Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

Slideshow: Army Corps of Engineers visit Apalachicola Bay

Tonight on WFSU’s Dimensions: Part 1 of the RiverTrek 2012 Adventure. Days one and two of paddling, camping, hiking and climbing air at 7:30 PM/ ET with an encore on Sunday, October 28 at 10 AM/ ET. The trip concludes with Part 2 (Days 3-5) on Wednesday, November 14 at 7:30 PM/ET.

The slideshow above was photographed on Monday, when Army Corps of Engineers colonels were invited (along with state agency officials and media) to see firsthand how depleted the oyster reefs in Apalachicola Bay have become. We went out in three oyster boats, captained by the leadership of the Franklin County Seafood Workers Association, to the Cat Point bar. Cat Point is usually one of the most productive winter reefs in the bay. In early September, the Summer reefs closer to the mouth of the river are closed and the Winter reefs further out are opened up. The Winter reefs should have spent months replenishing and younger oysters should have matured into legal sized, commercially viable oysters. Only this year, it didn’t happen.

Shannon Hartsfield, President of the Association, takes a few licks with his oyster tongs and then hands the them to Colonel Donald Jackson. Colonel Jackson takes a few licks; between the two of them they take about eight. Hartsfield inspects their catch: about six legal oysters in a pile of dead shell. Later he tells me that in past years, that amount of work would have yielded about a 30 lb. bag of legal oysters. This is what the Army Corps of Engineers colonels were invited to see. The Corps controls the flow of water in the Apalachicola/ Flint/ Chattahoochee basin, directing water into over 200 reservoirs and adjusting how much flows through dams. The lack of water flowing from the Apalachicola River, due in large part to the drought we’ve experienced over the last couple of years, is the main cause of the fishery crisis. The oystering demonstration is the Franklin County Seafood Workers’ argument for more water to be allowed through Woodruff Dam at the Florida/ Georgia border.

The wrangling over this water is often portrayed as between seafood workers in the bay and Georgia’s farmers and Atlanta’s water consumers. But the list of stakeholders also contains power companies (hydroelectric and nuclear), MillerCoors LLC, manufacturers, and recreational concerns, to name a few (see the full list here). It’s messy. And change doesn’t look like it’s coming soon. As the colonels said during the community meeting later that night at the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve, they are soldiers following a protocol. A new protocol (an update to the ACF Master Water Control Manual) is being drawn up, but changes will not take effect for 2-3 years, and in the meantime there isn’t a lot of leeway for how the water can be redirected, at least not by the Army Corps of Engineers’ authority (The U.S. Legislature grants them the authority they have). They are taking public input for the Manual Update, you can send your comments here.

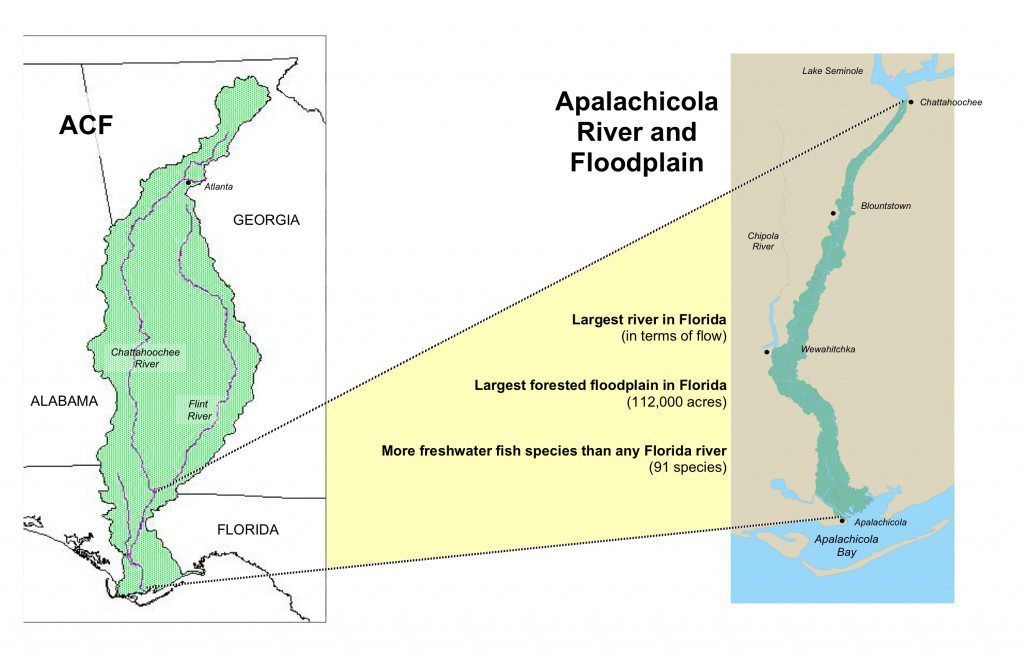

This slide provided by Helen Light (©USGS) illustrates the floodplain supported by the river. As water levels have decreased over the last few decades, there has been a loss of 4 million trees in the floodplain and a loss of aquatic habitat.

During that meeting, presenters from different agencies, universities, and local concerns laid out the impact of the low water flow on the bay and on the river basin. The next day, the colonels would be going up the river to see the effects of low flow there, where I had just paddled a week-and-a-half ago in the video that airs tonight. My interest had been, as a main focus of the In the Grass, On the Reef project is oyster reef ecology, the bay and how the lack of river flow had affected it. As Helen Light said to us on the first night of the trek “You all know a lot about the bay, and the impacts in the bay, you’ve been reading it in the paper.” That night, gathered around her on the sand bar across from Alum Bluff, she proceeded to tell us about the effects on the river. She had studied the floodplain for decades while working for the US Geological Survey, and has seen the changes undergone as river flow has decreased over the last few decades. I keep going back to her talk in the video, much as we did in our conversations kayaking down the river. Even as we were falling in love with the river (or reconnecting with it), we learned of its struggles and the troubles it was facing.

For all of the statistics on the decline of the river, it was still a beautiful paddle. The fish were jumping, eagles soared overhead, turtles sat on logs- and as we reported, there were plenty of snakes. We got off the river, too, to see some of the creeks, swamps, and forest around it. For all its troubles, the river is still enjoyable, as are its products. There has been a 44% decline in Ogeechee Tupelo trees along the river since 1976, but you can still buy tupelo honey produced from the trees in the river basin. And at the reception after the community meeting on Monday, the same day I saw oystermen pull dead shell off the floor of the bay, there were trays of healthy looking Apalachicola oysters on the half shell. As tourists and consumers, it can be easy to dismiss the stats when our own eyes (and taste buds) tell us everything looks normal.

For all of the statistics on the decline of the river, it was still a beautiful paddle. The fish were jumping, eagles soared overhead, turtles sat on logs- and as we reported, there were plenty of snakes. We got off the river, too, to see some of the creeks, swamps, and forest around it. For all its troubles, the river is still enjoyable, as are its products. There has been a 44% decline in Ogeechee Tupelo trees along the river since 1976, but you can still buy tupelo honey produced from the trees in the river basin. And at the reception after the community meeting on Monday, the same day I saw oystermen pull dead shell off the floor of the bay, there were trays of healthy looking Apalachicola oysters on the half shell. As tourists and consumers, it can be easy to dismiss the stats when our own eyes (and taste buds) tell us everything looks normal.

1 comment

[…] has to do with clean (or cleaner, anyway) water. I wrote last week about the Army Corps of Engineers visit to Apalachicola Bay, and the meeting during which various […]

Comments are closed.