Dr. Randall Hughes FSU Coastal & Marine Lab

As David has mentioned previously, predators can affect their prey by eating them (a very large effect to the prey individual concerned!) or by changing their behavior. And exactly how the prey change their behavior can have large consequences for the things that they eat. For instance, if you’re out camping and hear a bear lumbering around, do you quickly pack up all your food and put it out of reach of the bear and yourself? Or do you quickly eat as much as you can?

As David has mentioned previously, predators can affect their prey by eating them (a very large effect to the prey individual concerned!) or by changing their behavior. And exactly how the prey change their behavior can have large consequences for the things that they eat. For instance, if you’re out camping and hear a bear lumbering around, do you quickly pack up all your food and put it out of reach of the bear and yourself? Or do you quickly eat as much as you can?

This summer we worked with Kelly, an undergraduate from Bridgewater College, to document how mud crabs deal with this dilemma of getting enough to eat but not getting eaten themselves.

Specifically, we wanted to know how they respond to the presence or absence of catfish, and how this response affects the survival of juvenile oysters. Sounds straightforward, right? Well, yes, in concept, but as Kelly quickly discovered, putting that “on paper” concept into reality at the lab took a lot of time and effort!

First, she had to get the “mesocosms” (aka large tubs) ready to serve as adequate habitat for the crabs, with plenty of sand and dead oyster shell for them to hide in.

Next, Kelly took individual juvenile oysters, or “spat”, and used a marine adhesive to attach them to small tiles that we could distribute among all of the mesocosms.

Juvenile oysters attached with Zspar (a marine adhesive) to a tile so we could assess mud crab predation.

You may have noticed that I mentioned catfish, and that these mesocosms are not particularly large relative to the size of a catfish. Never fear – because we wanted to separate the effects of catfish cues from the effects of catfish actually eating mudcrabs, the catfish were kept in a much larger tank, and then water from this tank was pumped into the mesocosms receiving catfish cues. (Setting up the pump and tubing to 60+ tanks was a several-day effort in itself!)

Once everything was in place, it was time to collect the mud crabs. We couldn’t collect the crabs gradually, because they like to eat each other when confined in small spaces in the lab, so we garnered as much help as we could and held our own little mud crab rodeo. (And got caught in quite a thunderstorm in Alligator Harbor, but that’s another story).

Finally, it was time to start the experiment! We measured the size of each of the mud crabs, added them to the mesocosms, and let them eat (or not). Each day, Kelly would count the number of live oysters remaining, and she would remove a few mud crabs from some of the mesocosms to simulate catfish predation. There were a lot of moving parts to this experiment, and Kelly did a great job managing it!

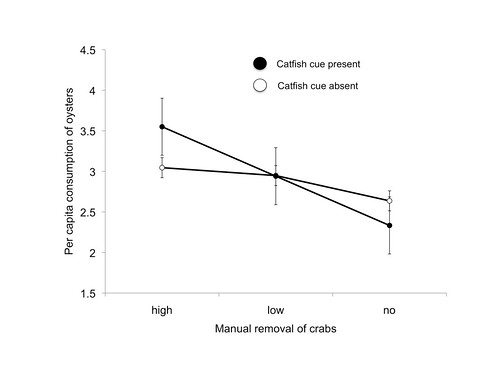

And what did we find? Turns out that individual mud crabs actually eat more juvenile oysters when they are exposed to catfish cues and the removal / disappearance of some of their neighboring mud crabs, compared to just the removal of neighboring mud crabs or the absence of catfish cues. But overall, the the removal of mud crabs have a positive effect on oyster survival. (Even though individual crabs may eat more, there are not as many crabs around, so it’s a net positive for oysters.)

Mud crabs ate more oysters per individual in buckets with exposure to catfish cues and high rates of manual removal of mud crabs (to simulate predation).

Kelly has returned to classes, so we’ve now recruited a new assistant, Meagan, to help us with an experiment to address the additional questions that inevitably arise as you learn more about a system – for example, do mud crabs behave differently if catfish are around all the time versus only some of the time? We’ll keep you posted…

3 comments

Wow, quite the set-up! I am jealous of that space!

Interesting results too – curious, do you think the difference between the high crab removal and no crab removal in regards to the catfish cues has something to do with competition for space? Not knowing anything about the crab behavior in your set-ups, it looks like maybe when you maintained mud crab density with the catfish cue present, maybe they spent more time interacting with each other – my guess is looking for hiding spots – than eating, leading to your observed effect?

As a side question, how did you pump the cue water to all your tubs, a peristaltic pump? Was it just gravity? Seems like quite the complicated set-up

Hi John,

We do think there are some intraspecific interactions among the crabs (competition for hiding spaces, general antagonism – they are feisty!, etc) that are contributing to the lower per capita feeding rate at higher crab density. We’re following up on that now.

We are lucky to have plenty of tank space, as well as the staff member (Bobby Henderson) who designed our pump apparatus! It’s a submersible sump pump with a manifold attached that has individual outlets for each of the tanks receiving fish cues. It’s even more impressive for the current experiment – I’ll be sure to get a good pic to share.

[…] Excerpts from a comment on Randall’s September 28th post, Scared Hungry. Read the whole comment here. […]

Comments are closed.