Last week, we met Morgan Smith’s team and got to know their archeological sites on the Silver River. Today, we’ll revisit their Wacissa River site, see some of the artifacts and fossils they’ve found, and learn what they can tell us about ice age Florida. We’ll also look ahead to potential off shore digs.

Special thanks to Shawn Joy, Morgan Smith, and Matt Vinzant of Karst Underwater Research for letting us use their underwater footage. Morgan’s research is sponsored by the Felburn Foundation, Center for the Study of the First Americans, Texas A&M University, and the PaleoWest Foundation. He would like to thank the Silver River State Park, Florida Bureau of Archaeological Research, and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

Subscribe to receive more videos and articles about the natural wonders of our area.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

In the video above, we visit three archeological sites on two rivers. When you watch footage from each site, one sticks out as the most visually striking. It’s an underwater cavern at the head spring of the Silver River, and it’s full of mammoth bones. It looks like a cool place to explore. But it’s also the site with the least scientific value.

The footage from the other two sites looks similar. Divers methodically work the edge of flat walls of dirt, plucking and bagging small bits from them. FSU Anthropology master student Shawn Joy makes notes on a clipboard while a large tube vacuums up loose sediment. The process is less dramatic, though the resulting story might not be. And telling that story is Morgan Smith’s job.

Morgan Smith enters a cavern at the headspring of the Silver River. Image Courtesy Matt Vinzant, Karst Underwater Research.

Morgan is a Ph.D. student at Texas A&M University’s Center for the Study of the First Americans. He and his team are trying to find the story locked within the banks of the Silver and Wacissa Rivers. It’s a tale of a people long gone, 10,000 years or more. They lived in a Florida much different than ours; these sites can teach us about that landscape as much as they can about the people who lived in it.

So why does the site with more and bigger bones have less to tell us?

Grading Morgan’s Sites- What Can They Tell Us?

“We need three things in the archeological community to present [a site] as a true site,” Morgan Says. “We need unequivocal artifacts. We need absolute radiocarbon ages. And we need secure geologic context.”

Let’s grade Morgan’s sites against these criteria.

Large bones, likely mammoth, among rocks in the head spring of the Silver River. Image courtesy Matt Vinzant, Karst Underwater Research.

1. Mammoth Spring, Silver River

This is the cool-looking site I mention above. The head spring of the Silver River contains several Columbian mammoths and maybe mastodon bones. These were found close to several Paleo-Indian projectile points. So the site has unequivocal artifacts. You need organic material to obtain radiocarbon dates, and the bones may contain collagen to sample.

The problem with the site is the third point- geologic context. In the video, you can see bones lying on the floor of the cavern. Have they always been there, or did they fall in later? You can ask the same question about the points found here in the 1960s.

All Morgan can say for certain is that Paleo-Indian people and mammoths were in the area. But did they interact? Were they even here at the same time? They might have been, but without context, Morgan can’t say so definitively.

Morgan shows his Guest Mammoth site findings to Daniel Morgan, Assistant Park Manager at Silver Springs State Park. To the left is a bone from either a mammoth or a mastodon, and on the right a Columbian mammoth tooth.

2. Guest Mammoth, Silver River

Downriver aways, Morgan and friends are re-excavating a site discovered in 1973. Charles Hoffman’s original dig turned up projectile points, and mammoth bones that appear to have been butchered. So far, Morgan has found a bone from either a mastodon or a mammoth, a mammoth tooth, and several pressure flakes. Pressure flakes are the small shards that fly off of a stone as it gets knapped into the shape of a tool or point. The angle at which one rock hits another gives the flakes a distinct shape, which is how archeologists would distinguish them from small rocks.

So Morgan doesn’t have a wealth of artifacts from his re-excavation (he will return next year). He was able to extract bone collagen from the mammoth bones, though, so he will get a radiocarbon date for the site. Both Morgan and Hoffman found artifacts in the dirt with the mammoths. But is that everything we need to establish context?

“The question is whether or not temporally they’re associated,” Morgan says, ” whether or not people interacted with these mammoths, or whether or not these artifacts and the mammoth bones came to be associated by geological processes or rivering processes.

In other words- they’re in the dirt together, but did the movement of the river or its sediments put them together? We’ll look at how Morgan tests for that in a second.

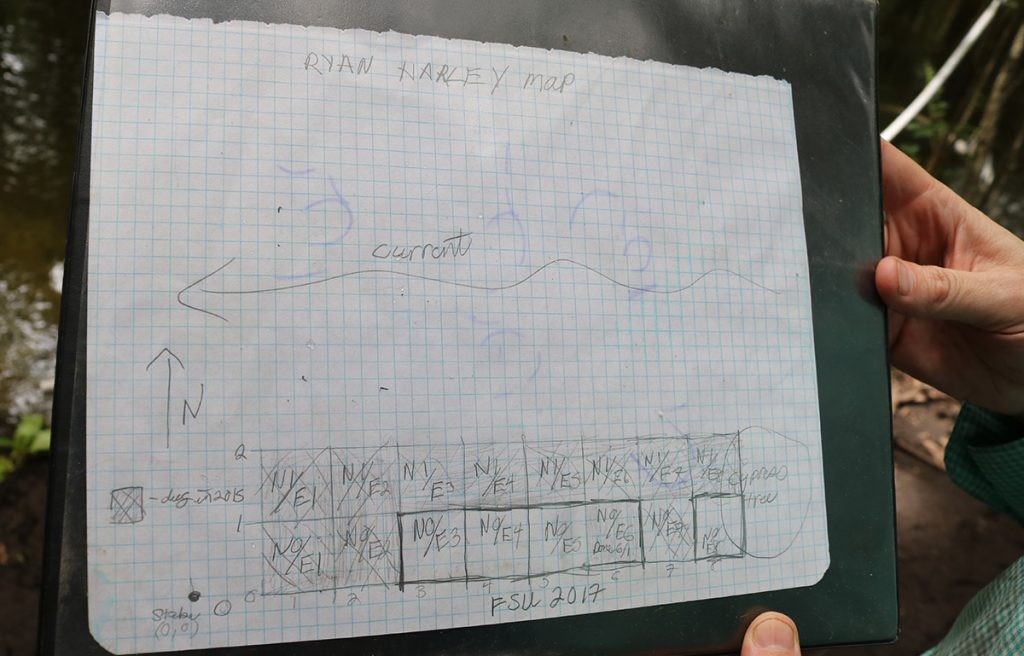

Dr. Jesse Halligan shows the research team’s map of the Ryan-Harley site. The four sections in the center of the bottom row were being excavated by Dr. Halligan’s students at Florida State University.

3. Ryan-Harley, Wacissa River

One day, Ryan and Harley Means found Suwannee style points on the bottom of the Wacissa River- out of context. However, these were eroding out of a riverbank nearby. Dr. Jim Dunbar, the state archeologist at the time, excavated the site in the late 1990s, and found a sediment layer full of Suwannee artifacts. Based on radiocarbon dating, Suwannee-style projectile points date to about 10,000 years before present. They’re indicative of a culture that inhabited north central Florida around that time.

In Morgan’s recent digs, they’ve found several more artifacts and bones. Some of the bones belong to animals that went extinct at the end of the last ice age. Everything is in context.

We’ll look at some of what Morgan has found there in a second. It’s enough to start telling the story of the Suwannee people, and the Florida of the late Pleistocene.

Testing for Context

First, let’s go back to Guest Mammoth for a second. Morgan has found artifacts and bones in the ground together but still doesn’t know if it’s secure geologic context. How does he figure this out?

Dr. Jim Dunbar’s crew (Jim’s at the right of the boat) prepares to take a core sample of the Ryan-Harley site in 1999. Photo courtesy Florida Geological Survey

Sediment Core samples.

Morgan explains: “It’s basically a three-inch diameter aluminum pipe that we drive into the ground as deeply as we can. And then we split it open, and it provides us with a nice little snapshot of exactly what the sediment looks like.”

In other words, it’s not just about whether the bones and artifacts are next to each other in the ground. The question is, are they in the same sediment layer? The river has been depositing layer after layer of sediment over the millennia, and different layers will have different compositions and organic material that can be dated.

Excavating a straight wall

“As we’re excavating, we maintain straight walls as much as we can, so that we can clean off a really nice profile of the sediment layers,” Morgan says. In addition to keeping the wall straight, they excavate in five-centimeter increments and take soil samples of each layer. They keep that wall as neat as possible, and they map everything they take out. In this way, they know precisely in what sediment layers they found each item.

Building the Suwannee Toolkit | Artifacts from Ryan-Harley

The artifacts that drew Ryan and Harley Means to this site originally are also the showiest. These projectile points identified the people at this site as Suwannee.

Suwannee projectile point found at the Ryan-Harley site, lower Wacissa River. Image courtesy Morgan Smith.

Since this is one of the few sites with Suwannee material in context, Morgan and crew can start to figure out a few things about these people. The pressing question is- when were they active in Florida? Accurate radiocarbon dates will tell us definitively. But there’s so much more to learn about these people and their environment. And to tell that part of the story, Morgan has a wealth of other items to help him.

“Projectile points are nice and they’re diagnostic,” Morgan says, “but it’s really the tool forms and the flakes and the other materials… that tell the best story.”

This small hand ax is called an adze. If you take a close look at the edges of this and the points above, you can see grooves where it was knapped. Imagine the small bits of rock that flew off as a Suwannee person struck it with another rock. They would have a similar shape to those grooves, which is how archeologists recognize them as pressure flakes.

Imagine now a Suwannee hunter returning with a catch- perhaps the turtle whose shell we’ll see in a second, with possible cut marks on it. The hunter wouldn’t want to dull his adze cleaning the meat off of the bone, so he’d need another specialized tool for the job. The shape of this tool lets archeologists know this is a bone scraper.

Animals of Ryan-Harley | Imagining the Pleistocene Wacissa

Now we have a general sense of Suwannee technology. But what did it look like where they lived? When you kayak the Wacissa River, it’s plenty wild and full of wildlife. It’s completely surrounded by protected land, so you don’t see houses or any other man-made structures. Instead, you see thick floodplain forest.

But Suwannee people were around when temperatures were cooler, and the sea level lower. So there were likely to be differences.

Since riverbanks do a good job of preserving organic material, Morgan has found seeds and other plant matter. And there are also plenty of bones. Knowing what we know about animals and their habitats, we can start to imagine the landscape.

One clue that this was still an aquatic environment is this bit of turtle shell. Note the three lines, evidence that the animal had been butchered by humans.

Morgan’s crew also found muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus). These large rodents are adapted for life in wetlands. They can tightly seal their mouths behind their large incisors (above right), allowing them to gnaw while underwater.

This bone belongs to another species common in the area today- white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). Morgan believes this deer mandible may have a small cut mark on it. We know from their projectile points that the Suwannee people were hunters, and would have gone after large game like deer. But, as Morgan told us in 2015, the presence of smaller animals with marks means that the Suwannee people also trapped smaller animals for food. To Morgan, this is a clue that the Ryan-Harley site was more than a temporary campsite.

Extinct Ice Age Animals | Dating Ryan-Harley

Morgan and friends have also found alligator and fish bones in the Suwannee layer. From what we’ve seen so far, the Wacissa coming out of the last ice age doesn’t look too different from today. This picture changes when we look at some of the other fossils Morgan has found.

Teeth belonging to Tapirus veronensis, an extinct species of tapir that had been common to the American southeast. Image courtesy Morgan Smith.

Tapirus veronensis was a species that went extinct around 11,000 years ago. Tapirs are pig-shaped animals with a short trunk like that of an elephant; modern tapir species are found in South America and Asia.

These bones belong to Palaeolama mirifica, a name that means “early llama.” Image courtesy Morgan Smith.

The bones above are from another species that went extinct at the end of the ice age- Palaeolama mirifica, or “early llama.” They’ve also found horse bones at the site, and the presence of these two species paints another picture of the area around the site. These are grazing animals that would favor a grassier location.

“This indicates that the area would have been a bit more open during the site’s occupation than today,” Morgan says.

Last week, Morgan described what the Silver River might have looked like at the time. The Silver River’s springs would have fed a series of ponds. Mammoths are also grazers (whereas mastodons ate leaves from trees), and so their presence indicates grasslands there as well.

The Multidisciplinary Underwater Archeologist

As I interview Morgan and his colleagues, I start to notice how many different scientific disciplines they draw upon for their work. They identify artifacts (archeology) and bone fragments (biology) lying in different sediments (geology).

“We not only have to be familiar with archeological methods and theory,” says Adam Burke- like Morgan, Adam is a Ph.D. student at Texas A&M, “but also paleontology, geology… geomorphology is important- so, understanding the ways in which landforms are created and changed…. botany…”

And for the work they do, they have to know how to dive, and to excavate while diving.

Adam’s doctoral research focus compliments Morgan’s. It’s a little too specific to fit into the six-minute story we tell in the video, but it could give us some important information about the Paleo-Indians in Florida.

Where did this chert come from?

This artifact is either an adze or a bone scraper, Morgan was unable to tell. Like the tools above, it was crafted from chert. Note the variations in color between the different artifacts found at Ryan-Harley.

Adam is looking at two things. One is the geochemical analysis of chert. Chert is a type of rock often used by Paleo-Indians to make tools and points. Adam’s other focus is the taphonomy of stone tools, “So, what happens after they’re put in the archeological record.” That is, what happened once it was left behind and buried in sediment?

Chert underwent certain chemical changes when Paleo-Indians quarried it and made tools from it. It may also have undergone changes, depending on its environment, once sediment covered it and it sat for thousands of years.

“So, in these submerged contexts especially, many of the artifacts that you find littering the river bottom end up being stained or discolored.” The color is affected by geochemical processes, and if he can figure out what chemicals were changing the color, he’ll better know the original chemical composition of the chert. Knowing that he can figure out where it came from.

Knowing where the chert came from, and where it ended up, helps archeologists know how Paleo-Indians were moving. For instance, did Suwannee people cover a lot of ground in their lives? Did they stay closer to a central location? Answering these questions would give Adam and Morgan greater insight into Suwannee culture.

So how does Adam determine the geochemical changes that have occurred in chert? He uses Neuron Activation Analysis and Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry. That’s how.

Following the Paleo-Aucilla Out To Sea

The Wacissa River joins with the Aucilla, another Florida river with major archeological sites. The Aucilla River ends where it drains into Apalachee Bay in the Saint Marks National Wildlife Refuge. But in another sense, it doesn’t.

There’s the Aucilla River we know today, and then there’s the Paleo-Aucilla. The latter is the river that, when sea level was lower, continued onto what is now the continental shelf. Each of our rivers has a paleo channel that was, as Dr. Michael Faught puts it, “drowned, or inundated, by sea level rise.”

When the Suwannee people were active, this extended landscape was part of their range, and Suwannee points have been found far offshore. People have always been found by water, and so they were likely to have been along these paleochannels. Dr. Faught and Shawn Joy are looking here for more sites.

The challenge is to find these channels out in the Gulf.

“The current state underwater archeologist, Ryan Duggins, did his PhD on that,” Dr. Faught says. “And he did modeling on where the channels would be. He also in that modeling came up with places where there might be springs coming up.”

If he and Shawn get a grant they recently submitted, they will use this model to guide their search for sites.

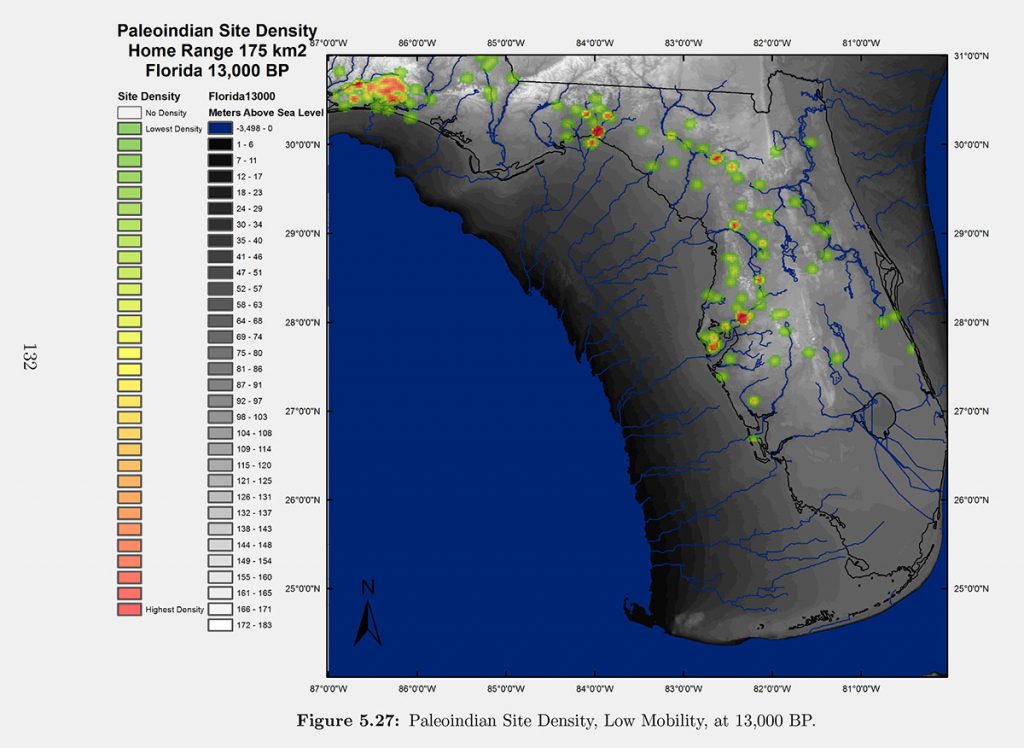

The figure above, from Dr. Duggins’ dissertation (link to PDF), shows his projections of where rivers ran 13,000 years before present, based on the topography of the Gulf floor. The colored spots show where Paleo-Indian sites have been found on land. In his dissertation, he calculated the distances of these sites to current river channels and springs, and, based on that, determined where sites might be in relation to paleo-channels in the Gulf.

Right now this is just a model. If Shawn Joy and Michael Faught are successful in their grant application, they can put this model to the test.

The Role of Avocational Archeologists in Finding Sites

While at the Ryan-Harley site, we were visited by Ryan and Harley themselves. The Means brothers were diving the river about twenty years ago or so, when Ryan spotted a Suwannee projectile point lying on the river bottom. Harley quickly found another one, and they reported the site to Dr. Jim Dunbar, who was state archeologist at the time. Dr. Dunbar performed the first excavation of the site, which Morgan is now revisiting.

Ryan and Harley reported the points as part of the Isolated Finds Program, which has long been shut down. There is currently no mechanism for amateur archeologists- avocationals- to search for and report sites to the state. Dr. Dunbar told us why he thought the program didn’t work, and how it shielded looters who would sell artifacts on the black market. Ryan and Harley feel differently, and that citizens should be involved in this process.

Before we ended our interview at Silver Springs State Park, Morgan wanted to share his views on the matter.

“As far as I’m aware, there’s not a single underwater archeological site in Florida, with the exception of a couple of sites offshore, that was found by a professional archeologist,” Morgan says. This includes all of the sites Morgan’s team is excavating in this video. “Us professional archeologists haven’t done a great job of fostering a relationship between professionals and collectors. And that’s something I’d like to see remedied in the future.”

He admits that Isolated Finds “didn’t work particularly well.” However, “We were getting more useful data during the program than now… I would like to see a responsible, well-organized program that involves active people that are really interested in this kind of stuff.”

One reason he’d like to see this is practical. “It’s difficult for the ten submerged prehistoric archeologists in Florida to survey all of this area… we need more boots on the ground.”

The other reason this interests him is his is that he wants the public to be engaged in archeological research. During his three weeks excavating Silver Springs, he gave three public talks about his research there.

“When we don’t involve the public, we lose the trust of the public, and we lose interested parties who provide funding for a lot of archeological research, who volunteer on archeological projects, and things like that.”