Episode 7: Where Everything is Hungry

(Some species names have changed.)It’s always a good shoot day at Bay Mouth Bar as every animal seems to be eating every other animal. Oyster reefs, salt marshes, and seagrass beds– the habitats we’ve covered over the last three weeks- reward those who take the time to look closely. At Bay Mouth Bar, everything is all out in the open. For a limited time, anyway…

Dr. David Kimbro FSU Coastal & Marine Lab

Like most kids, I spent a lot of my formative years in the backyard practicing how to throw the game-winning touch down pass, to shoot the game winning three-pointer, and to sink the formidably long putt. Although my backyard facilities obviously didn’t propel me into the NFL, NBA, or PGA, they never closed, required no admission fee from my pockets (thanks Mom and Dad!), and were only a few steps away.

Like most kids, I spent a lot of my formative years in the backyard practicing how to throw the game-winning touch down pass, to shoot the game winning three-pointer, and to sink the formidably long putt. Although my backyard facilities obviously didn’t propel me into the NFL, NBA, or PGA, they never closed, required no admission fee from my pockets (thanks Mom and Dad!), and were only a few steps away.

Now that I’m striving to be an ecologist at Florida State University, I’m feeling pretty darn lucky about my backyard again. Instead of spending tons of time flying, boating, and driving to far away exotic places, I can use a kayak and ten minutes of David-power to access some amazing habitats right here along the Forgotten Coast.

Part of this coastal backyard was first intellectually groomed by one of the more famous and pioneering scientists of modern-day ecology, Dr. Robert Paine. Five decades ago, Dr. Paine noticed that the tip of Alligator Point sticks out of the water for a few hours at low tide. Of course, this only happens when the tides get really low, which happens about 5 days every month. But when the tip of Alligator Point (which is locally called Bay Mouth Bar) did emerge from the sea each month, Dr. Paine saw tons of large carnivorous snails slithering around a mixture of mud and seagrass. When I first saw this place, my eyeballs bulged out at the site of snails as large as footballs!

Fast- forward 2 decades later: Dr. Paine is developing one of the most powerful ecological concepts (keystone species), one that continues to influence our science and conservation efforts to this very day. Using the rocky shoreline of the Pacific North West as his coastal backyard, he is showing how a few sea stars dramatically dictate what a rocky shoreline looks like.

By eating lots of mussels that outcompete wimpy algae and anemones for space, the sea star allows a lot of different species to stick around. In other words, the sea star maintains species diversity of this community by preventing the mussel bullies from taking over the schoolyard. That’s one simple, but powerful concept….one species can be the keystone for maintaining a system. Lose that species, and you lose the system.

Ok, let’s grab our ecological concept and travel back in time to Dr. Paine’s earlier research at Bay Mouth Bar. Wow, the precursor to the keystone species concept may be slithering around our backyard of Bay Mouth Bar in the form of the majestic horse conch! In this earlier work, the arrival of this big boy at the bar was followed by the disappearance of all of the former big boys (like this lightning whelk). By eating lots of these potential bullies, the horse conch may be the key for keeping this system so diverse in terms of other wimpy snails.

But why should anyone other than an ecologist care about the keystone species concept and its ability to link Bay Mouth Bar with rocky shorelines of the Pacific NW? Well, what if the lightning whelks eat a lot more clams than do other snails, and less clams buried beneath sediments means less of the sediment modification that can really promote seagrass (Read more about the symbiotic relationship between bivalves and seagrasses here)? Thanks to Randall’s previous seagrass post, we can envision that less horse conchs could lead to less clams, less seagrass, and then finally a lot less of things that are pleasing to the eye (e.g., birding), to the fishing rod (e.g., red drum), to the stomach (e.g., blue crabs), and ultimately to our economy.

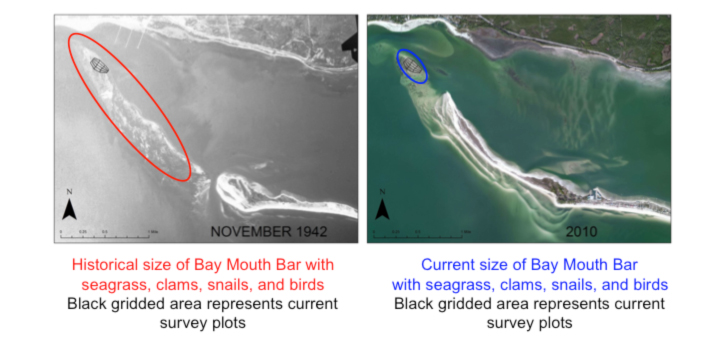

For the past two years, I’ve really enjoyed retracing Dr. Paine’s footsteps at Bay Mouth Bar. But lately, I’m feeling a little more urgent about needing to better understand this system because it’s disappearing (aerial images provided by USGS’s online database at http://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/).

To figure this out, we repeat a lot of what Dr. Paine did five decades ago. At the same time, we are testing some new ideas about how this system operates. For example, if the horse conch is the keystone species, is it dictating what Bay Mouth Bar looks like by eating stuff or by scaring the bully snails? How exactly does or doesn’t the answer affect clams, seagrasses, birds and fishes?

Luckily, because this system is so close, with some persistence and some good help, we’ll soon have good answers to those questions.

Cheers,

David

Ps: Many thanks to Mary Balthrop for helping us access this awesome study system every month.

In the Grass, On the Reef is funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

1 comment

[…] […]

Comments are closed.