burst in October and again in November. Since I never saw them again, it could be that these ducks were stopping on the way to another destination, like the St. Marks Refuge, which would account for the shorter windows of their fall visits as we see them in the graph.

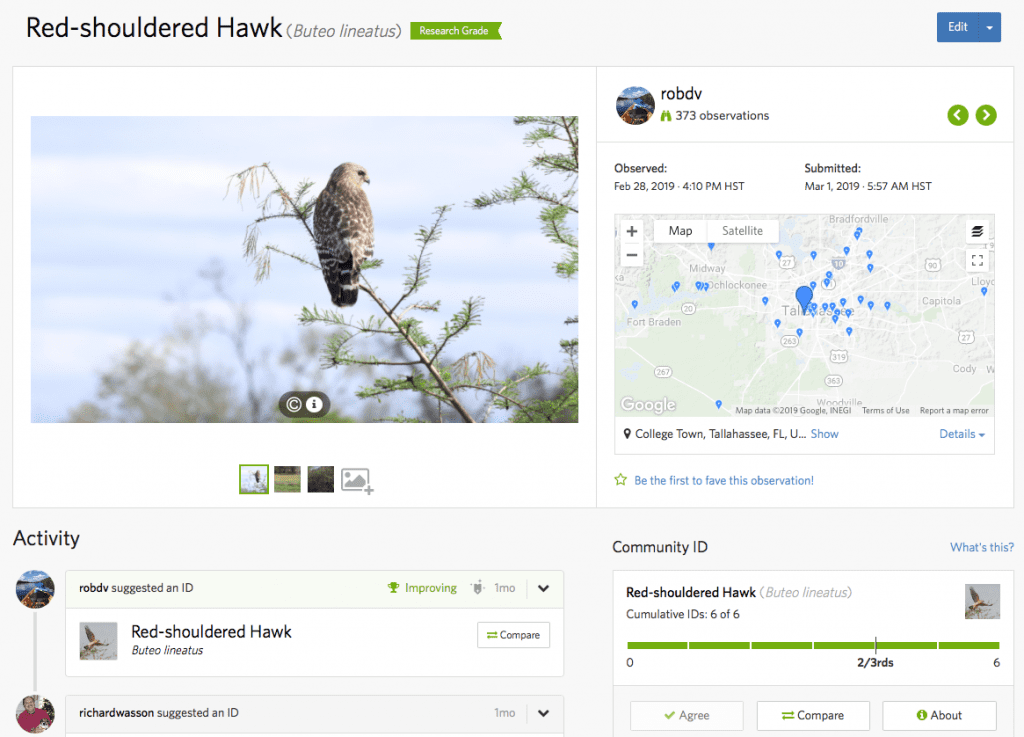

00:42 Red shouldered hawk (Buteo lineatus) perched on a tree overlooking the lake. Some people have trouble telling apart the hawks of the Buteo genus- iNaturalist could be of help here. I was fairly certain when I chose that as the species, and 5 other users verified it.

01:05 Common slider (Trachemys scripta) on a culvert. You never know what temperatures we’ll get in January in Tallahassee, and January 17 was warm enough for turtles to be out and about.

Migratory Ducks at Lake Elberta

This lesser scaup (Aythya affinis) never came close to the shore, so I cropped this image from a larger one, and submitted it to iNaturalist.

01:30 Over thirty ducks floating, mostly lesser scaup (Aythya affinis). We shot these on the day we interviewed Peter, March 6. But I first made an iNaturalist observation of this species here on November 29. eBird shows them as a constant presence at Lake Elberta from Late October through April.

01:33 A combination of ducks species (bottom of screen) and cormorants (top of screen). On the right side of the screen, you see three redheads and, in the lower right corner, a bufflehead.

01:35 Redhead (Aythya americana). I observed this on March 6 as well. Peter mentions them only recently having arrived at Lake Elberta. While eBird shows them as visiting most often between December and April, the greatest number of observations fall in March.

01:45 Canada geese (Branta canadensis) land in the middle of the redheads. Around early March, you see geese getting feisty and honking a lot. Their nesting season was about to begin, and since that day, I have seen a nesting goose or two around town.

Other migratory birds, and some residents, at Lake Elberta

01:50 Eastern phoebe (Sayornis phoebe). This bird is fairly common in Tallahassee during the fall and winter. The 402 eBird observations start in October and run through mid-April. I’ve made a few eastern phoebe observations on iNaturalist, including one on my phone (it can be done). They’re pretty much everywhere here in town. The phoebes I was shooting that October day were hopping around a bit, but when they perch, they kind of wag their tails.

Long-tailed skipper (Urbanus proteus) on a pink flower. Seeing the bean pods around it, and knowing that these butterflies’ caterpillars eat bean plants, I wonder if we’re not looking at its host plant.

01:57 Long-tailed skipper butterfly (Urbanus proteus) on what might be a tievine flower. I observed a couple of long-tailed skippers here, the last on October 17. I marked an iNaturalist observation for the flower, taking its suggestion of tievine (Ipomoea cordatotriloba), but no one ID’d it. Birds and butterflies, most insects really, get ID’d by other iNat users, but plants can be more challenging. By the way, you can raise long-tailed skippers at home, if you don’t mind your bean plants getting a little torn up.

02:01 Northern mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos)

02:02 Northern cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis). We shot this in January, and you can see how the vegetation at the water’s edge has thinned.

02:06 Bufflehead (Bucephala albeola). These ducks are a constant presence at Lake Elberta in the fall in winter. Their eBird chart shows them arriving in November and staying through April.

02:12 Two bufflehead diving.

02:16 Northern shovelers (Spatula clypeata). When they’re swimming in profile, you can see where they get their name- their large, shovel shaped bills. They visit starting around mid-October and leave by mid-April.

02:18 Yellow-rumped warbler (Setophaga coronata). Not only is this one of the more common migratory birds at Lake Elberta, with 562 eBird observations between October and early May, but it’s one of the warblers you’re most likely to see in our area at that time of year. These and palm warblers are regular winter visitors to my bird feeder.

02:21 Spotted sandpiper (Actitis macularius). Its 93 eBird observations at Lake Elberta come in waves lasting a few weeks, starting in September and running though late May. It doesn’t appear that they stay in one place for very long. I love the way they wiggle their tail feathers.

03:15 Red-winged blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus) foraging in the grass. These appear to all be females, who are brown and streaked. They constantly confounded our EcoCitizen intern, Nick, who thought he was entering a sparrow into iNaturalist, only to be told it was a red-winged blackbird that was neither black nor red.

03:18 Cormorant swimming in the ditch.

03:22 Great egret walking along the trash strewn peninsula.

03:28 Killdeer on the mowed grass.

03:34 Anhinga (Anhinga anhinga) with a nice fish meal. Commonly called snake birds, they swim with their bodies mostly submerged, only their snake like necks visible. They spear fish with those pointy beaks, and they flip the fish into their mouths.

03:42 We close the segment with a shot of a honey bee on Bidens alba. This sets up our next segment, where Apalachee Audubon enhances the plant life around Lake Elberta.

WFSU EcoCitizen is funded by Nature, a production of THIRTEEN PRODUCTIONS LLC for WNET and PBS. American Spring LIVE is a production of Berman Productions, Inc. and THIRTEEN PRODUCTIONS LLC for WNET.

Major support for Nature: American Spring LIVE was provided by the National Science Foundation and Anne Ray Foundation.

Additional financial support was provided by the Arnhold Family in memory of Henry and Clarisse Arnhold, Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III, the Kate W. Cassidy Foundation, the Lillian Goldman Charitable Trust, Kathy Chiao and Ken Hao, the Anderson Family Fund, the Filomen M. D’Agostino Foundation, Rosalind P. Walter, the Halmi Family in memory of Robert Halmi, Sr., Sandra Atlas Bass, Doris R. and Robert J. Thomas, Charles Rosenblum, by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by the nation’s public television stations.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1811511. Any

opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and

do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.