As David & co. start their new research on the Apalachicola oyster fishery crisis, He and Randall (and their colleagues in Georgia and North Carolina) are starting to wrap up the NSF funded oyster study that we have been following over the last couple of years. Over the next few weeks, we’ll take a look back at that research through a series of videos. We’ll cover some oyster basics (how does an animal with no brain behave?), explore David and Randall’s ideas on the role of fear on the oyster reef (what makes a mud crab too afraid to eat an oyster?), and see the day-to-day problem solving and ingenuity it takes to complete a major study. As these videos are released, we’ll also keep tabs on the work being done in Apalachicola Bay, in which many of the same methods will be used.

Dr. David Kimbro FSU Coastal & Marine Lab

After all, nutrients are basically plant food and oysters are animals. And how could too few nutrients coming down with the trickling flow of the Apalachicola River possibly explain the record low number of Apalachicola oysters?

After all, nutrients are basically plant food and oysters are animals. And how could too few nutrients coming down with the trickling flow of the Apalachicola River possibly explain the record low number of Apalachicola oysters?

This is the perfect time to use the favorite idiom of my former mentor Dr. Ted, “The long and the short of it is….”

The short of it: Plants love nutrients and sunlight as much as I like pizza and beer. But unlike my favorite foods, these plant goodies make plants grow fast and strong. This works out well for us because we all need nutrients for basic body functioning, and because we get them by eating plants and/or by the eating animals that previously consumed plants.

For our filter-feeding bivalve brethren, they get nutrients and energy by eating plant-like cells (phytoplankton) that float in the water. So, it is possible that the trickling flow of the Apalachicola River is bringing too few nutrients to support the size of the pizza buffet to which the Apalachicola oysters are accustomed. But this idea has yet to be tested.

The long of it: Long before the flow of the Apalachicola River slowed to a trickle, there weren’t a lot of nutrients. That’s why the numbers of humans used to be so low: too few nutrients meant too few plants and other animals for us to eat.

How could this possibly be the case given that 78% of the air we breathe is made up of a very important plant nutrient, nitrogen? And there is a lot of air out there!

Well, only a precious few plants exist that can deal with the nitrogen in our air and these are called nitrogen-fixers. Think of these as single-lane, windy, and bumpy dirt roads. In order to help create a plant buffet for all of us animals, a lot of atmospheric nitrogen (bio-unavailable) has to travel down this very slow road that the n-fixers maintain. As a result, it naturally takes a long time for the land to become fertile enough for a large buffet. And, it only takes a couple of crop plantings to wipe out this whole supply of bio-available nitrogen that took so long to accumulate.

Turns out that the ancient Inca civilization around Peru was not only lucky, but they were also pretty darn smart. Lucky, because they lived next to coastal islands that were basically big piles of bird poop, which is very rich in bio-available nitrogen. I’m talking thousands of years of pooping on the same spot! Smart, because they somehow figured out that spreading this on their fields by-passed that slow n-fixing road and allowed them to grow lots of food. Once Columbus tied the world together, lots of bird poop was shipped back to European farms for the same reason. That’s when the European population of humans sky-rocketed.

Turns out that humans in general are pretty smart. Through time, some chemists figured out how to create artificial bird poop, which we now cheaply dump a lot of on our farming land. So, in these modern days, we are very, very rich in bio-available nutrients.

Where am I going with the long of it? Well, on the one hand, these nutrients wash off into rivers and then float down into estuaries. This is how the phytoplankton that oysters eat can benefit from our solution to the slow n-fixing road. In turn, oysters thrive on this big phytoplankton buffet.

But, on the other hand, too much of these nutrients flowing down into our estuaries can create big problems. Every year, tons of nutrient-rich water makes it way down the Mississippi and into the shallow Gulf of Mexico waters. There, this stuff fuels one big time buffet of phytoplankton, which goes unconsumed. Once these guys live their short lives, they sink to the bottom and are broken down by bacteria. All this bacterial activity decreases the oxygen of water and in turn gives us the infamous dead zone. Because nutrient-rich run-off continues to increase every year, so too does the dead zone.

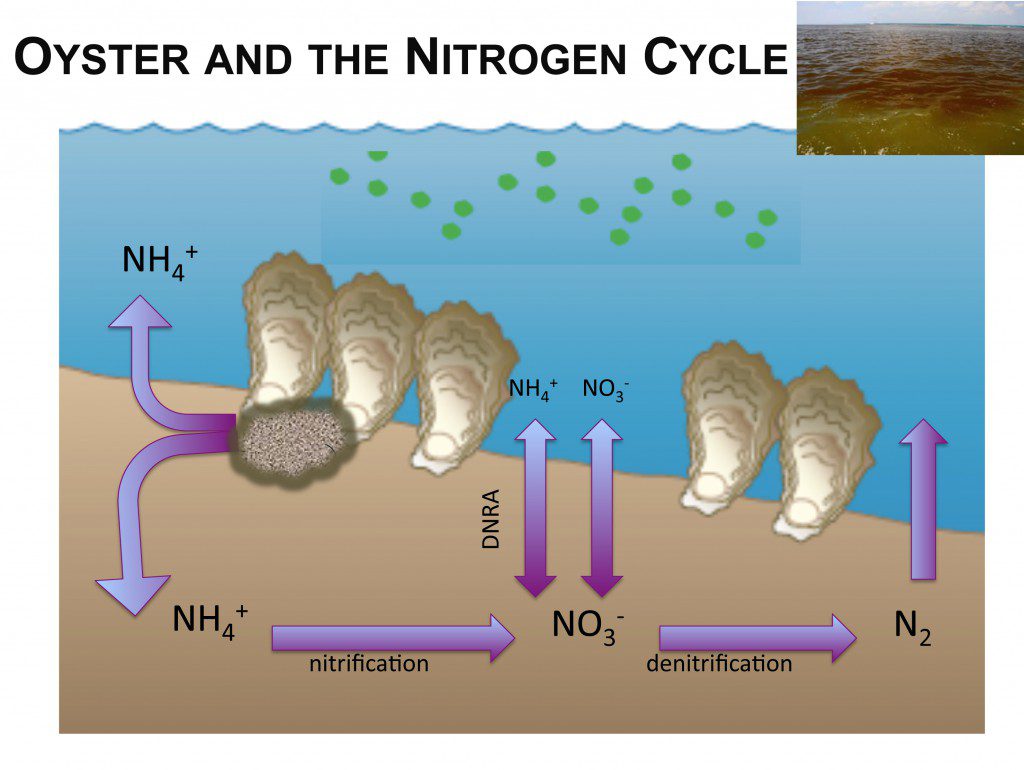

I’ll close with the thought that oysters themselves may help keep the phytoplankton buffet from getting out of control by acting like anti-nitrogen fixers. In other words, they may help convert an excess of useable nitrogen back into bio-unavailable nitrogen. While this might not have been a great thing to have in low nutrient situations, we currently live in a nutrient-rich era. What’s even cooler is that it all has to do with poop again! But this time, we are talking oyster poop.

Dr. Mike Piehler, presenting to his collaborators Dr. Jeb Byers (Right), Dr. Jon Grabowski (reclined on couch), Dr. Randall Hughes and Dr. David Kimbro (out of frame). These five researchers have worked on oyster reef ecology since their time at the University of North Carolina. Three years ago, the National Science Foundation funded research into their ideas about predators and fear on oyster reefs.

So does this really happen? Yes. Check out an earlier post for the details. But we don’t fully understand it and that’s why it is a major focus of our research. Our collaborator, Dr. Michael Piehler of UNC-Chapel Hill, is leading this portion of our research project. Read more of Dr. Piehler’s work on this topic here.

So, hopefully this post explains why the relationship between nutrients and oysters is not so simple. But it sure is interesting and a worthy thing to keep studying!

Cheers,

David

In the Grass, On the Reef is funded by the National Science Foundation.

3 comments

Thanks for “breakin’ this down” to my layperson’s level Dr. K. This is the first time I fully understood the Nitrogen cycle!

Hi Robin,

you are most welcome, and thanks for following the blog!

Best,

David

[…] Donate Skip to content HomeThe ScienceThe “In the Grass, On the Reef” Master PlanCoastal Habitat Quick DictionarySalt MarshIn the Grass- Salt Marsh Biodiversity StudyMeet the Species “In the Grass”Oyster ReefOn the Reef- The Biogeographic Oyster StudyMeet the Species “On (and swimming around) the Reef”Watch Oysters GrowJacksonvilleSaint AugustineAlligator HarborSeagrass BedPredatory Snails, and Prey, of Bay Mouth BarIn the Grass, On the Reef DocumentaryEcoAdventures North FloridaEcoAdventures HomeActivitiesPaddlingHikingBird/ Wildlife WatchingArt/ PhotographyHistory/ ArcheologyApalachicola River and Bay Basin ← What’s the deal with nutrients and oysters? […]

Comments are closed.