At 8:30 in the morning, I walk into the Tallahassee Museum, humidity clinging to my t-shirt, the thermostat already rising. A half-hour before the museum opens, I gather with my team from WFSU, Suzie Buzzo, an animal curator at the museum, and Chris Bruton, Lead Keeper, to watch them ready the Florida panthers for the day.

Walking past industrial refrigerators filled with food in what Suzie referred to as “the kitchen” we come face-to-face with Buddha, a Florida panther, dozing in the corner of his nighttime quarters–a simple chain-link enclosure with a raised platform. As we walk up to his cage, Buddha becomes excited, pacing the concrete enclosure, stimulated by Suzie’s voice. As his oversized paws pad the ground, a deep purr emanates from his chest. Suzie scratches the back of his head.

“They’re the largest wild cats to purr,” she says.

Meeting Buddha, The Tallahassee Museum’s resident panther

Buddha is a 12-year-old 120-pound male Florida Panther, one of the largest and most charismatic animals at the Tallahassee Museum. Like most of the animals at the museum, he’s incapable of living in the wild. As a kitten, before arriving at the museum, he fractured his humerus, later receiving an injection of stem cells to heal the injury. Now, as part of his morning routine, Buddha gets laser therapy treatment via a wand that emits a low-level light to provide some relief to his inflammation, arthritis, and swelling. As Suzie and Chris wave the laser across Buddha’s thick fur, he lays on his raised platform, purring loudly.

After Buddha’s therapy, which lasts only a few minutes, I follow Suzie as she walks Buddha’s larger, daytime enclosure. A large live oak casts shade over the enclosure; resurrection fern that has turned brown in response to the recent dry spell traces its spindly limbs. Dried leaves crinkle beneath our feet as we walk.

We trace the perimeter, double checking that the enclosure doesn’t have any safety risks, and she points out some invasive plants that have reemerged, despite the ongoing efforts to eliminate them from Buddha’s home. (It’s a little bit of a relief to see that I’m not the only one struggling to keep cat’s claw and Chinese tallow at bay!) On a different morning, they’ll pull up these plants as they work to keep the enclosure as close to the panther’s native habitat as possible.

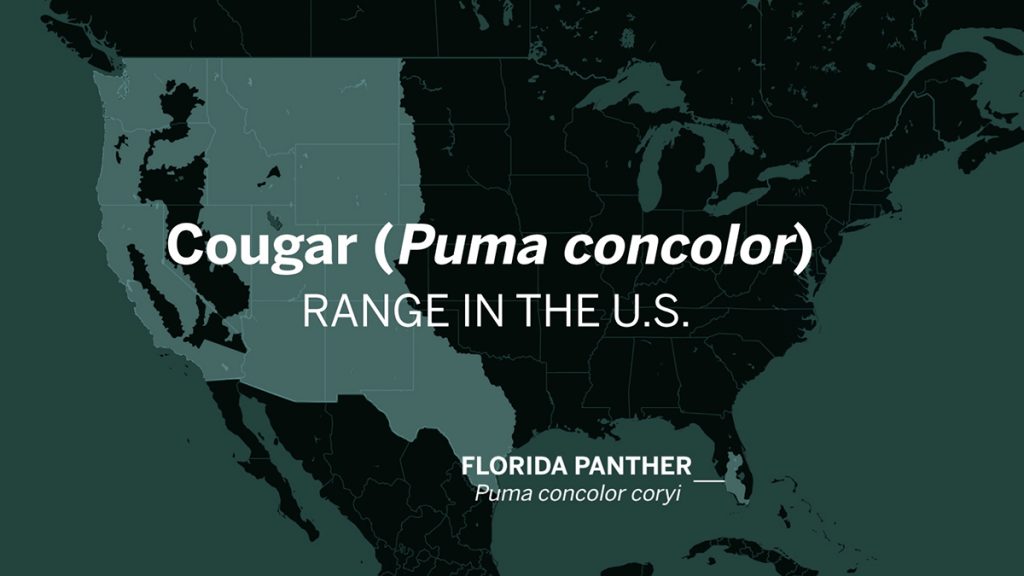

Currently, in the wild, Florida panthers typically frequent more wet and swampy habitats than this dry upland forest that has been enclosed for Buddha, but this ecosystem of live oaks and dwarf palmettos that is familiar to North Floridians was once just as familiar to the Florida Panther. While the Florida Panther now exclusively lives in Southwest Florida’s everglades, its range once included all of Florida, as well as Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and the lower half of South Carolina. Where the Florida panther’s range ended, other subspecies of cougars lived in adjacent ranges, such as the eastern cougar and the Texas cougar. Now, apart from the Florida panthers, cougars exclusively live on the west coast, where they are called by several interchangeable names: pumas, mountain lions, cougars.

Animal Enrichment at the Museum

As we walk through the enclosure, Suzie carries a basket full of seasonings, perfumes, and animal byproducts–musky colognes, coyote and rabbit urine, chili powder, fox fur, and sheep wool. She sprinkles curry powder over some dried leaves, the bright yellow seasoning a stark contrast to the loamy earth. We walk a few feet, and she sprays a purple-hued perfume onto a tree, the sweet floral scent filling the air.

These scents are part of their enrichment. As we’ve previously covered in the blog, the Tallahassee Museum works to keep its animals as wild as possible through enrichment that stimulates their wild instincts. This keeps the animals healthier, and is especially important for animals like the Red Wolves, who are part of rerelease campaigns and may one day find themselves back in the wild where they will have to use these instincts.

Buddha will be stimulated and curious about any new smells or additions to his environment. Suzie likes to try out different scents, never knowing what he will respond to. Sometimes, the cats also get blood popsicles, she’ll hide chunks of meat around the enclosure, or she’ll bring in objects that were in the cages of the museum’s other animals, like the skunk or fox cages.

“The fox and the skunk—they usually stink up their dishes,” Suzie says, “and we take out their dirty dishes and the cats just love that smell. They rub their face in and drool.”

Today there were no blood popsicles or urine, but Buddha, surprisingly, is a big fan of Jamaican curry powder. When we leave the enclosure and Suzie releases Buddha, he walks the perimeter of his space, rubbing his nose in a clump of yellow powder.

The Florida panther’s history in our state

The Florida Panther’s story is not dissimilar to other apex predators within our state. Apex predators can struggle to adjust to environmental changes more than smaller animals. It’s very “expensive” to be big and it can be hard to find for big animals to find the resources they need as their environments shrink or change. Apex predators are also often extensively hunted and before restrictions were put in place, Florida panther populations were decimated by hunting. Apex predators can be hunted for many reasons, but often, humans see them as threats. Large mammals can take out livestock and many people will behead any snake that crosses into their yard, not thinking about the ways they contribute to the health of our ecosystems.

Several apex predators have become extirpated (which means locally extinct) in Florida or parts of Florida. Red Wolves, for example, were extirpated from the Florida panhandle, and likewise, the Indigo Snake disappeared from large swaths of its native ecosystem. Currently, the Indigo Snake is being rereleased on the panhandle as part of a multi-year campaign; a few months ago I partook in that release for the blog. The Red Wolf has also been rereleased on St. Vincent Island and we’ve covered the extensive work the Tallahassee Museum has done to help strengthen this apex predator’s presence in the southeast.

The Florida panther narrowly escaped extinction, shrinking to just 5% of its original habitat. In 1995, an estimated 30 Florida panthers remained in the state. Now there are upwards of 200. As the rest of the east coast cougars disappeared in the early 1900s, Florida panthers were able to survive by disappearing deep into the everglades where they still predominantly live.

The average person would have trouble differentiating the Florida panther from its western relatives. Suzie tells me that mostly the difference comes down to looking at the cat’s genetics, other than that, there are only small physical differences.

“The Florida Panthers skull is different–it’s like higher dome,” Suzie says. “If you look at a Western cougar, they have like a flatter head. But otherwise, you know, they look pretty much the same. Most people wouldn’t necessarily be able to tell the difference.”

The Tallahassee Museum has two Texas Cougars and one Florida panther, so if you visit, you can try to tell the difference between these two large cats. (I couldn’t.)

With such a low wild population, inbreeding was a major issue for Florida panthers. Florida panthers began to develop deformities such as kinked tails and cowlicks. In response, state officials introduced eight female Texas cougars to breed with the existing population of Florida panthers. When cougars lived across North America, the Florida panther and the Texas cougar would have naturally bred with one another and so, this campaign was a natural way to save the Florida panther from inbreeding issues. Male cougars have large ranges of 200 to 250 square miles and Florida panthers had established ranges that would have overlapped with Texas cougars.

The disappearance of apex predators can throw off an ecosystem balance

“Cougars are umbrella species,” Suzie explains. “So having them in our landscape helps protect plants and animals. Without them, for example, we have a less healthy deer population. Apex predators don’t often kill the biggest, most beautiful bucks. It’s easier to take out a weaker ones, which might have diseases. So, you know, without predators, the sicker and weaker animals without the best genetics continue to thrive and pass on diseases, putting the whole system out of balance.”

It’s not just the deer that are out of balance from a dearth of predators. Tick-borne diseases like Lyme disease are more prolific in out of balance ecosystems as ticks prey on mammals like deer. Without apex predators, Suzie also explained how non-native species can become invasive in an area as they, like the deer, can thrive unchecked. Wild hogs, for example, have taken over huge expanses of land in the southeast because of this issue.

As Suzie talked about the hogs, I thought about my frequent visits to St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge. When I walk deep into the Refuge, away from the main road that meanders towards the lighthouse, I commonly see families of hogs, or at the very least, paths, meadows, and forests completely rooted up from snouts searching for acorns and tubers. Wild hogs are not native to the southeast and this rooting behavior decimates local ecosystems.

While hunting from early European colonialists originally decimated huge numbers of panthers, currently, its biggest threats are habitat loss and vehicle accidents. (Florida panthers are a protected species and it is now illegal to shoot them.)

A big boon for the panther came in the form of the passing of the Florida Wildlife Corridor Act in 2021, which secured $400 million to protect interconnected natural areas in Florida. Rather than designating large swaths of new land, this act works to connect existing natural land, including timberland and ranchland, together so that wildlife can freely move around the state. The act also helps to fund wildlife passages so animals can more easily avoid crossing deadly roads. All of this creates larger habitats for animals, allowing panthers to more easily obtain the large ranges that they require.

Prior to passing this bill, state officials had already been working to create land for panthers. In 2012, the FWS and the US Department of Agriculture helped negotiate the sale of 1200 acres to a local rancher. Part of the deal involved putting the land in conservation easement, preventing future development of the land. In recent years, ranchers have become an important part of the conservation movement as the large swaths of land their cattle require can also serve as wildlife corridors or homes for struggling species like the Florida panther.

The hope is that by connecting these lands, the Florida panther population will continue to grow and expand their range. A major success occurred 2016 when a female panther was caught on tape crossing the Caloosahatchee River for the first time. Males venture further than females and have larger ranges (200-250 square miles in comparison to females’ 70 – 200 square mile ranges). Male Florida panthers have been observed as far north as St. Augustine, the panhandle, or even South Georgia, but females are never seen this far north. When trails cameras photographed a female panther crossing the Caloosahatchee River with kittens, it showed that the panther was moving north and claiming new territories.

Continuing Buddha’s enrichment

Before we leave the museum, Suzie hands me several of Buddha’s toys. They look like giant dog toys—purple and tan and made of thick plastic. They are punctured by deep teeth marks. We relocate from the backstage area to the boardwalk. The museum is open now and families walk the boardwalk as we watch Buddha from above. At Suzie’s direction, I hurl the toys over the chain-link fence and watch as Buddha bounds after them, sinking his claws, his teeth, into the hard surface. Within a few minutes, he has tired of these toys and retreats to his raised wooden platform. His habits, after all, aren’t that dissimilar from a common house cat. Cougars are the largest cats that purr and meow, and like most cats, will spend 18-20 hours a day sleeping. As my phone gives off an intense heat warning, I suppose he is especially interested in a relaxing cat nap.

Catching up with other animals at the Tallahassee Museum

WFSU Ecology producer Rob Diaz de Villegas likes to think that this red wolf is smiling because he’s happy to see him for the first time in a couple of years. Rainier is one of four red wolf pups born at the Tallahassee Museum in 2017, whose lives WFSU chronicled for a year. He is currently the breeding male at the Museum.

Have you figured out which cat is which in our face to face comparison up above?