Dr. David Kimbro FSU Coastal & Marine Lab

Why are we on oyster reefs?

Well, I am broadly interested (and hope to make you interested) in how large predators can help protect important habitats like oyster reefs by preventing smaller animals from eating all the oysters. I’m sure you can agree that we don’t need anything competing with people to eat oysters! It’s also important to keep enough oysters on the reef to filter water and provide habitat for lots of fishes and invertebrates, because these processes help keep estuaries healthy, and healthy estuaries support critical economic and recreational activities along our coastline.

Well, I am broadly interested (and hope to make you interested) in how large predators can help protect important habitats like oyster reefs by preventing smaller animals from eating all the oysters. I’m sure you can agree that we don’t need anything competing with people to eat oysters! It’s also important to keep enough oysters on the reef to filter water and provide habitat for lots of fishes and invertebrates, because these processes help keep estuaries healthy, and healthy estuaries support critical economic and recreational activities along our coastline.

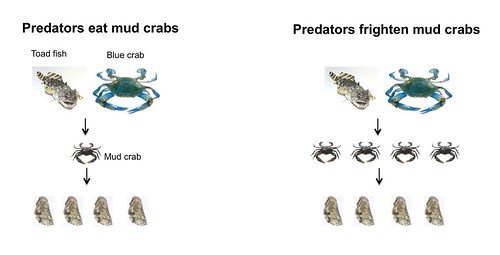

Because 90% of the oyster reefs in the world were either eaten (they taste really good) or dredged away (they are a pain for boats to get around), we are specifically studying whether predator-prey interactions determine how the remaining 10% of our oyster reefs operate. For example, it turns out that large predators such as fish and big crabs can protect oysters either by eating the smaller snails and crabs that consume the oysters or by scaring the snails and crabs enough to spoil their appetites for oysters.

Why should it matter whether the large predators eat or frighten the smaller predators, as long as the oysters don’t get eaten? Since oysters are sessile, they can’t run away from their predators, but they can stop filtering water when predators are around in order to avoid producing a signal that can give away their location. So if there are lots of oyster predators around, even if they are scared and not actually eating oysters, they may still keep oysters from filtering water. And, the amount of water oysters filter matters, because filtration can remove excess nutrients from the water, helping to prevent algal blooms and low oxygen conditions in coastal waters (bad for fish and other animals). This potential link between predators and nutrient cycling and whether it operates the same way in different places is why myself and researchers from the University of Georgia, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and the Gulf of Maine Research Institute are out studying reefs from Florida to Virginia.

If we can understand why more oysters survive in certain locations and how these oysters affect nutrient cycling differently in different locations, then we can better target our restoration dollars when trying to recover the other 90% of our oyster reefs, thereby getting the biggest bang for our buck.

We’re just getting started. And as you can see from the photos and videos, it’s a slow and ungraceful process at first!

David’s research is funded by the National Science Foundation.

4 comments

I have followed this work for some time. I think these projects are very important for the overall understanding of benthic ecology – and not just for oyster reefs. Obviously, oysters provide a biogenic habitat AND countless ecosystem services, but other bivalves are similarly affected by these interactions – some which are important economically and others which are more important ecologically. Keep up the good work, I look forward to reading more about this work.

[…] Gulf oyster reefs retain their abundance and quality. When we accompanied David Kimbro on the first day of his study in Alligator Harbor, the scientist who had been studying reefs in North Carolina and […]

[…] a major part of this study, and david is happy to get started on it just five months after that first day in Alligator Harbor. And it’s still early enough in this three year study that they can tweak the experiment […]

[…] (described in detail by David earlier) to kick off year two. It’s a far cry from last May,when we saw David, by himself, figure out how he was even going to get to the sites. He and his crew are […]

Comments are closed.