Episode 4: The Hidden Value of an Oyster Reef

Weeks ago, we came up with a schedule for posts and videos and somehow had our video on oysters due for the week after Governor Scott declared this year’s oyster harvest a failure. This led to one minor alteration in the above video, but the video was meant as an overview to the services provided by oyster reefs. There will be content related specifically to Apalachicola Bay in the coming weeks.

Dr. David Kimbro FSU Coastal & Marine Lab

There are a lot of things that a marine scientist can study such as charismatic animals (dolphin and turtles) or the waves and currents that fuel my surfing addiction. So, why do I spend most of my time mucking around in mud to study the uncharismatic oyster?

There are a lot of things that a marine scientist can study such as charismatic animals (dolphin and turtles) or the waves and currents that fuel my surfing addiction. So, why do I spend most of my time mucking around in mud to study the uncharismatic oyster?

Short answer: because they can provide the foundation for a lot of things that we depend on. Now, some of these benefits or services are obvious and many others aren’t.

Let’s start with the obvious. Just like raising cattle supports tons of jobs and our appetite for hamburgers (I recommend reading Omnivores Dilemma if you want to see how eating meat can be environmentally friendly), the harvesting of oysters financially supports many folks as well as the scrumptious past time of tasting oysters on the half shell as the above video just showed me doing at my local favorite, the Indian Pass Raw Bar!

Unfortunately, the importance of this service was made all to clear to us when the Florida governor recently declared this year’s harvest to be a failure and applied for federal relief for the local economy (Download a PDF of the Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services report here). It’s also unfortunate that this type of bad news has a history of indicating that this natural resource is in trouble and that more trouble may be on the way. To see why, check out a study by Dr. Michael Kirby that showed how this service progressively collapsed from New England down to Florida over the past three centuries. In a nutshell, the pattern of collapse mirrors the increasing number of humans that have over-used this service.

But even if there are no questions about the importance and collapse of the previous service, many folks are asking great questions about whether oysters provide other important services in the form of protected reefs that may offset or exceed their commercial/restaurant value. In other words, what good are oysters to us if they don’t make their way to the raw bar?

Well, my good buddy Dr. Grabowski’s research used relatively tiny oyster reefs to highlight one less obvious service that involves reefs really ramping up the numbers of commercially and recreationally important fishes (drum) and crabs (stone crabs and blue crabs)….yum! Given that the oyster reefs used to be 12 feet tall and as long as football fields, can you imagine how many crabs and fishes hung around those really big reefs way back then? Heck, even I could have caught a fish!

Another thing that charismatic and good tasting animals need in order to keep our eyes and tummies happy is some healthy coastal water. Having too much plant-like material (phytoplankton) floating around in the water, sinking to the bottom, and decaying can deplete all of the water’s oxygen. Because such a place is very uninviting for lots of sea life, low oxygen areas will not have many animals that are pleasing to the eye, the fishing rod, or our palette.

Enter the filter-feeding oyster.

While it’s hard to know if today’s tiny amount of oysters reefs sufficiently filter enough water, we do know that the really big reefs of our grandparents and their grandparents time were essentially like huge skimmers in swimming pools as big as the Chesapeake Bay.

As the ESPN football talking heads like to say: C’mon Man! Really?

I kid you not, because Jeremy Jackson and colleagues dug through some Chesapeake mud to figure this out for us. Preserved in the mud is stuff that settled out from the water over time, with deeper mud containing older stuff and shallower mud containing newer stuff. It turns out that as we over-ate and turned the larger oyster reefs into small ones, the stuff in the mud transitioned from sings of healthy water to symptoms of unhealthy water. And because the oyster crashes came before the drop in water quality, it’s more likely that oysters maintained the good water signs as opposed to the reverse scenario of the good water signs maintaining the big oyster reefs.

So this points to a third type of service that oyster reefs CAN provide in the form of water-quality. Admittedly, it’s hard to put a dollar amount on that as opposed to the dollar amount that a dozen raw oysters brings in at a raw bar.

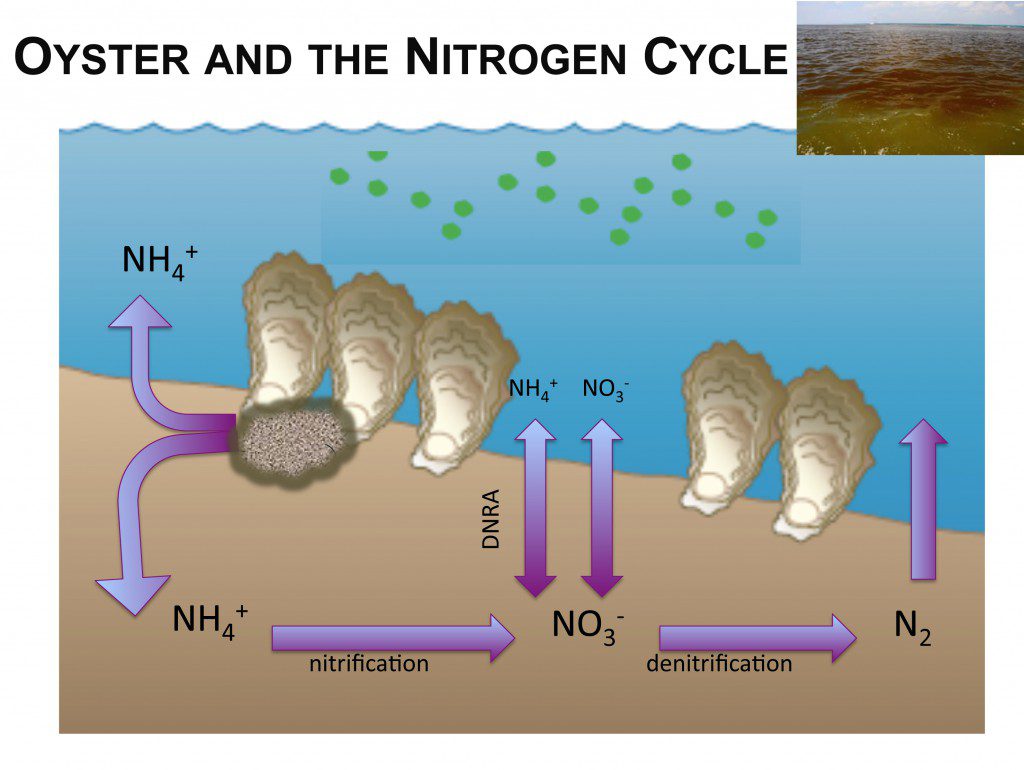

But another less obvious way that oysters can help maintain water quality is by removing the nutrients that a lot of the unwanted phytoplankton depend on.

C’mon Man!

You see, after oysters suck in the water, filter out their preferred phytoplankton (some are good, but some probably taste as bad as my poor attempt of making southern biscuits), they eventually “poop” their waste out into the mud. Some of this waste makes all sorts of bacteria do all sorts of different things. One of these cool things involves taking a form of nitrogen (think fertilizer on your lawn) that is readily sucked up by nasty phytoplankton and converting it into a form that phytoplankton can’t use (think bad fertilizer that you want to return for a refund). This is called de-nitrification, and it’s a way that oyster feeding and pooping can help maintain healthy coastal conditions. Even cooler, we can slap a dollar amount on it if we think about how much money it costs a waster-water treatment facility to remove the same amount of nitrogen. My buddy in North Carolina Dr. Mike Piehler did just a study and found that the value of this service is about 2,718.00 dollars per acre of oyster reef. And unlike a dozen raw oysters, this service keeps on giving like the energizer bunny.

Finally, and we are now at service 4 in case you are counting, oyster reefs can buffer the waves and storms that eat away at our shorelines, coastal roads, and homes.

Before signing off, I have to also acknowledge that not every oyster reef performs each of these services. Just like my brother and I look pretty darn similar to someone outside of my family, when you look closer, we are really different. Individual oyster reefs are the same way. Heck, while I can do different things well if you catch me in the morning with a cup of coffee, I often really stink at those same things if you check in with me after a too big and sleep-inducing lunch!

Before signing off, I have to also acknowledge that not every oyster reef performs each of these services. Just like my brother and I look pretty darn similar to someone outside of my family, when you look closer, we are really different. Individual oyster reefs are the same way. Heck, while I can do different things well if you catch me in the morning with a cup of coffee, I often really stink at those same things if you check in with me after a too big and sleep-inducing lunch!

This point segues nicely into my research interest about the “context-dependency” of the obvious and not so obvious services that coastal habitats can provide. In other words, why are some reefs doing some services but others are not? This question really crystallizes the essence of a collaborative project that I’m working on with colleagues from FSU, Northeastern University, University of North Carolina, and University of Georgia.

In our crazy-fun, at times maddening, and democratic research team, we are testing whether the answer depends on differences in big hungry and scary predators like drum and crabs lurking around the reefs. Sure, some of these might eat an oyster that doesn’t make it on to my plate at the raw bar. But overall, they may benefit some reefs by eating a lot of the smaller crabs that really like to munch on oysters. And even if they don’t eat all of these oyster munchers, we’re thinking that their presence may sufficiently freak out oyster munchers so that they spend more time watching their backs and less time munching. Hence, the ecology of fear!

Thanks for wading through this long post. If I promise to write shorter posts in the future, then I hope you’ll follow our journey of testing whether predators help maintain services not only in oyster reefs, but also in the marshes and mudflats of the southeast Atlantic and Gulf coastlines.

Cheers,

David

In the Grass, On the Reef is funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation

5 comments

How effective are oysters at limiting phytoplankton communities by de-nitrifying their nutrients (NO3 => N2)? As you know, some phytoplankton, such as cyanobacteria, are able to convert elemental nitrogen back into NH3 through nitrogen fixation. The slide you provided also shows NO3 being released into the water along with N2, which would add to the nutrients available to the phytoplankton. Some of the nastier algal blooms contain these cyanobacteria, like Microcystis aeruginosa, so are oysters really that effective at improving water quality by removal/conversion of nutrients?

Hey Chris

This is a great question and it definitely brings up the whole issue of context dependent services.

I’m without computer for the weekend (anniversary in New Orleans!). So, I’ll answer your questions tomorrow evening

Cheers

David

Hey Chris,

Following up on your great questions, which i’ll divide up into smaller Q/As.

(1) How effective are oysters at limiting phytoplankton communities by de-nitrifying their nutrients (NO3 => N2)?

Answer = the study i cited didn’t look at the effects of how well this service limits the population growth of phytoplankton, which would be a serious undertaking. But as a first step along this journey of exploration, they did test whether oysters really do ramp up the first ingredient of this hypothesis….de-nitrificaiton. Based on the great study, I can say unequivocally that even small clumps of oysters can ramp up de-nitrificaition. How this influences or does not influence phytoplankton remains to be seen.

(2) As you know, some phytoplankton, such as cyanobacteria, are able to convert elemental nitrogen back into NH3 through nitrogen fixation.

Answer: you thought about the influence of n-fixers is correct. But again, the study i mentioned only focused on the first step in this service, so I can’t really address this question.

(3) The slide you provided also shows NO3 being released into the water along with N2, which would add to the nutrients available to the phytoplankton.

Answer: I totally agree. but given the complexity of this dynamic and the many possible pathways by which nitrogen may get off the de-nitrification path and go back into a useable form in the sediment or the water, isn’t it cool that the study STILL found a huge effect of oysters on the rate of de-nitrification!

(3) Some of the nastier algal blooms contain these cyanobacteria, like Microcystis aeruginosa, so are oysters really that effective at improving water quality by removal/conversion of nutrients?

Answer: again, this remains to be seen. And like the other services mentioned in this post, I imagine that some environmental conditions will promote this service more than other sites or environmental conditions. We just have to figure that out.

Thanks for the great questions!

[…] always a good shoot day at Bay Mouth Bar as every animal seems to be eating every other animal. Oyster reefs, salt marshes, and seagrass beds- the habitats we’ve covered over the last three weeks- […]

[…] of the three estuarine habitats that we follow: oyster reefs, salt marshes, and seagrass beds. We saw that oysters offer more to the seafood industry than their meat. And we’re starting to see […]

Comments are closed.