For today’s post, we shift our look at the ecology of fear from oyster reefs to the (often) neighboring salt marsh. We know crown conchs are villains on oyster reefs, but might they redeem themselves “in the grass?” If they live on the Forgotten Coast, it depends on what side of Apalachicola they live.

Dr. Randall Hughes FSU Coastal & Marine Lab

If you’re a fan of oysters and you read David’s previous post, then you probably don’t like crown conchs very much. Why? Because David and Hanna’s work shows that crown conchs may be responsible for eating lots of oysters, turning previously healthy reefs into barren outcrops of dead shell. And we generally prefer that those oysters be left alive to filter water and make more oysters. And, let’s be honest, we would rather eat them ourselves!

If you’re a fan of oysters and you read David’s previous post, then you probably don’t like crown conchs very much. Why? Because David and Hanna’s work shows that crown conchs may be responsible for eating lots of oysters, turning previously healthy reefs into barren outcrops of dead shell. And we generally prefer that those oysters be left alive to filter water and make more oysters. And, let’s be honest, we would rather eat them ourselves!

But, in something of a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde act, crown conchs can take on a different persona in the salt marsh. Here, the exact same species acts as the good guy, increasing the abundance of marsh cordgrass. And more abundant marsh plants generally means more benefits for we humans in the form of erosion control, water filtration, and habitat for the fishes and crabs we like to eat. How exactly does that work?

If you look out in a salt marsh in much of the Gulf and Southeast Atlantic, I can nearly guarantee that you’ll see a marsh periwinkle snail. Usually, you’ll see lots and lots of them. These marine snails actually don’t like to get wet – they climb up the stems of the marsh grass as the tide comes in. While they are up there, they sometimes decide to nibble on a little live cordgrass, creating a razor blade-like scar on the plant that is then colonized by fungus. The periwinkles really prefer to eat this fungus instead of the cordgrass, but the damage is done – the fungus can kill the entire cordgrass plant! So these seemingly benign and harmless periwinkles can sometimes wreak havoc on a marsh.

But wait a minute – if periwinkles cause all the cordgrass to die, then why do you still see so much cordgrass (and so many snails) in the marsh? That’s where the crown conch comes in.

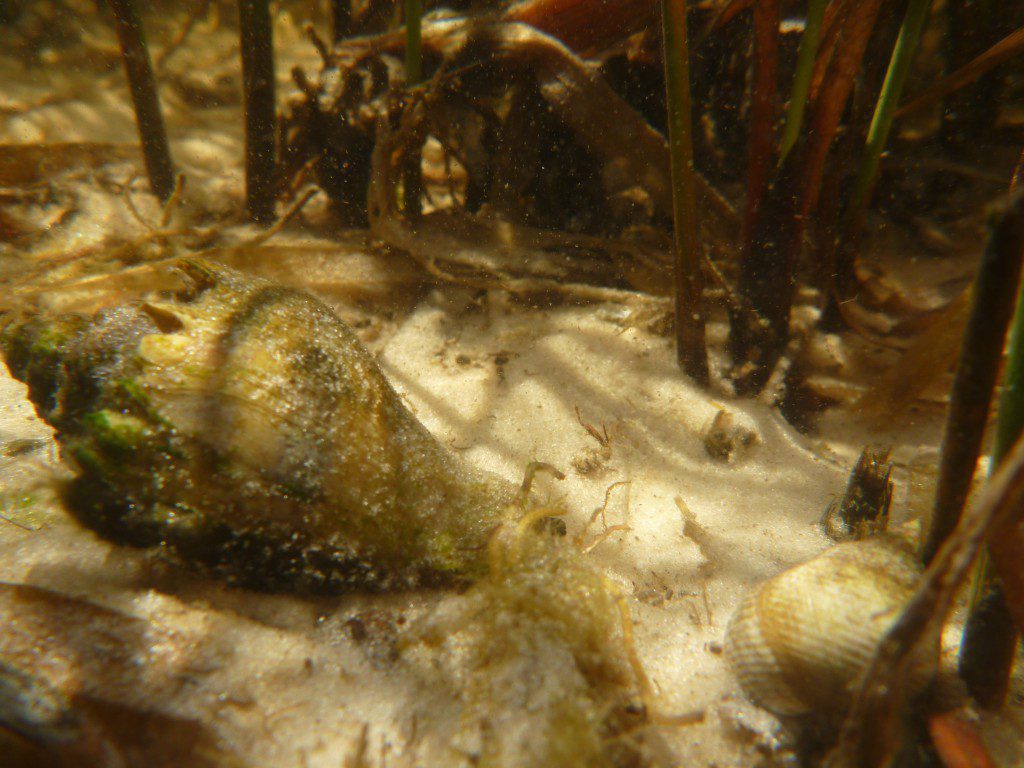

At the edge of a marsh at high tide, a crown conch approaches a periwinkle snail. As shown in the video above, the conch was soon to make contact with the smaller snail and send it racing (relative term- the video is of course sped up) up a Spartina shoot.

In marshes along the Gulf coast, there are also lots of crown conchs cruising around in the marsh (albeit slowly), and they like to eat periwinkles. Unlike other periwinkle predators such as blue crabs, the crown conchs stick around even at low tide. So when the periwinkles come down for a snack of benthic algae or dead plant material at low tide, the crown conchs are able to nab a few, reducing snail numbers. And fewer snails generally means more cordgrass.

Of course, the periwinkles aren’t dumb, and they often try to “race” away (again, these are snails!) when they realize a crown conch is in the neighborhood. One escape route is back up the cordgrass stems, or even better, up the stems of the taller needlerush that is often nearby. By causing periwinkles to spend time on the needlerush instead of grazing on cordgrass, or by making the periwinkles too scared to eat regardless of where they are sitting, the crown conch offers a second “non-consumptive” benefit for cordgrass. One of our recent experiments found that cordgrass biomass is much higher when crown conchs and periwinkles are present compared to when just periwinkles are present, even though not many periwinkles were actually eaten.

On the other hand, if the periwinkles decide to climb up on the cordgrass when they sense a crown conch, and if they aren’t too scared to eat, then crown conchs can actually have a negative effect on the plants. This is exactly what David found in one of his experiments. In this case, the tides play an important role – west of Apalachicola, where there is 1 high and 1 low tide per day, each tide naturally lasts longer than east of Apalachicola, where there are 2 high tides and 2 low tides per day. The longer tides west of Apalach appear to encourage the snails not only to stay on the cordgrass, but also to eat like crazy, and the plants bear the brunt of this particular case of the munchies.

On the other hand, if the periwinkles decide to climb up on the cordgrass when they sense a crown conch, and if they aren’t too scared to eat, then crown conchs can actually have a negative effect on the plants. This is exactly what David found in one of his experiments. In this case, the tides play an important role – west of Apalachicola, where there is 1 high and 1 low tide per day, each tide naturally lasts longer than east of Apalachicola, where there are 2 high tides and 2 low tides per day. The longer tides west of Apalach appear to encourage the snails not only to stay on the cordgrass, but also to eat like crazy, and the plants bear the brunt of this particular case of the munchies.

So even in the marsh, it turns out that crown conchs can be both a friend and a foe to marsh cordgrass, depending on how the periwinkles respond to them. And figuring out what makes periwinkles respond differently in different situations just gives us more work to do!

Music in the piece by Revolution Void.

In the Grass, On the Reef is funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

1 comment

[…] (or harvest oysters) know that crown conchs can become a real nuisance on oyster reefs (though a potential benefactor of the equally productive salt marsh system). A crown conch fishery would provide some income for […]

Comments are closed.