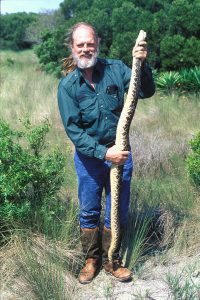

We’re in the Apalachicola National Forest with Dr. Bruce Means and the eastern diamondback rattlesnake. Bruce is considered a leading expert on this misunderstood species, and has written the definitive book on the rattler, called Diamonds in the Rough. Through its life Bruce has a lot to show us about the longleaf ecosystem.

Music in the segment was provided by Don Juan and the Sonic Rangers. You can see “Don Juan” Fortner with the Smooth Sailing Jazz duo, and with the Mary and Aaron Band.

Subscribe to receive more videos and articles about the natural wonders of our area.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Media

At one point in the video above, Bruce Means, his arm in a stump hole, begins to scream. Then, he turns to the camera and laughs. “I love to do that with groups,” he chuckles. He’s showing us a favorite hiding place of the eastern diamondback rattlesnake. Using a little bit of theater- and citing decades of research- he’s turning an unremarkable burnt out stump into a dynamic refuge within the longleaf pine forest.

This is Dr. Means’ style. He’s well known for appearing in National Geographic specials and also for two near death experiences at the fangs of his favorite rattlesnake. He is a showman and a personality, which can obscure that he is in fact a working scientist.

We’re at this stump hole in the Apalachicola National Forest because of what his research has told him. Forty years of studying the eastern diamondback have shown that the snake likes to stay warm here in the winter. Bruce shows us how soft the sapwood on the outside of the tree has become. He digs a hole and plunges his hand into the soft roots. Some small scorpions crawl out, but no snakes.

Bruce is hands on with the longleaf ecosystem. After we’re done filming the diamondback (the model for the cover of his new book), he wants to find a pine snake. He pulls the bark off of living pines, exposing more scorpions. He kicks a decaying log to see what might jump out. No luck, but I’m starting to see how much life lies out of sight in this habitat.

Bruce Means has studied the eastern diamondback for over forty years, and has worked in the longleaf ecosystem for over fifty. He is a former director of Tall Timbers Research Station and founder of the Coastal Plains Institute. He’s not a bad person to spend a day in the woods with.

Falling in Love with the Eastern Diamondback

Bruce first became interested in Crotalus adamanteus as a PhD candidate working at Tall Timbers. “When I was at the station, I kept seeing venomous snakes,” he recalls, “and the station workers would kill them.” It bothered him that a research station wouldn’t protect all living things, but it had been a tradition there. One snake in particular, the eastern diamondback, was not well documented. He became curious about this animal.

“I realized that this iconic animal of North America had never been studied,” Bruce says. “And I was in a really fabulous situation.”

After earning his PhD, he became a champion for the world’s largest rattler. “When I told the administration that I wanted to do a long term study, I killed two birds with one stone,” He says. He would better understand an understudied animal, and Tall Timbers would have to stop killing it.

The eastern diamondback isn’t federally endangered; however, its numbers have declined significantly. Its favored habitat is the longleaf pine ecosystem, which is down to three percent of its historic range. While this is a problem for all animals that depend on this ecosystem, the eastern diamondback is also regularly killed as a pest. And there are still many places that hold rattlesnake roundups, a tradition Bruce has fought.

By better getting to know the eastern diamondback and its habits, Bruce hopes to improve the reputation of an animal he calls the “Gentle Ben of rattlesnakes.” He started this in 1976, by feeding mice implanted with radio transmitters to rattlers. He has tracked and observed them for decades, and now he has released what he intend to be the definitive book about the eastern diamondback: Diamonds in the Rough.

“The Gentle Ben of rattlesnakes”

The biggest thing working against the eastern diamondback is human fear. It is the heaviest rattlesnake, and the most venomous. The sound of its rattling unsettles people. But the snake is not typically aggressive, and it only rattles in situations where it feels threatened. So while the stress of a video shoot gave us some great audio and movement, you’re not likely to encounter the animal this way in nature.

Bruce’s years of tracking the the eastern diamondback show that it spends a lot of time hiding in grasses, or under small shrubby oaks. When its tongue perceives that a rabbit or a cotton rat has been in the area, it will coil, and wait for days for its prey to pass back through. The diamond pattern of its scales camouflages it in the ground cover plants of the longleaf forest. It’s a predator well adapted to its habitat.

Unless we happen to startle it in its hiding place, it’s not an animal with much interest in us. We’re more likely than not to pass it by without noticing it.

And that raises an interesting question. Why does a hunter built for stealth have a big noisy rattle at the end of its tail?

Why do rattlesnakes rattle?

When Bruce Means considers the eastern diamondback, he does so in the context of millions of years of evolution. And not just millions of years of the snake’s evolution, but of its habitat as well.

“The reason there eastern diamondback prefers this environment” he says,” is because it is a long evolved and long lasting ecosystem type… An antecedent of it has been around- a grasslands, pine forest environment- since probably the late Miocene, which like 15-20 million years ago.”

The modern longleaf ecosystem evolved within the last million years. The rattlesnakes’ rattle helped it survive a forest that had once been full of large mammals.

Bruce motions to the snake. “During her ancestor’s evolutionary history, there were mastodons and mammoths and giant ground sloths and all kinds of large animals that were in her territory.” A diamondback had reason to fear the heavy footsteps of a mastodon. So, if one stepped near, it would rattle and bite it.

Even the eastern diamondback doesn’t have enough venom to take down so large a creature as a mammoth. But, it would be an unpleasant enough experience that the next time the mammoth heard a rattle, it would steer clear. Were you to visit an ancient longleaf forest, you’d likely hear more rattling than you would today.

Even the eastern diamondback doesn’t have enough venom to take down so large a creature as a mammoth. But, it would be an unpleasant enough experience that the next time the mammoth heard a rattle, it would steer clear. Were you to visit an ancient longleaf forest, you’d likely hear more rattling than you would today.

That’s because, about fifteen thousand years or so ago, a new animal arrived in its ecosystem and changed its rattling behavior.

For this “two legged monster,” as Bruce calls it, a thick rattlesnake is “a really good food item.” To the first Floridians, a rattling sound was a signal that food was nearby. And so, over thousands of years, diamondbacks learned to rattle only when directly threatened.

That’s why, on your next trip to the forest, you might walk by a few rattlers without even noticing them.

Diamondbacks in the Longleaf Forest

It’s impossible to learn about the eastern diamondback without gaining a good bit of knowledge about the longleaf/ wiregrass ecosystem. Every two or three years, fire sweeps through the habitat. Longleaf pine are fireproof, and ground cover plants in this system have evolved to survive and even thrive with regular burns. Herbaceous plants provide food and shelter to a wealth of animal species. These grasses and succulents feed the prey, and hide the predator.

One of the favorite hunting blinds of the eastern diamondback is wiregrass. Taking a few blades of wiregrass in his hand, Bruce points out its flowering seed heads and tells me that the forest was burned last May or June. “It takes a May or June fire to stimulate this species to flower the following autumn.” Without fire, wiregrass would never reproduce.

Another favorite hiding space are small, shrubby turkey oaks. These can grow to be trees, but fire restricts their growth. Bruce tells us that this plant is in the process of evolving to better adapt to fire.

Their presence in the longleaf habitat is a result of a few existing adaptations. One, it creates acorns within two years, meaning it can reproduce within a two year fire cycle.

Also, clumps of oaks are connected by a shared root system, like shoots of grass. While fire affects the above ground part of the turkey oak, the root system survives and sends up more shoots.

“It’s in the intermediate evolutionary stage of doing what the runner oaks have done.” Bruce says. Runner oaks never become full grown trees; they remain shrubs. In time, turkey oaks may do the same thing, better allowing them to become established in the longleaf forest.

Other animals and habitats in the Longleaf Ecosystem

Gopher tortoise burrows are a winter shelter for cold blooded rattlers, though, as Bruce points out, not their main winter shelter. They’re a critical space for over 300 animals in the longleaf forest, a place to hide from fire or cold. Last year, we went on a gopher tortoise EcoAdventure at Birdsong Nature Center. There, two biologists explored the burrows with specialized cameras (we do see a rattler hiding in a burrow).

One animal that relies on gopher tortoise burrows is the striped newt. They are born in ephemeral wetlands, and when those wetlands dry up, they move into the longleaf ecosystem. They’ve all but disappeared from the Apalachicola National Forest. However, last year, we tagged along with Bruce’s son Ryan, and Ryan’s family, as they worked to reestablish the striped newt population in the Munson Sandhills region of the forest.

Striped newts need shelter from fire, and they use gopher tortoise burrows as well as logs and stump holes like those favored by rattlers. A couple of years ago, we explored old an growth longleaf forest in Georgia in search of butterflies. As we learned, these logs and stumps alter the direction of fire in a way that protects butterfly larvae. Fallen trees may be the unsung heroes of the longleaf ecosystem.

A Forest Hundreds of Years Away From Being Complete

Lastly, you’ll see a couple of shots of red cockaded woodpeckers in the video above. I found those on a random trip to the Munson Sandhills, close to where we met Bruce. On our striped newt adventure, I encountered trees with artificial woodpecker cavities, and found that a crested flycatcher had taken one over. I returned to see if I could film woodpeckers.

Red cockaded woodpecker making a cavity in a longleaf pine. The sap running down the tree makes a slippery climb for predators.

Red cockaded woodpeckers build their cavities in longleaf pine that are at least 90 years old. Most of the longleaf that had covered the American southeast were clearcut, and much of the forest we see today is replanted. A lack of mature trees has left the red cockaded woodpecker endangered.

“These trees are approaching maybe 80 to 90 years of age,” Bruce estimates of the trees we saw in the Munson Sandhills. Biologists have been using artificial cavities to aid in the recovery of the red cockaded woodpecker as the forest ages. However, as I headed out to those artificial cavities one day, I encountered these woodpeckers making their own cavity in a tree.

It will take hundreds of years for the forest to return to something like what it had been. “Longleaf pine lives longer than any other pine in eastern North America, up to 500 years,” Bruce says. “So, for this stand to regain it’s original tree class composition, you gotta wait at least 500 years to get some really old ones!

“But still, even so, this is pretty good. This is a natural habitat as good as we can find it in our area.”

Getting to know the Means family

A busted kayak inadvertently led to our airing segments featuring brothers Ryan and Harley Means on consecutive weeks (long story). After seeing Harley’s segment a few week’s ago, one of my contacts at Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy pointed me towards Bruce and his new book, which Tall Timbers published. So, we’re hosting a family reunion of sorts on the WFSU Ecology Blog here in the early months of 2017.

Harley Means leads the RiverTRek team into Means Creek, in Torreya State Park. Means Creek was named for Dr. Bruce Means, Harley’s father.

Harley Means starred in our most recent RiverTrek adventure, exposing us to the ancient world of mega-sharks and dugongs along the Apalachicola River. Harley told us how, when he was a child, his father had taken him to the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines in search of salamanders and snakes. It instilled in him a love of nature, but, more importantly, the unusual geology of the area captured his curiosity. Harley Means is a geologist working for the Florida Geological Survey.

The older Means brother appreciated his somewhat unconventional upbringing; it is a big part of who he is today. As he was expressing this sentiment in our studio, I couldn’t help but think of Harley’s niece, Skyla.

Skyla Means’ parents, Ryan and Rebecca, signed her up for the adventure of a lifetime when she was ten months old. That’s when they started visiting the remotest spots in each of the 50 states. When we explored the Florida Big Bend remote spot with them, we got to see various photos of her hiking up stream beds, in canoes, or surrounded by mountains. She’s eight years old now, and has 17 state remote spots to go.

Ryan and Rebecca don’t know how she’ll grow to appreciate these adventures. Will they be as influential as Ryan and Harley’s childhood adventures with Bruce?

Anyhow, I didn’t set out to tell a family story. But, as I interviewed them all separately, I couldn’t help but make some small connections. It’s definitely an inspiration for me and the (admittedly more modest) outdoor adventures I have with my own sons.