“Whole lot of grape vines coming up after Hurricane Michael, taking advantage of the newly opened canopy,” says Lilly Anderson-Messec. Lilly is the Project Manager for Florida Native Plant Society’s TorreyaKeepers, and a big part of her job involves climbing into steephead ravines such as the one we’re in now.

TorreyaKeepers is trying to preserve the precious few Florida torreya trees left in the world. The tree’s range is small, limited to ravine slopes along a small section of the Apalachicola River. It’s one of many rare plant species that grow in these cool, moist, shaded spaces.

Now, after Michael, a few steephead ravines are seeing the sun. They’re also seeing grapevines, like those draped over trees pretty much everywhere else. When sun shines down where it once hadn’t, sun loving plants move in. For the foreseeable future, that’s going to change the plant community down here.

“We’re going to witness how this ravine recovers itself,” says Brian Pelc, Restoration Project Manager for The Nature Conservancy in Florida. This ravine is in TNC’s Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve. “We’re not going to actively try and recreate what it was. But there certainly will be some shifts, some winners and some losers.”

It could take a hundred years for new trees to grow large enough to once again darken the ravine floor. If we, and those who come after us, keep an eye on this spot, we’ll see the plant community here change, and change again. And if we zoom out and look at the surrounding habitats, and all along the Apalachicola River corridor, we’ll see how nature bounces back from the kind of major catastrophe that is becoming more common as the Earth warms.

To keep our posts focused, I’m writing two for this video. In this one, we’re looking the Apalachicola watershed and how it might adapt as the Earth warms. In our other post, we take a look at the many plants and animals that make the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines a top biodiversity hotspot.

Hurricane Michael | A Major Climate Event on the Apalachicola

“Hurricane Michael, the storm impacted the entire Apalachicola River system,” says Apalachicola Riverkeeper Georgia Ackerman. “It tore right up the river corridor, and we saw impacts to the entire basin that are still being assessed and measured.”

In the forty eight hours leading up to landfall, on October 10, 2018, the storm went from a Category 2 to a Category 5. This kind of rapid intensification of hurricanes is becoming common, the result of a warmer climate.

“Hurricanes, they’re natural,” says Doug Alderson, Outreach and Advocacy Director for Apalachicola Riverkeeper. “They’ve been occurring for millions of years. But because of climate change, hurricanes are increasing in intensity. They’re increasing in the number of hurricanes.”

NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Lab outlines how climate change is affecting hurricanes. More storms, more strong storms, more rain during storms, and more destructive storm surge. The Apalachicola basin is also dealing with other climate change effects such as drought and sea level rise.

Hurricane Michael was one event, but the way it hit every part of the river system, it has a lot to tell us about the future of the Apalachicola River basin.

Building Future-Ready Ecosystems

Currently, we’re standing in a field of future. We’ve visited this section of Torreya State Park before on the Ecology Blog. Here on the Sweetwater Creek Tract, The Nature Conservancy is helping the park restore fire dependent longleaf/ wiregrass habitat.

There are over a dozen restoration zones in the 4,000+ acre project, all in different states of progress. This one is a giant field of grass. What longleaf pine we see is still in the grass stage, its youngest stage of development. We see plentiful wildflowers, and Lilly spots some of the rare species that define this region’s biodiverse reputation.

This is a restoration, an attempt to return the land to what it had been. Longleaf pine used to cover the American southeast, but only 5% of that habitat remains. As I often hear when doing longleaf restoration stories, it will take hundreds of years for the habitat to become what it once was.

But can that really be the goal? With the world warming, we can’t expect it to return to exactly what it had been, can we?

“One of the questions that we get a lot in the context of climate change is, how do we know what we’re aiming for?” Brian says. “How do we keep up with the changes that are happening in the plant community as the climate changes?”

The answer, to The Nature Conservancy, is to focus on ecosystems as a whole.

“We’re not necessarily aiming to conserve individual plants. We’re thinking of it like actors on a stage. And our goal is to conserve the stage, so that whatever movement of actors across the stage happens because of climate change, it will still be here to function that way.”

The stage is being set, but how will it play out?

The idea is that an intact ecosystem will more effectively respond and adapt to change. Resilient. In a high, dry sandhill, that likely means pine needles and grasses will still carry fire. The fire, in turn, will still create an open understory where woody plants remain shrubs, and a diversity of wildflowers and herbaceous plants have space to thrive. They just might not be the exact plants we would expect to see here now.

Having that one resilient location, which filters and feeds water to the river, is beneficial to the Apalachicola. Having a network of different connected ecosystems makes a resilient region. The Apalachicola River corridor has just that.

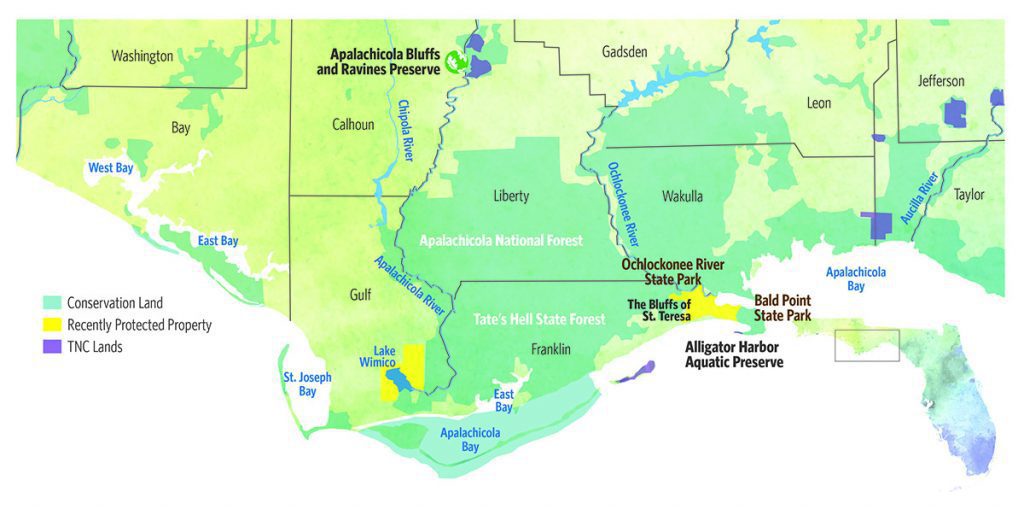

“So many entities, ourselves and others, have been working to put that patchwork quilt, if you will, together over the years.” Says Temperince Morgan, Director of the Nature Conservancy in Florida. Temperince touts two recent successes towards this end, new land acquisitions in and around the Apalachicola watershed. Lake Wimico and the Bluffs and Saint Teresa are now, with the help of The Nature Conservancy and its partners, part of a connected network of protected lands spanning over a million acres.

“We know some species will be able to relocate as a result of climate change impacts to new homes within their… local resilient neighborhood.” Not only will plants and animals be able to migrate unimpeded, but coastal systems like marshes and dunes can move upwards as sea level rises.

Resilient and Connected Landscapes

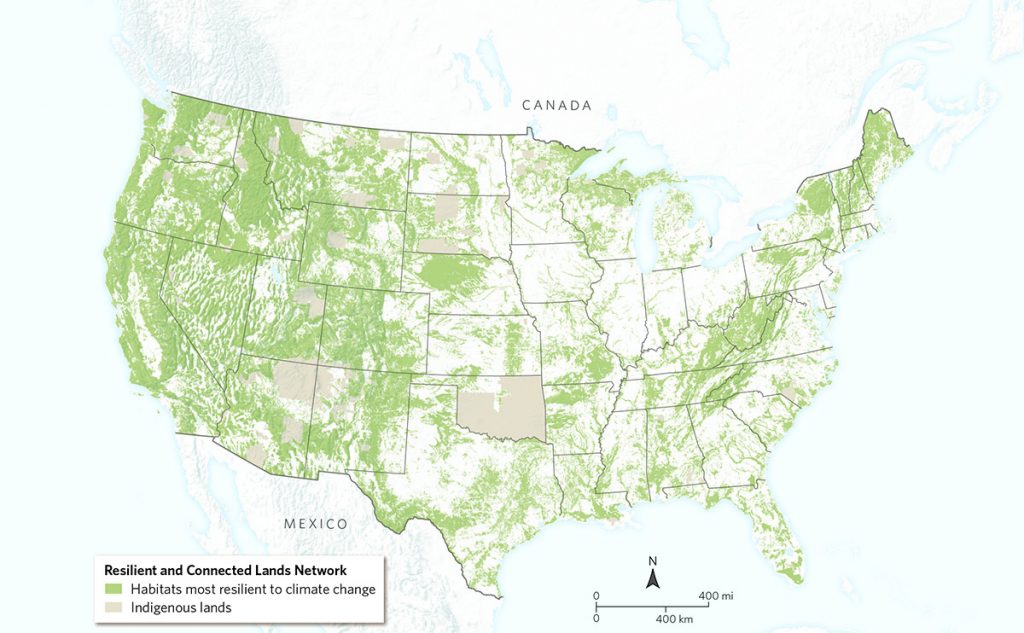

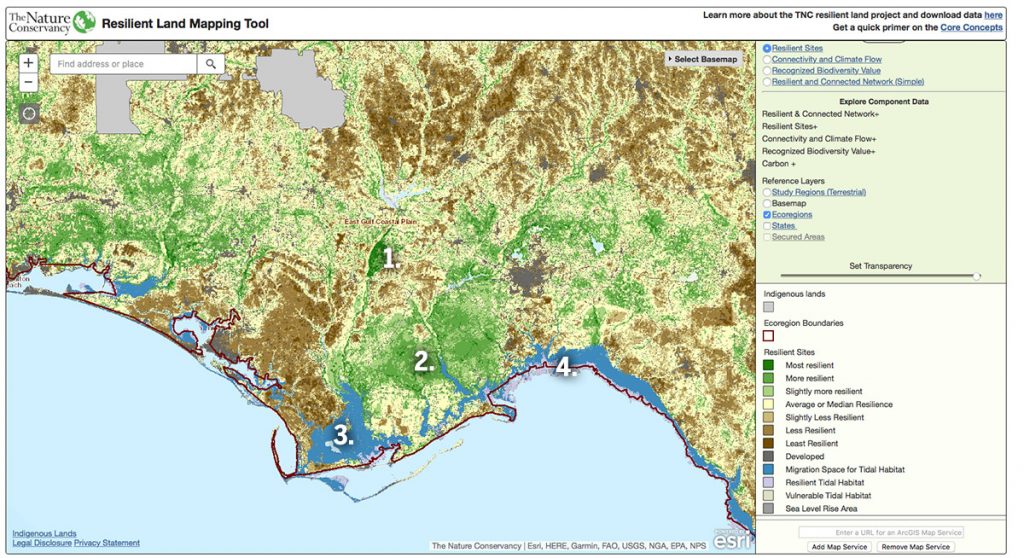

Having the space to move is one factor. But, according to researchers at The Nature Conservancy, the Bluffs and Ravines region in particular has a favorable geology for plants and animals in a warming world. They recently created the interactive Resilient and Connected Landscapes mapping tool, which highlights networks of connected lands and corridors.

According to The Nature Conservancy, “The scientists found that landscapes with diverse physical characteristics – such as steep slopes, tall mountains, deep ravines and diverse soil types – create numerous microclimates that offer plants and animals the opportunity to move around their local ‘neighborhood’ to find suitable habitat where they can escape rising temperatures, increased floods or drought.”

The Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve may not have tall mountains, but it does have steep slopes and deep ravines. Says Temperince Morgan, “A site like ABRP has a lot of potential to provide resilience because it has a lot of micro-topography, and can provide a lot of niche habitats in a small space.”

We can’t predict exactly what resilience will look like, both in terms of how a steephead ravine might recover from a strong hurricane, or what climate refugees might seek shelter within it. Less predictable still is how the watershed as a whole will respond in the coming years. But between recent droughts and Hurricane Michael, we can start to get a sense of some of the challenges ahead.

How is the Apalachicola watershed recovering after Michael?

Two years after Michael, many ecosystems along the Apalachicola River are still visibly damaged. On more than one video shoot, we’ve seen landscapes full of broken trees, and plentiful open spaces where trees had been. On the coast, beaches are lined with stumps that had once been inland trees- evidence of sea level rise.

The following are observations from shoots where we’ve seen hurricane damage, or other climate effects in action.

Deforestation and Drought in Torreya State Park

The storm did some damage to The Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve, as we saw in the ravine. But, just to the north, Torreya State Park seems to have taken a direct hit. The park’s 14 miles of once shaded trails are now in full sun. The park has cleared fallen trees, but those that remain are visibly damaged. Park Manager Jason Vickery estimates that every tree in the park was damaged to some extent.

Two harsh droughts in 2019 further stressed the injured trees. Jason worried that the dry conditions, along with all of the debris still on the ground in October of 2019, put the park at risk for a dangerous wildfire. For that reason, the park had to spend time in its recovery effort clearing fire breaks around its boundaries, especially where it borders residential areas.

The driest, most likely places to burn in our area are managed with fire. Southeastern longleaf pine systems are burned every 2-5 years, which keeps the amount of available fuel on the ground manageable. Hurricane Michael knocked down a considerable number of trees over a wide area, which in some cases (as at Torreya) took over a year to clear.

Dominant Trees on the Chipola River

In November, Doug Alderson and I kayaked ten miles of the Chipola River, the main tributary of the Apalachicola. Here, we saw similar tree damage to that in Torreya. The thing that stuck with me afterwards was something that Doug pointed out.

Despite the visible deforestation around us on the water, Doug said, “I’ve noticed some of the trees that made it, especially some of the cypress and the live oaks, seem to be doing really well. They’re going to end up being some very dominant trees.”

In the ravine, Brian mentioned that there would be winners and losers on the newly sunny ravine floor. Trees with strong wood and wind resistant limbs are the winners when intense storms roll through. These are the trees that will survive and pass on their genes. And again, the shadier bottomland forests around the river are seeing more sun on the ground, which will affect what grows there.

Last year, we produced a segment on live oaks and Tallahassee’s urban forest. Tallahassee’s Urban Forest Master Plan was created as a guide for improving the quality of Tallahassee’s canopy; and a top criteria in determining a high quality tree, especially in light of a trend towards stronger storms, is a species’ resistance to strong winds. Both live oaks and bald cypress are in the top tier of storm resistant trees, trees that pose the least danger near structures and power lines.

The plan doesn’t recommend planting only these species of tree. Ecologically, diversity is still important. But we see that strong storms are influencing the urban planning process as well as natural selection.

Sea Level Rise and the Barrier Islands of Apalachicola Bay

Apalachicola Bay is enclosed by Dog Island, Saint George Island, and Saint Vincent Island.

“Think of them as kind of like a fence, holding the fresh water in a little bit,” Doug Alderson says. “So the fresh water leaks out slowly, and it helps create this incredible mix, this estuary. It feeds a lot of fresh water into the Gulf, too, that affects fisheries all the way to Tampa.”

That’s when fresh water flows from the dam, of course.

Michael leveled dunes across this chain, and broke through sections of nearby Saint Joseph Peninsula. Those breeches did fill themselves after a time, but it can take decades for large beach dunes to form.

Earlier this year, we visited Saint Vincent Island with Florida State University oceanographer Dr. Jeff Chanton. He’d been measuring the effects of gradual sea level rise on the island when Michael destroyed his instrumentation, along with much of the island’s primary dune system.

As he he explained then, large storms accelerate gradual sea level rise. “Shoreline erosion is episodic. It goes along, goes along, goes along, and all of a sudden it will happen in a big way. And that big way is associated with a hurricane.”

Highway 98 and our vulnerable coastal infrasctructure

Jeff also showed us spots in Franklin County where Highway 98 was washed away in the storm. A large stretch of this scenic highway hugs the coast here, protected by hard armoring- sea walls and rip rap. Given the frequency of storms that send surge over the armoring, and the frequency with which the road needs repair or rebuilding, Jeff said, “I think it’s one of the more important, vulnerable places along our coast here.”

WFSU-FM’s Robbie Gaffney accompanied Jeff and I that day. Robbie revisited US 98’s storm resilience in a story about a $15 million project to create a living shoreline along the road in Franklin County. The Apalachee Regional Planning Council is currently testing different materials to see which would best attract oysters.

When oysters establish themselves on a hard substrate, they begin to form a reef habitat. “So as the waves hit the reef, it slows them down and reduces the amount of actual energy that’s there,” explains ARPC’s Josh Adams. Once the waves slow, the hope is that salt marshes start to grow behind the reefs. Oyster reef and salt marsh habitats, aside from sheltering a wealth of commercially important species, hold sediment and prevent erosion.

ARPC realizes that, while these intertidal ecosystems slow wave action, they’ll be inundated by storm surge from hurricanes Category three or higher.

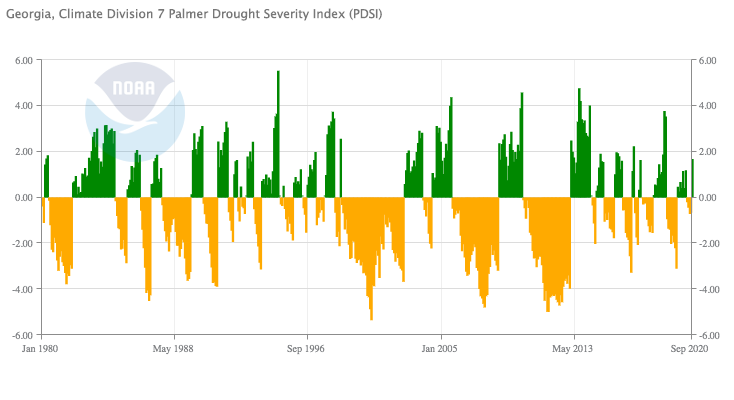

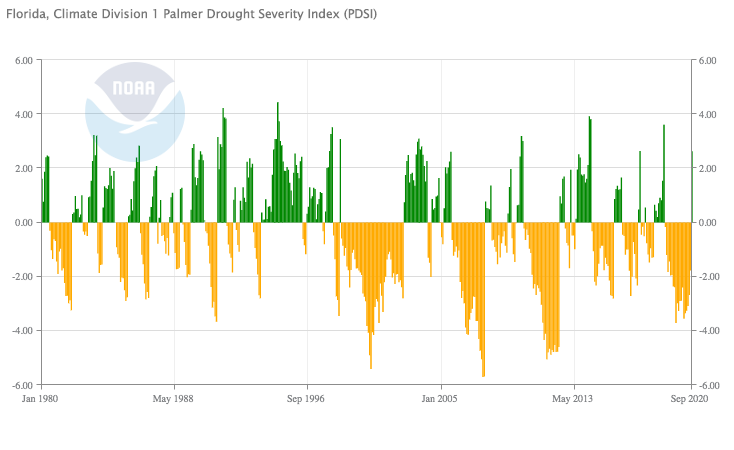

Drought in Georgia, Low Flows on the Apalachicola

Harsh droughts have had a major effect on the Apalachicola River and Bay. The Apalachicola Bay oyster fishery crashed during a prolonged 2012 drought; eight years later, there is still not enough oyster stock to sustain a fishery. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission is closing the bay for five years to allow reefs to regenerate.

Since the river flows from the Woodruff Dam at the Florida/ Georgia Border; the system can’t respond naturally to drought. The Army Corps of Engineers manages the river flows, guided by a Water Control Manual for the Apalachicola/ Chattahoochee/ Flint River system. Per the manual, when there’s drought in Georgia, the Corps keeps water in the Flint and Chattahoochee River systems.

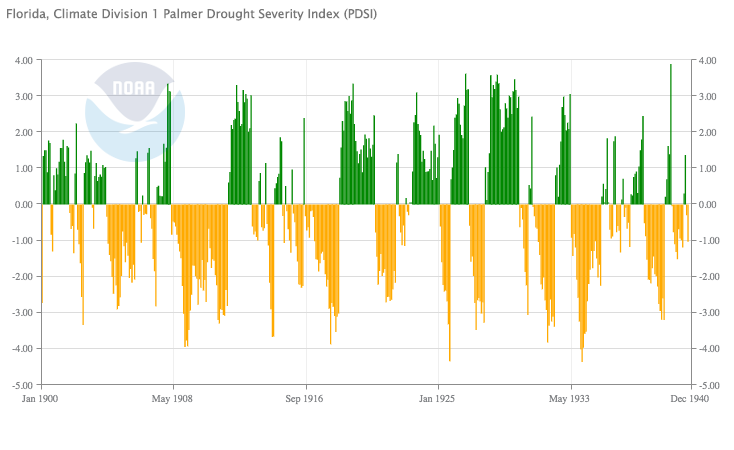

Palmer Drought Index for northwest Florida, 1900-1940

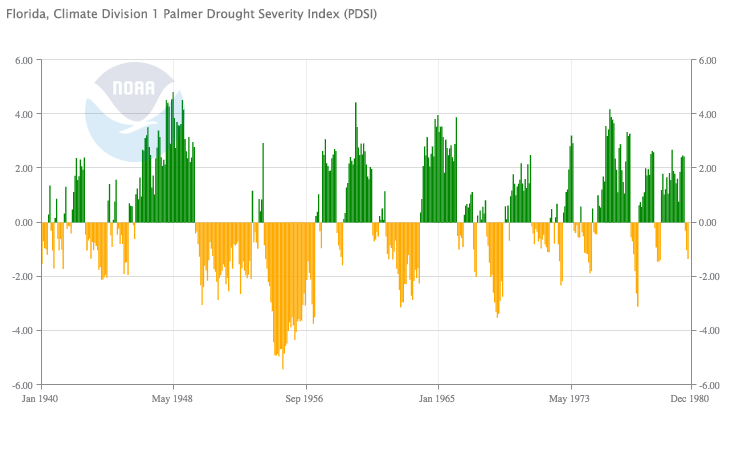

Palmer Drought Index for northwest Florida, 1940-1980

The altered river flows have famously affected Apalachicola oysters. Restricted flows, along with the Corps’ modifications of the river channel, have also caused the loss of over four million trees in the Apalachicola floodplain. Less water has been making into swamps in the river system, with the dam sometimes sending the minimal allowed flow during the critical growing season. Between 1978 and 2006, swamps connected to the river lost over 40% of their tupelo trees. Tupelo swamps are a critical source of nutrients for the bay, and the nectar source for the world famous Tupelo honey.

A lawsuit between Florida and Georgia over the system’s water is set to be heard by the US Supreme Court. Additionally, Apalachicola Riverkeeper has submitted a legal challenge the Water Control Manual, which was recently revised to allow less water to the Apalachicola during droughts.

Lake Wimico and The Bluffs of Saint Teresa | Building the Network

These two recent acquisitions add 37,000 acres of protected land to our region.

Lake Wimico is just northwest of the city of Apalachicola, and connects to the Apalachicola River delta via the Jackson River. According to The Nature Conservancy, “The conservation of the cypress-dominated swamps, marshes and water flow help ensure a resilient landscape that provides adaptation to impacts of climate change and sea level rise, and habitat for ecological communities.”

The Bluffs of Saint Teresa is a 17,000 acre parcel that closes a gap between state and federal lands. It protects some of that coastal habitat along US 98 in Franklin County, as well as the southern shores of Ochlockonee Bay. And it connects Bald Point State Park to Ochlockonee River State Park, Tate’s Hell State Forest, and the Apalachicola National Forest.

In this map provided by The Nature Conservancy, you can see the extent to which conservation lands are connected. It’s land that protects coastline, rivers, wetlands, and longleaf forest. A lot of this is habitat that needs to be restored, or is in the process of being restored- the stage not yet set. But the stage is getting bigger.

Looking Ahead

Whether or not the stage is set, the play is underway. We’ve met some of the actors. Wind resistant trees and grape vines. Oysters that need more fresh water. Coastlines on the move.

Land acquisitions and habitat restoration projects promise to make the changes to come a little easier. But Hurricane Michael showed that those changes can come quickly and violently. Resiliency doesn’t necessarily mean that the punch doesn’t hurt. It means you get up more quickly after you were knocked down.

We’ll keep revisiting restoration sites to see how they progress. We’ll also keep checking on the areas that are healing after Michael. Our natural systems are in a time of change, and despite our efforts to restore and manage them, there’s no predicting how they’ll turn out.

Click the points on the map to read WFSU Ecology Blog and WFSU News stories about Hurricane Michael’s ecological impact on the Apalachicola River corridor.

The Age of Nature on WFSU

Age of Nature on WFSU has been funded by a grant from PBS. We’re examining the Apalachicola River basin using the themes at the core of the PBS special series, Age of Nature.

- In our first video, we look at how healthy uplands affects habitats below, sending ripples through the river system.

- For our next video, we have two blog posts. This one looks at climate resiliency in the Apalachicola watershed, while another looks at the many species that make the Bluffs and Ravines a biodiversity hotspot.

- We hosted a one hour discussion on the future of the Apalachicola with an all star panel of conservation leaders. We also explored the Bluffs and Ravines in a thirty minute Virtual Field Trip.

You can stream the PBS series Age of Nature on wfsu.org through November.