Episode 6: Seagrass Beds | Blue Carbon Where the Stingray Meets the Horse Conch

At the beginning of September, Randall and David had a visit from Dr. Peter Macreadie of the University of Technology, Sydney. In this video, Randall takes Dr. Macreadie for a snorkel in St. Joseph Bay.

Dr. Randall Hughes FSU Coastal & Marine Lab

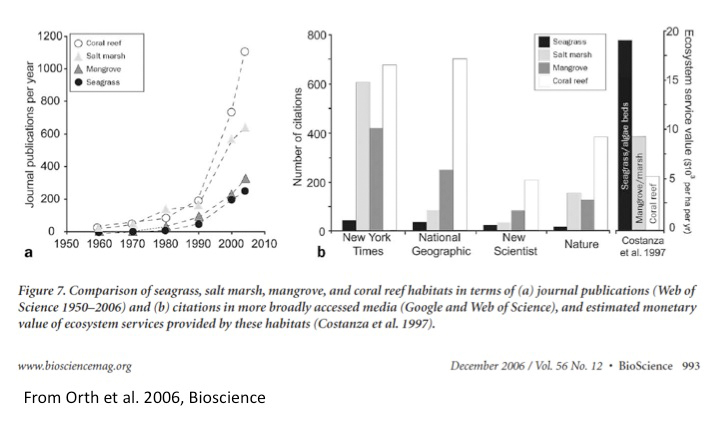

We now focus our attention to seagrasses, which as it turns out, often don’t get a lot of attention, at least in comparison to other marine habitats like coral reefs or even salt marshes.

Randall snorkels in a seagrass bed in Saint Joseph Bay Peninsula State Park. Photo by Dr. Peter Macreadie. Peter is a researcher from the University of Technology, Sydney, who is visiting Randall and David.

In part, this lack of attention is due to the fact that seagrasses typically live completely underwater, except at very low tide, and so they are not as noticeable as marshes are. In addition, seagrasses often occur in shallow estuaries not known for their great visibility (and thus not as ideal a location as coral reefs for snorkelers or scuba divers). And, although I disagree, some people just don’t find them very pretty.

Last week as I was starting to think about this post, there was a small uptick in the number of media articles related to seagrasses, at least in Australia. The increased interest was in response to a proposal by the Environment Minister, Tony Burke, to require greater seagrass protection from mining and development projects (read more in this article from the Brisbane Times). As justification for the increased financial burden on companies, Mr. Burke cited the many benefits that seagrasses provide. And just what are those?

Seagrasses (like salt marshes and oyster reefs) provide habitat for many, many fishes and invertebrates. Studies have found that the number of animals living in seagrasses beds can be an order of magnitude higher than the number living in adjacent coastal habitats. Many of these animals rely on the seagrass beds as a “nursery” that protects them from predators until they grow larger. And lots are recreationally and commercially important species that we like to eat. (Scallops, anyone?)

Seagrasses (like salt marshes and oyster reefs) provide habitat for many, many fishes and invertebrates. Studies have found that the number of animals living in seagrasses beds can be an order of magnitude higher than the number living in adjacent coastal habitats. Many of these animals rely on the seagrass beds as a “nursery” that protects them from predators until they grow larger. And lots are recreationally and commercially important species that we like to eat. (Scallops, anyone?)

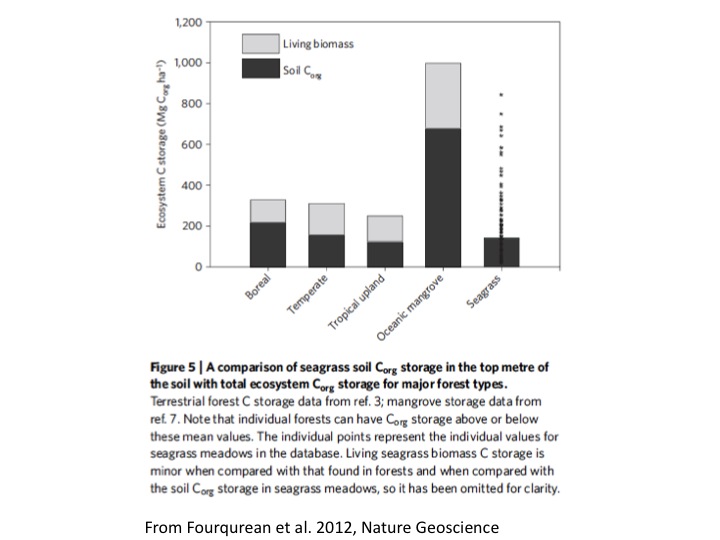

Seagrasses are also incredibly productive plants, sometimes growing more than 1cm per day, and rivaling our most productive crop species like corn. Because a significant portion of this plant material (particularly the roots and rhizomes below ground) stays in place once the plants die, seagrasses can also serve as important ‘carbon sinks’, or buried reservoirs of carbon. In fact, a recent study estimates that the carbon stored in the sediments of seagrass beds is on par with that stored in the sediments of forests on land!

Although lots of the productivity of seagrass beds makes its way underground, some of it does get eaten. Major consumers of seagrasses include urchins and fishes, as well as the more charismatic dugongs, manatees, and sea turtles.

Seagrasses (like salt marshes) also play an important role in reducing nutrients that run off from land into the water. Unfortunately, these nutrients can also lead to the loss of seagrasses, by promoting increased growth of algal “epiphytes” that grow on the blades of the seagrasses themselves. When there are not enough small fishes and invertebrates around to eat these algae, they can overgrow and outcompete the seagrass, leading to its decline. And when the seagrasses become less abundant, the animals that rely on them are also often in danger.

Seagrasses (like salt marshes) also play an important role in reducing nutrients that run off from land into the water. Unfortunately, these nutrients can also lead to the loss of seagrasses, by promoting increased growth of algal “epiphytes” that grow on the blades of the seagrasses themselves. When there are not enough small fishes and invertebrates around to eat these algae, they can overgrow and outcompete the seagrass, leading to its decline. And when the seagrasses become less abundant, the animals that rely on them are also often in danger.

The Big Bend and Panhandle of Florida are home to expansive seagrass beds that also often go unnoticed. But they contribute to the productivity, diversity, and beauty of this area in many ways, as anyone who has been scalloping recently has surely realized!

Here is a quick guide to the animals featured in the video above:

0:40 Horse conch and sea urchin joined suddenly by a stingray

1:41 Juvenile pinfish

1:18 Two shots of a bay scallop

1:33 Sea urchin

1:49 Pen shell clam covered in sea stars (2 shots)

1:56 Horse conch

In the Grass, On the Reef is funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

1 comment

[…] HomeActivitiesPaddlingHikingBird/ Wildlife WatchingArt/ PhotographyHistory/ Archeology ← What Have Seagrasses Done For Me Lately? 107 Miles to Go* […]

Comments are closed.