On last week’s EcoCitizen adventure, we saw how Apalachee Audubon has been working to create a healthy pollinator habitat around Lake Elberta by adding hundreds of native plants.

We’re about two weeks away from EcoCitizen Day, where you can observe wildlife at Lake Elberta and in the Munson Sandhills. We’re also just over two weeks away from PBS Nature’s American Spring LIVE (April 29, 30, and May 1 at 8 pm ET on WFSU-TV). EcoCitizen was made possible by a grant from PBS Nature, and is sponsored by the City of Tallahassee. Additional support has been provided by Leon County and Proof Brewing Company. EcoCitizen Day is a part of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s Tallahassee/ Leon County City Nature Challenge.

Subscribe to the WFSU Ecology Blog to receive more videos and articles about our local, natural areas, and subscribe to the WFSU Ecology Youtube Channel.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

It ended up being more climbing than I thought I’d be doing on a college campus shoot. I thought, today we’ll see a different way to use iNaturalist than we’ve been highlighting. Instead of going into the forest, or a city park, we’d be searching manicured lawns around classroom buildings. Or the edges of parking lots. But what the Florida A&M University BioBlitz showed me was much more interesting.

“This is an urban campus.” says Dr. Kathryn Ziewitz, Executive Director of FAMU’s Sustainability Institute. “A lot of people think that it’s devoid of nature, and that’s simply not the case.”

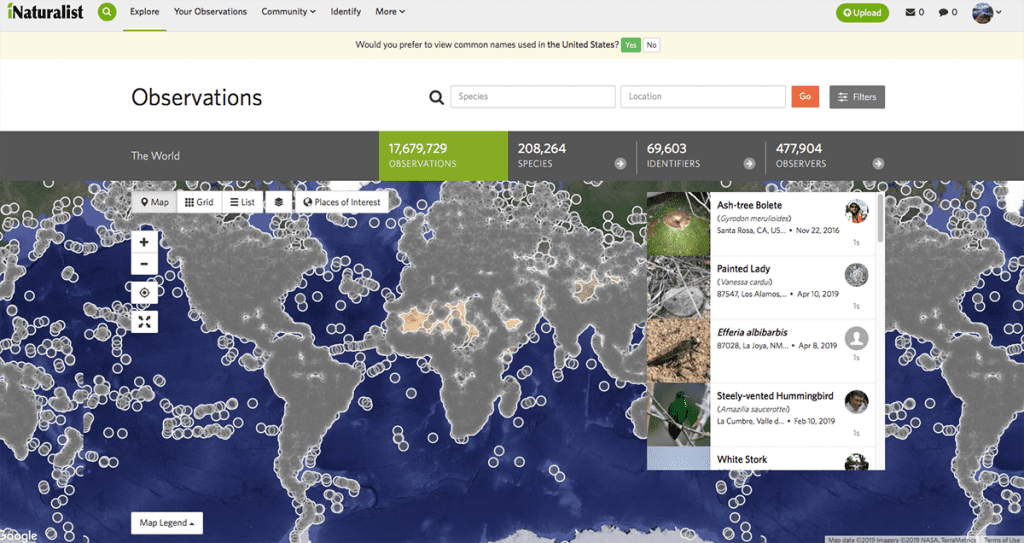

Kathryn coordinated the BioBlitz with the FAMU GeoSpatial Club. These are students studying Geographic Information Systems, or GIS. GIS combines maps and data, like the iNaturalist app does. When you make a photo observation with iNaturalist, that photo and the species information are tagged to a location. Now you have a single piece of data for that spot. The power of the app comes from all of our observations together; a map thick with pinpoints, showing plants and animals living around the world.

Today, we’re collecting plant and animal data on the Florida A&M campus. So we’ll then have this information, but who’ll use it? And for what purpose? Many people don’t like to call iNaturalist a citizen science app, because, while ordinary citizens are collecting the information, they’re not doing so to answer a specific scientific question.

However, researchers have set up projects within iNaturalist to answer their questions, or to map certain species. Depending on what we find, or where we find it, we might be aiding one of those efforts. Roaming the wilder parts of FAMU’s campus, I can see the potential for one or two such projects.

The Parking Lot and Lawn Ecosystems

The day starts about how I expect. Kathryn addresses the BioBlitzers, a combination of students and experienced biologists. Tall Timbers ornithologist Jim Cox is here to lead a group to a retention pond at the center of campus. Another group is going to FAMU’s garden on Orange Avenue. I’ve often driven by the garden over the years, and I’m interested in checking it out. But a third option sounds the most intriguing- a “forested” area on the south end of campus.

Kathryn’s in this group, as is our EcoCitizen collaborator, FWC’s Peter Kleinhenz. Peter’s a herpetologist, and much like on our adventure at L. Kirk Edwards WEA, he’s turning over logs in search of salamanders and other creepy crawlies. Well, there it was logs. Here it’s railroad ties being used as parking blocks.

He turns one over. Cockroaches scurry away, and millipedes either curl up or start digging.

It’s mid-February, and there is an interesting variety of flowers starting to grow in and around the grass. Kathryn snaps a photo of Bidens alba, which, as we covered last week, has stayed in bloom all throughout a warm winter. “One of the students that took part remarked ‘oh, I thought these were just weeds,'” Kathryn says. But because it grows like a weed, and blooms perennially, it’s a consistent source of nectar for pollinators.

We find a lot of other flower species to upload to iNaturalist. I snap a photo of a flower called black medick, which is non-native. Someone else uploads a photo of a pretty blue flower called bird’s-eye speedwell, which turns out to be another non-native. The grass around this parking lot has a lot of the same kinds of flowers we see growing in the grass in our own lawns. With iNaturalist, I’ve learned what these flowers are called, and which are the natives. It’s been helpful as I consider how to manage my “weeds.”

Walking in a drainage creek on Florida A&M campus. Note the red berries of the coral aridisa (Ardisia crenata) plant.

Into the “Wild Side” of FAMU’s Campus- a Forest of Invasives

Soon, we’re walking by a wooded area surrounding a ditch. That wooded area gets wider as we walk along the parking lot, and soon we’re heading in.

At first glance, this looks like a wild, forested ecosystem. We’re under a tree canopy with a lush green understory. Even the slabs of smashed concrete disappear as we travel further along the drainage creek, which gets wider and deeper as we trek on. Some exposed sandy spots have animal tracks, including what looks like a deer hoof print. It could be a spot in the Apalachicola National Forest. At first glance.

Lets look more closely at the individual plants. First, our eyes are drawn to splashes of red in the understory. These are the red berries of coral ardisia (Ardisia crenata), one of our more common invasive plants. Birds are attracted to the berries, which resemble those of our native holly trees. They’ll eat them, fly, and drop the seed somewhere else. When removing this plant, get it in a bag and keep the berries contained.

Green leaves carpet the ground. This is small leaf spiderwort, or wandering jew (Tradescantia fluminensis). Later in the year, it’ll produce little white flowers. It spreads easily, smothering seedlings and other low lying ground cover plants. Tradescantia fluminensis reproduces through vegetative cloning- every bit that breaks off becomes a new plant. If a stem section breaks off and falls into the creek, it’ll grow from where it lands downstream.

Even much of the tree cover is provided by camphor trees, which, as we learned last week, are Chinese imports.

We snap photos of these invasives, and others, like Japanese climbing fern and nandina, to upload to iNaturalist.

We Find Invasive Animals, too

Once we’re in the forest, Peter goes to town on logs and downed branches, uncovering a few frogs and lizards. As with the plants, he’s interested in finding and documenting invasives.

Peter finds a green anole (Anolis carolinensis), small lizards we often see in our backyards. In the not too distant past, they were the only anole species in North America. We now have a few other species of anole, which have been out-competing carolinensis and replacing it in a lot of its range.

He also finds two little frogs that are about the same size. At first, he thinks one of them is a Cuban tree frog, a Caribbean invader that has been in Florida for some time and is starting to make its way into our area. They will eat native frogs, lizards, insects, and spiders. Peter uploaded two photos to iNaturalist, where another user identified it as a native squirrel tree frog. Looking at the photo later, Peter agreed and changed his ID.

The next frog he found was an actual non-native, a greenhouse frog. Its page on the IFAS web site doesn’t list any known impacts. In other words, it’s not native, but not known to be especially destructive. And so here, we can draw a distinction between exotic invasive and other non native species.

We want our ecosystems to be made up of native species. After all, these plants and animals evolved together on this landscape, and formed ecosystems that best suited them here. When any new species gets added to the mix, it alters the balance between all of the other species in some way.

But some species are much more effective at spreading, or at displacing native species. These are species we want to track; especially, as in the case of the Cuban tree frog in Tallahassee, those that are just starting their invasion. This is where iNaturalist can be an effective tool.

Tracking Species in iNaturalist Projects

We spend roughly an hour making our way to Orange Avenue, where the creek opens up into kind of a ravine. We see a barred owl that flies off before we can photo it. And then there’s one of the more peculiar finds of the day, a grapefruit tree growing high above the creek. It’s a reminder that we’re on the campus of an agricultural school.

Now we’re done, and three teams have collected a lot of raw data. Kathryn typed up the results into a report she distributed to the bioblitzers. In one hour, these teams made 597 observations of 293 species of plants, animals, and fungi. She wrote a section on the high number of invasives in the forested area we visited, and noted as well that domestic cats threatened animal life on campus.

“Future surveys could be conducted systematically to inventory particular areas, classes of life, such as trees, or particular species of interest.” The report reads. Kathryn created a project within iNaturalist for FAMU’s campus, so that any observation, systematically made or not, will add to this inventory of species. Projects are how researchers can harness the power of all this raw data.

For instance, several locations have projects mapping invasive species. These can be as big as the Canadian province of Ontario or as small as a city park. This kind of project can help researcher track the spread of a species, or give land managers help plan removal or management of invasives. And while iNaturalist collects observations made by casual users, there’s no reason a researcher couldn’t coordinate volunteers to make a systematic survey of an area.

iNaturalist can also be used to map specific species or other taxa (genus, family, order, etc.) of species. many of the observations we make in Florida get added to an FWC project- Pollinators of Florida, Carnivorous Plants of Florida, and so on. Others have made more specifically focused projects (Do you know what an odonate is? There’s a project for them as well).

You can even create a project for your yard. I’ve been wrapped up in the planning of EcoCitizen Day and creating these videos and blog posts, so I haven’t done one for my yard yet. But, as evidenced by my year-long backyard bug project last year, I like knowing what I have in my yard. So I’ll end up doing this, and, inevitably, writing about it.

You can learn more about making and joining projects on the iNaturalist web site.

Next Week

After three weeks of urban Tallahassee adventures, we head into the Apalachicola National Forest. First, we explore a rare butterfly that needs fire to survive- the frosted elfin. And in two weeks, we return to the ephemeral wetlands of the Munson Sandhills as ordinary citizens get their feet wet in the service of science.

A young citizen scientist searches for amphibian larvae in an ephemeral wetland south of Tallahassee.

WFSU EcoCitizen is funded by Nature, a production of THIRTEEN PRODUCTIONS LLC for WNET and PBS. American Spring LIVE is a production of Berman Productions, Inc. and THIRTEEN PRODUCTIONS LLC for WNET.

Major support for Nature: American Spring LIVE was provided by the National Science Foundation and Anne Ray Foundation.

Additional financial support was provided by the Arnhold Family in memory of Henry and Clarisse Arnhold, Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III, the Kate W. Cassidy Foundation, the Lillian Goldman Charitable Trust, Kathy Chiao and Ken Hao, the Anderson Family Fund, the Filomen M. D’Agostino Foundation, Rosalind P. Walter, the Halmi Family in memory of Robert Halmi, Sr., Sandra Atlas Bass, Doris R. and Robert J. Thomas, Charles Rosenblum, by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by the nation’s public television stations.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1811511. Any

opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and

do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.