As I write this, frogs from the Caribbean are colonizing Florida. The two most common are the Cuban tree frog and the greenhouse frog; each has become widespread and each takes resources from native frogs and other insectivores. Try as we might to eradicate them, they are numerous and small. Unfortunately, like many invasive species, they may well become a permanent part of our ecosystems.

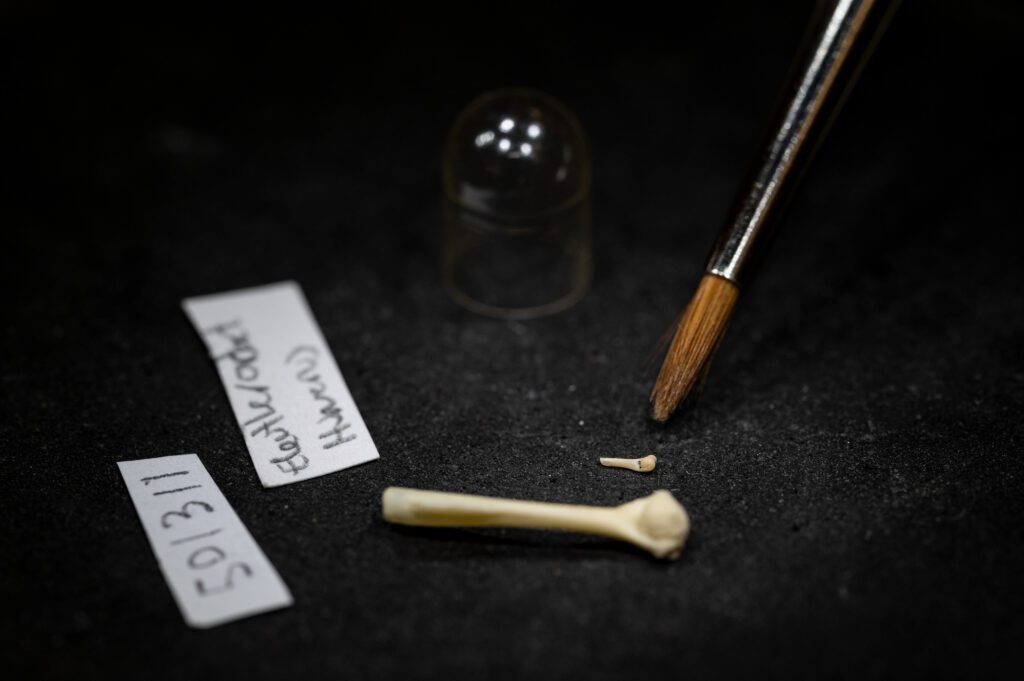

According to newly published research, this isn’t the first time Florida has been invaded by Caribbean frogs. One of Florida’s first frogs, in fact, migrated from the Greater Antilles some tens of millions of years ago. The frog is in the genus Eleutherodactylus, possibly an ancestor of the greenhouse frog (Eleutherodactylus planirostris).

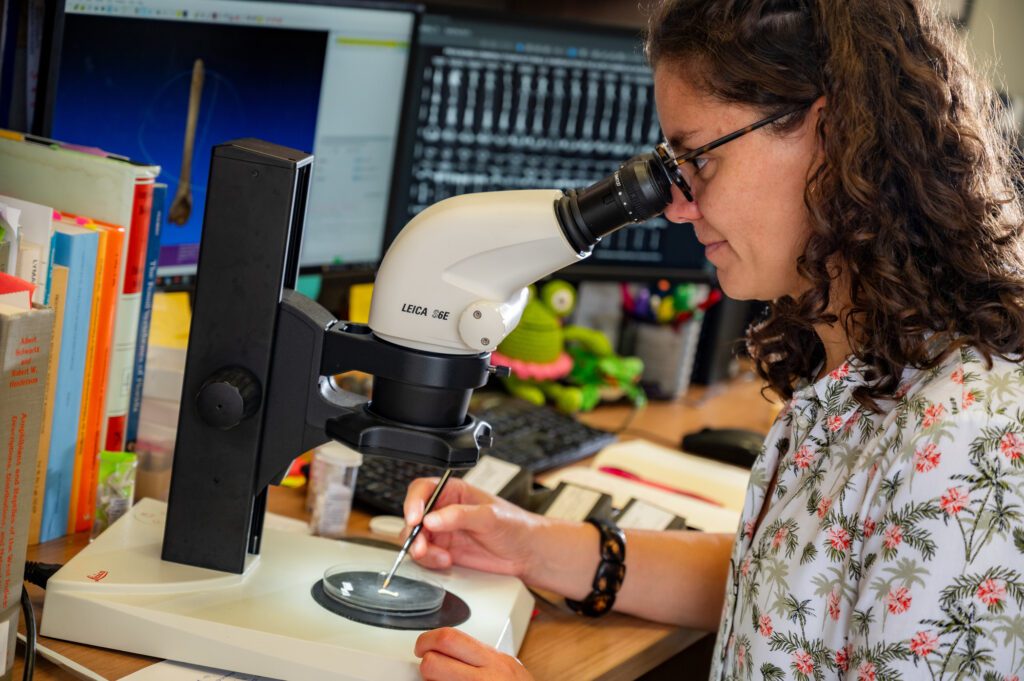

Maria Vallejo-Pareja, a PhD student at the University of Florida, made the discovery while looking at fossils collected from the 1970s through the 1990s. The fossils are part of an extensive collection at the Florida Museum of Natural History at UF. As a biologist with a focus on paleontology, the collection is a dream.

“The collection here is amazing because it does have, of course, the largest diversity, the largest collection of Florida vertebrates,” Maria says. “That is really good because Florida has terrestrial vertebrates from the Oligocene (33-23 million years ago) to Pleistocene (2.5 million-11,700 ya). So you can have actually a continuum of time, a fossil record that you can track in time where things are coming from.”

In piecing together the story of this ancient frog, we can learn a lot about Florida’s early years above sea level.

Florida before Frogs: a geologic history

It’s hard to imagine Florida without frogs. This is a land of waterways, from rivers to lakes to small ponds and wetlands of every description. The first frogs evolved on Earth about 250 million years ago, and yet frogs in Florida don’t appear in the fossil record until about 30 million years ago. The oldest fossil belongs to a burrowing toad described in 2019 by Maria and the Museum’s herpetology curator, Dr. David Blackburn. Maria’s Eleutherodactylus fossils date between 26-28 million years ago.

So, why no frogs before that? Because there was no land in Florida.

You can see some of Florida’s geological history on a satellite map. Notice how the peninsula sits on a wide area of shallow water? This is the Florida Platform, and for over 100 million years, all of it was a shallow sea. It’s like the map above, but with no peninsula. Then, about thirty million years ago, South America and Antarctica separated for the last time. A new ocean current circulated water by Antarctica, spreading cold water across the earth and spurring the creation of large ice sheets. Sea level fell, and Florida emerged. Rivers brought sediments down from Georgia and built higher ground that, on and off, has stayed above sea level.

Now that Florida was above water, land animals could move in. It took millions of years for Florida to completely rise above sea level, and her frog fossils date to a period where the process was ongoing.

Exploring a collection of fossils – and data

The fossils Maria examined in her research had been collected long before she arrived in Gainesville. I have an image in my head of her entering a warehouse like the one at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark, dusting off box after box to look for long-forgotten frog bones. The reality is a little less dusty and a little more digital.

“It’s well organized and well documented,” she says. “When you have fossils, you want to have as much information from where it comes, who collected it, when they collected it, what was associated with it.”

All of this information is gathered into a searchable database, along with 3D scans of bones. This allows her to look at the structure of bones without always having to handle them. She also has access to scans of bones from around the world.

Based on the rock or sediment layer in which the fossils were found, Maria has a general age for the fossils she’s examining. She has bones from cities in different parts of the state, from Brooksville in central Florida to Live Oak in the north. Starting with this information, she compared the bones to the bones of other frogs in Florida’s fossil record.

As she sorted through scans of these fossils, though, she didn’t find any that were related to hers. Eleutherodactylus was in Florida long enough to establish itself over a range of at least 125 miles – the distance between Brooksville and Live Oak. But it didn’t match with any of Florida’s living native frogs.

“You can find them in Texas and or parts of the Gulf Coast, but they’re not native to Florida. So when we started finding that these frogs didn’t match the characteristics from other families that were here in Florida, we kind of expanded our search and said, okay, so if they’re not toads or not bullfrogs or they’re not tree frogs or narrow mouth toads, let’s see what else they can be.”

This led her to the Caribbean. There, she found an answer to one question, and yet also a few more questions that needed answers. How did they get here? And where did they go?

How does a frog get from the Caribbean to Florida?

How does any animal make its way off an island? Swimming or flying, typically. But frogs don’t fly, and they don’t swim long distances through salt water.

Might sea level have dropped low enough in the early Oligocene to make a land connection between the Greater Antilles and Florida?

“There was no land connection that we know of between the Caribbean islands, or the Greater Antilles, at that time with Florida,” Maria says. “What has been proposed is that there was a big current of water circulation going north right between the Greater Antilles and the peninsula offshore.”

This brings us back to water. But surely the frogs didn’t swim.

For a possible answer, Maria looked not at geology, but at the biology of the frog’s living relatives.

Direct Development in Frogs

Maria’s fossils belong to a frog in the family Eleutherodactylidae, also known as rain frogs. The family has 200 species spread across the Caribbean, Central America, and part of the U.S. Gulf coast. Rain frogs reproduce differently than most frogs, and that may offer an important clue as to how Eleutherodactylus arrived in Florida.

“They’re really good at dispersal because this specific group of frogs has something that is called direct development,” Maria says. Most frogs lay eggs in water. The eggs hatch and frogs metamorphose through different stages of tadpole and polliwog development, ultimately becoming adults. Not so with rain frogs.

“With this group of frogs that are direct developers, everything happens within the egg,” Maria says. Rain frogs hatch from the egg with all four legs and a short tail, which they soon lose. Eleutherodactylidae also have eggs with thick shells, which don’t need to sit directly in water. “They don’t have that constraint of needing a pool of water like a river or lake or a creek or a puddle. They can actually be transported in a mass of vegetation or something like that.”

That’s one hypothesis, and one Maria would have difficulty testing. For her, it’s part of the fun of studying an animal that has long since vanished from the earth.

“I think it’s very exciting because we are exposed to things that we didn’t know… and now we don’t have the answers immediately,” Maria says. While she really wants to know, it also “opens like a door for more research to keep asking questions about, okay, so are there any other places where we can find more fossil frogs? Are these frogs maybe already collected and haven’t been identified in our museum, [from] the Gulf Coast, for example?”

Appreciating the small, slimy things

Maria has always had an interest in “herps,” those creepy-crawly reptiles and amphibians. She wrote her master’s thesis on snakes and is now focused on frogs. When it comes to fossils, megafauna such as mastodons and megalodons get a lot of attention. But those animals shared the landscape (or seascape) with many more smaller animals. Frog bones are harder to find than those of mastodons, but both animals were part of an interconnected web. Every discovery about a small animal helps us understand the world of those bigger animals, and of the ecosystems that evolved into those we have today.

Animals in Ancient Florida

- Alum Bluff: On Florida’s largest geological outcropping, we find over 20 million years of fossils, including the largest shark to ever exist: the Megalodon.

- Cave Crustaceans: Research into cave-dwelling amphipods offers clues as to how connections between Florida’s underground caves have changed over geological time.

- Underwater Archeology: When humans first arrived in Florida, they encountered a landscape radically different than what we see today, filled with animals that have long gone extinct. Archeologists are uncovering glimpses of this woirld buried in FLorida waterways.