In a steephead ravine, we enter a landscape as Appalachian as it is Floridian- perhaps a glimpse at the Apalachicola River of the ice ages. In part 3 of our salamander adventure, Bruce Means climbs down in search of the Apalachicola dusky, an animal he discovered here over 50 years ago.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

“We’re standing at one of the places I most love in this world,” Bruce Means tells the camera. “There’s a big surprise right behind me.”

Dr. Means stands in an open field, a row of oak trees a short distance away. When we get to the tree line, we look down. Up here, all we see are the tops of trees and a slope that descends into shadows. At the bottoms of those trees, however, lies the promise of rare plants and animals, a few of which aren’t found anywhere but the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines region. This is a steephead ravine.

We’re here in search of the Apalachicola dusky salamander. It’s a critter Dr. Means discovered as a graduate student at Florida State University in the 1960s and 70s. He was researching the southern dusky salamander, and exploring Florida wetlands to get a sense of all the places they’d be found. That search led him down steephead ravines, which had been largely ignored by biologists to that point. The dusky salamanders he found there were, at the time, classified as southern duskies.

It turned out to be a separate species, which he named in 1972- Desmognathus apalachicolae, the Apalachicola dusky salamander. In his quest to learn more about these salamanders, he found a habitat like no other.

Last year, we visited the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines region with Dr. Means’s geologist son, Harley. He led us down Means Creek- named for Bruce- in Torreya State Park. While in the creek, it didn’t feel like we were in Florida; it trickles down a rocky ravine as it runs to the Apalachicola river. The rocks and the fossils there have a lot to tell us about the ancient past of our area, a story Harley can read.

In a steephead, the plants and animals have a lot to tell us about north Florida’s ancient past as well. They’re here because of a geological phenomenon found almost entirely in north Florida (and on certain red planets). Before we get to know some of those species, let’s get a feel for this landscape.

Sliding into the Steephead

The slope is at about a forty-five degree angle, and covered with leaf litter. Rather than take a slow, careful approach to climbing in, Dr. Means slides down the loose leaves.

After a few slides, and careful steps where the slope is less severe, we come to a recently fallen hickory tree. Leaning against it, he says, “Sitting here, you don’t see the walls of the steephead collapsing, and the head of the steephead migrating into the landscape. But what you do see is the evidence of it, like leaning trees.”

It’s taken a few million years for the head of the ravine to get here from where it was born on the Apalachicola River, five miles away. Moving at about a mile or two every million years, this thing isn’t moving fast enough for us to see. But in the fifty years that Bruce Means has been coming to this particular ravine, he has seen large tree’s roots lose their grip on the receding wall, fall over and decompose completely.

So it’s moving slowly, but moving enough to affect living things within it. But what’s moving it?

Unlike most ravines, where rainfall shapes the surface, a steephead is the result of a very specific geologic process. We saw it last week along the Chipola River, searching for the Hillis’s dwarf salamander. It’s called seepage.

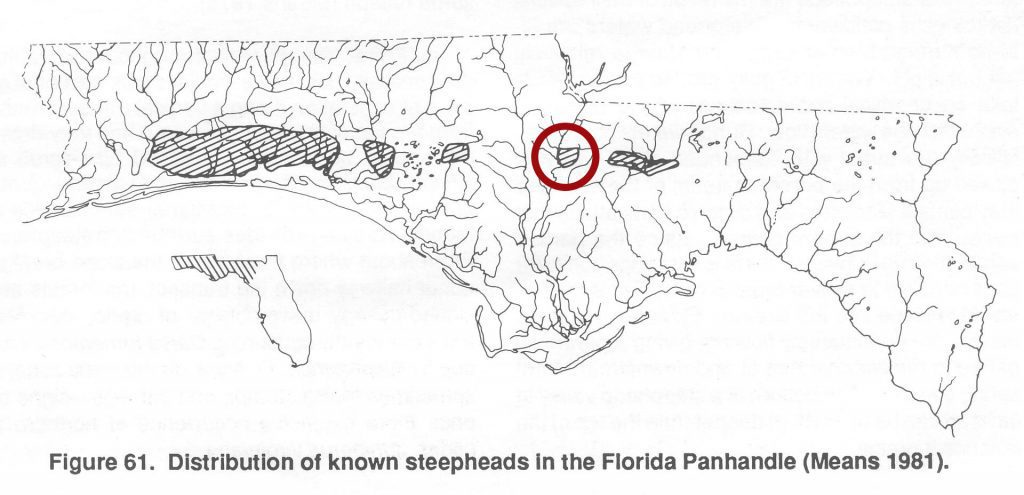

Image courtesy Bruce Means. I added a red circle to hilight the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines region.

Millions of Years in the Making

In the map above, you can see that steepheads occur in kind of a straight line across the panhandle. If you go back to our segment with Harley Means last year, he explained to us that the Bluffs and Ravines region had been under a shallow bay millions of years ago. Bruce Means thinks that steepheads occur where there would have been barrier islands. You might compare these to St. George and St. Vincent Islands, which enclose Apalachicola Bay about eighty miles below the red circle in the map above.

“If you go back millions of years, before the ravines that you see are in place, you would have had a relatively large, flat, sandy plateau,” says David Printiss. Printiss is The Nature Conservancy’s north Florida program manager, overseeing the Conservancy’s Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve.

Printiss is referencing a time after the coastline had expanded out into the Gulf of Mexico. The flat, sandy bottom of that ancient bay was now dry land. He describes rain hitting this ancient landscape, and collecting under the sand where it overlaid harder clay or limestone surfaces. These underwater lakes would expand, and when they finally reached river edges, they would begin to seep out.

“Now, when you’re at the actual Alum Bluff itself and you see [little waterfalls], those are the beginnings of small little steepheads.” Prinitiss says.

“Where the slope intercepts it, it leaks out, and carries with it sand grain at a time,” Says Bruce Means. “That little creek is carrying this material away with it downstream.”

One “sand grain at a time,” the steephead we’re in has moved five miles.

Steepheads are narrow and deep, and over millions of years, they’ve collected an interesting mix of plants and animals. Which brings us to the target of our search.

The Apalachicola Dusky Salamander

Bruce Means is tearing through leaves at the steephead amphitheater, where water bubbles out of the muck. He has no trouble finding a few Apalachicola dusky salamanders. One is a juvenile whose tail is growing back, and a larger female (as Dr. Means explains, the males have larger heads for fighting each other).

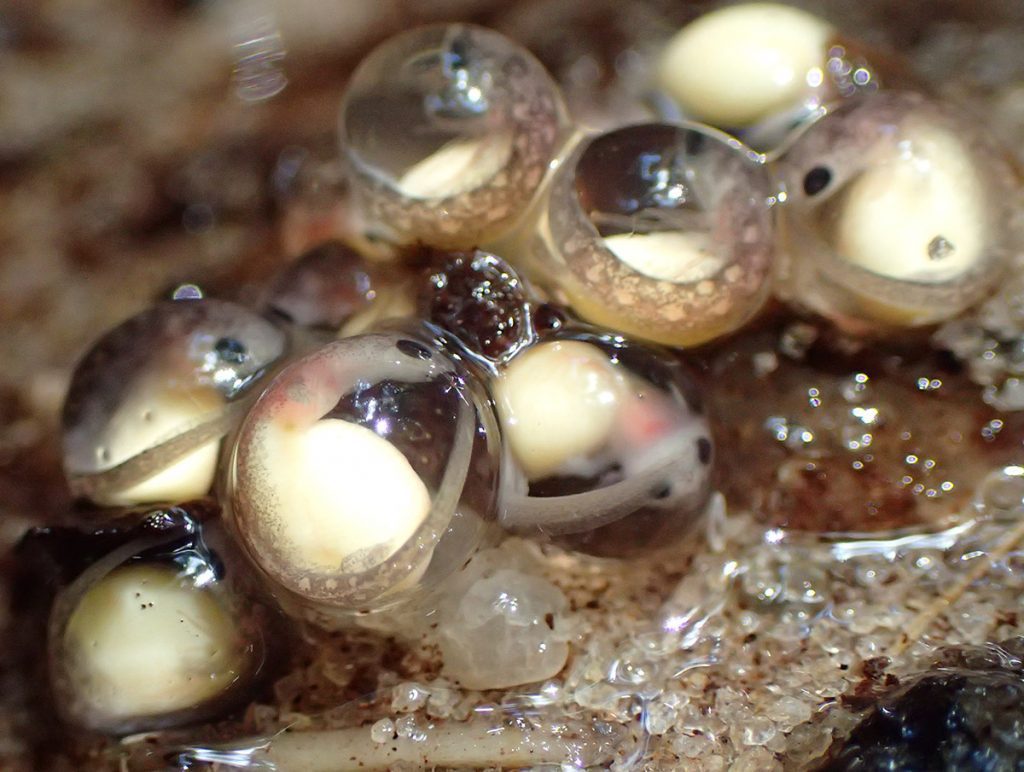

When Dr. Means turns over a log, we see the most interesting specimens. A mother scurries away from a cluster of eggs. The eggs are transparent, and using the macro lens on one of our cameras, we get a close look at the little babies.

A single Apalachicola dusky salamander egg, close up. You can see its eyes and limbs, and, even as translucent as it is, you can see its splotched pattern.

The seepage water is cool; like spring water it’s consistently in the upper 60s. It forms a little fast running, clear water creek: a much different environment than where we find the southern dusky salamander. Interestingly enough, even though the southern and Apalachicola duskies were once thought to be the same species, the Apalachicola is more closely related to species of dusky found in the Appalachian mountains than to the southern dusky.

That’s because, like many of the species in the Bluffs and Ravines region, its origins lie northward. These plant and animal species are, climatologically speaking, snowbirds that never left sunny Florida.

Steepheads and the Plants and Animals that got Left Behind

A couple of weeks ago, we visited archeological sites dating to the end of the ice ages. We saw early Floridians adapting to a landscape that was physically changing, and one that saw a change in plant and animal communities. The Pleistocene era was full of these changes- warming and cooling, and sea level rising and falling.

Life on earth was continually adjusting to these changes.

“During the last glaciation,” says David Printiss,” all species from the Appalachians were pushed southwards by the cold weather.” These changes occurred over thousands of years, so everything from large tree species to little salamanders would shift their ranges as temperatures changed.

When these Appalachian species found steep, narrow ravines with cool, flowing water, it felt like home. So when temperatures got warmer again, many northern plants and animals left behind small populations in ravines and slope forests. Some entire species remained here, and only here. And so we have an interesting mix of flora and fauna that makes steepheads unique.

“We have the southern end of the distribution of species like mountain laurel that you wouldn’t expect.” says David Printiss. “And you have other species that you’d call glacial relics. They were left behind, so their sister species are up in the Appalachians.”

One of these is the Apalachicola dusky. Another is a tree species that’s clinging to life in the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines.

The Torreya Tree (Torreya taxifolia)

“There are other [relic] species like the torreya tree that… just simply could not run uphill fast enough and was left behind.” says Printiss. “So its global distribution is Torreya State Park and the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve.”

It’s a small population, entirely confined to a small area. When torreya trees started contracting lethal fungal pathogens, it almost wiped out the entire species. These trees had once grown as tall as sixty feet, but plants in this wild population haven’t been able to mature past their juvenile stage (the plants has been successfully cultivated elsewhere).

There’s another similar evergreen that’s endemic to the Bluffs and Ravines region- the Florida yew (Taxus floridana). Consulting my Florida natural Areas Inventory field guide (the 2000 edition FNAI was recently giving away), I read that while the two trees look similar, the torreya has stiff, sharp needles while the yew’s needles are soft to the touch.

Pyramid Magnolia (Magnolia pyramidata)

Here we have a rare species at the southern edge of its range. Dr. Means spotted the tree above while we were hiking out of the ravine. It blooms from about March to June, so we would have just missed seeing its large white flowers in July.

Above is a pyramid magnolia sprout we found hiking the Garden of Eden Trail at the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve, in 2013.

Florida Star Anise (Illicium floridanum)

This is a plant that grows in ravines and slope forests. In the photo above you can see that it blankets the edge of the ravine stream. It’s one of two plants in the Illicium genus in Florida, the rest of the 40 Illicium species are Asian natives. While the Asian varieties are used as spices (like star anise), Florida star anise is toxic.

“It is one of the oldest angiosperms, meaning flowering plants, in the world,” says Dr. Means, referring to the Illicium genus.

This is another spring bloomer, so we missed its large, red flowers. The plant is also known as stinkbush. As Dr. Means explains, “It stinks! Like rotting beef! And that’s how flowers first got started, we think, in the evolution of flowering plants.” The smell would have attracted flies as pollinators, much as a rotting carcass still attracts flies today.

We could have spent much more time looking for rare steephead plants, a mission for another day. Having concluded our salamander mission, we climb out. And this is where we find one of the rarest plants we’ve seen today. And it was right on the side of the road.

Apalachicola Rosemary (Conradina glabra)

As we’re loading up the van, Bruce Means gets excited about what he sees on the shoulder of the road. Here is a flower that only exists in Liberty County, Florida. The FNAI Rare Plant guide states that Apalachicola rosemary grows in the upper edges of steepheads, where they transition to upland sandhill pine forests. And also, they like roadsides.

Visiting Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines

Today’s adventure, and last year’s Means Creek hike, took place in Torreya State Park. However, these are parts of the park not open to the public, and which we visited with special permission. You won’t see any steepheads in the part of the park that’s open to the public; those ravines are the more common gully ravine.

Of course, there are still many rare plants and ice age relics, and if you visit the Gregory House, you can see some planted torreya trees. While you’re there, you might enjoy one of my favorite high up views of the Apalachicola River:

Along the Apalachicola, the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve‘s Garden of Eden Trail lets you hike into steephead ravines. Like many of the Torreya trails, the trail has more changes in elevation than most Florida trails, and can be challenging. When Doug Alderson led a multi-day hiking trip here in 2014, at least one hiker described these trails as almost Appalachian.

You can’t camp at the Bluffs and Ravines Preserve, but, like Doug and co., you could camp nearby at Torreya and hike both sets of trails.

When you get to the end of the Garden of Eden Trail, you’ll see one of my favorite all time sights:

The Apalachicola River as seen from atop Alum Bluff. Alum Bluff is Florida’s largest geological outcropping- this is the highest natural point above a Florida River. At the river bend on the left, if the water level is right, is the sand bar where RiverTrekkers camp on the first night of their adventure.

Visiting other Steephead Ravines

Outside of the Apalachicola area, you can visit some smaller steepheads at Lake Talquin State Park. The largest steephead ravines are on Eglin Air Force Base in the western panhandle. The Florida National Scenic Trail sections here run up and down ravines. Hikers need a permit before entering section, and there may be a fee (follow the link for more information on fees).

Just for kicks…

This summer, my family and I happened to spend some time in the Smokey Mountains in North Carolina. The Smokey’s are a subrange of the Appalachian Mountains, so we saw the kinds of environments that would have migrated south during the ice ages.

One day, I took a hike in the Joyce Kilmer/ Slickrock Wilderness Area in the Nantahalla National Forest. The trail I hiked just happen to have plenty of rocky stream beds. So, for the sake of visual comparison, I thought I’d share some photos of that environment:

The trails in this Wilderness Area offer different challnges than the Florida Trail in our Bradwell Bay Wilderness. At times, like here, the trail devolves into a pile of rocks or slippery water crossings. Also, fallen trees aren’t immediately removed from mountainside trails.

The biggest challenge for me was fording Slickrock Creek. Had I followed the full trail, I would have had to cross it nine times to stay on the trail. As the name implies, the rocks on the creek bed are slick, and rains earlier in the week had the water flowing a little fast.

When I saw the thickness of the sphagnum moss on the wall, so soon after shooting these segments, I immediately thought of Bruce Means tearing apart sphagnum in search of salamanders.