Dr. David Kimbro FSU Coastal & Marine Lab

Unlike most of the experiments that I’ve conducted up to this point in my career, the oyster experiment from this past summer does not contain a lot of data that can be analyzed quickly.

Unlike most of the experiments that I’ve conducted up to this point in my career, the oyster experiment from this past summer does not contain a lot of data that can be analyzed quickly.

For example, predator effects on the survivorship of oysters can be quickly determined by simply counting the number of living as well as dead oysters and then by analyzing how survivorship changes across our 3 experimental treatments (i.e., cages with oysters only; cages with mudcrabs and oysters; cages with predators, mudcrabs, and oysters). But this simple type of data tells us an incomplete story, because we are also interested in whether predators affected oyster filtration behavior and whether these behavioral effects led to differences in oyster traits (e.g., muscle mass) and ultimately the oyster’s influence on sediment characteristics. If you recall, oyster filter-feeding and waste excretion can sometimes create sediment conditions that promote the removal of excess nitrogen from the system (i.e., denitrification)

As we are currently learning, getting the latter type of data after the experiment involves multiple time-consuming and tedious steps such as measuring the length and weight of each oyster, shucking it, scooping out and weighing the muscle tissue, drying the muscle tissue for 48 hours, and re-weighing the muscle tissue (read more about this process here).

After repeating all of these steps for nearly 4,000 individual oysters, we can subtract the wet and dry tissue masses to assess whether oysters were generally:

(a) all shell…“Yikes! Lot’s of predators around so I’ll devote all of my energy into thickening my shell”

(b) all meat…“Smells relaxing here, so why bother thickening my shell”

(c) or a mix of the two.

For the next two months, I will resemble a kid with a full Halloween bag of candy who cannot wait to look inside his bag to see whether it’s full of tricks (nonsensical data) or some tasty treats (nice clean and interesting data patterns)! I’ll happily share the answer with you as soon as we get all the data in order.

Because of this delay, let’s explore some new research of mine that examined how predators affect prey traits in local marshes and why it matters.

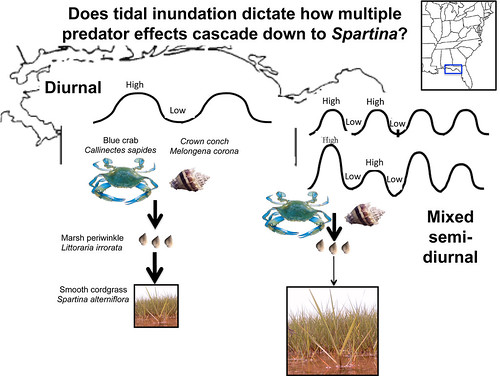

There are two main ingredients to this story:

(a) tides (high versus low) dictate how often and how long predators like blue crabs visit marshes to feast on tasty prey.

(b) prey are not hapless victims; like you and me, they will avoid risky situations.

In Spartina alterniflora systems, periwinkle snails (prey) munch on dead plant material (detritus) lying on the ground or fungus growing on the Spartina leaves that hover over the ground. Actually, according to Dr. B. Silliman at the University of Florida, these snails farm fungus by slicing open the Spartina leaves, which are then colonized by a fungal infection. If snails fungal farm too much, then the plant will eventually become stressed and die.

In Spartina alterniflora systems, periwinkle snails (prey) munch on dead plant material (detritus) lying on the ground or fungus growing on the Spartina leaves that hover over the ground. Actually, according to Dr. B. Silliman at the University of Florida, these snails farm fungus by slicing open the Spartina leaves, which are then colonized by a fungal infection. If snails fungal farm too much, then the plant will eventually become stressed and die.

So, I wondered if the fear of predators might control the intensity of this fungal farming and plant damage.

For instance, when the tide floods the marsh, snails race (pretty darn fast for a snail!) up plants to avoid the influx of hungry predators such as the blue crab.

After thinking about this image for a while, I wondered whether water full of predator cues might enhance fungal farming by causing the snail to remain away from the risky ground even during low tide. Eventually, the snail would get hungry and need to eat, right? Hence, my hypothesis about enhanced fungal farming due to predator cues. I also wondered how much of this dynamic might depend on the schedule of the tide.

After thinking about this image for a while, I wondered whether water full of predator cues might enhance fungal farming by causing the snail to remain away from the risky ground even during low tide. Eventually, the snail would get hungry and need to eat, right? Hence, my hypothesis about enhanced fungal farming due to predator cues. I also wondered how much of this dynamic might depend on the schedule of the tide.

Before delving into how I answered these questions, you are probably wondering whether this nuance really matters in such a complicated world. Fair enough, and so did I.

Addressing this doubt, I looked all around our coastline for any confirmatory signs and found that Spartina was less productive and had a lot more snail-farming scars along shorelines subjected to a diurnal tidal schedule (12 hours flood and 12 hours ebb each day) when compared to shorelines subjected to a mixed semidiurnal schedule (2 low tides interspersed among 2 high tides that are each 6 hours). Even cooler, this pattern occurred despite there being equal numbers of snails and predators along both shorelines; obviously density or consumption effects are not driving this pattern.

Ok, with this observation, I felt more confident in carrying out a pretty crazy laboratory experiment to see if my hypothesis might provide an explanation.

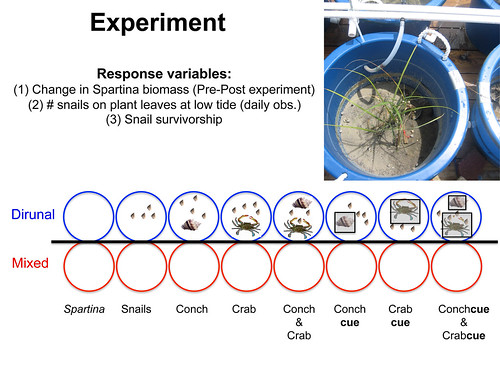

Enter Bobby Henderson. This skilled wizard constructed a system that allowed me to manipulate tides within tanks and therefore mimic natural marsh systems; well, at least more so than does a system of buckets that ignore the tides.

Within each row of tide (blue or red), I randomly assigned each tank a particular predator treatment. These treatments allowed me to dictate not only whether predators were present but whether they could consume & frighten snails versus just frightening them:

-Spartina only

-Spartina and snails

-Spartina, snails, and crown conch (predator)

-Spartina, snails, blue crab (predator)

-Spartina, snails, crown conch and blue crab (multiple predators)

-Spartina, snails, cue of crown conch (non-lethal predator)

-Spartina, snails, cue of blue crab (non-lethal predator)

-Spartina, snails, cues of crown conch and blue crab (non-lethal multiple predators)

After a few weeks, I found out the following:

After a few weeks, I found out the following:

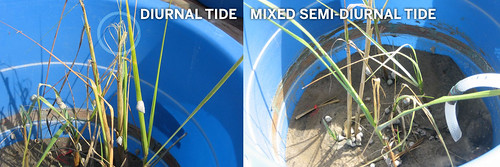

(1) Predators caused snails to ascend Spartina regardless of tide and predator identity. In other words, any predator cue and tide did the job in terms of scaring the dickens out of snails.

(2) Regardless of tide, blue crabs ate a lot more snails than did the slow moving crown conch and together they ate even more. This ain’t rocket science!

(3) In this refuge from the predators, snails in the diurnal tide wacked away at the marsh while snails in the mixed tide had no effect on the marsh.

Whoa…the tidal schedule totally dictated whether predator cues indirectly benefitted or harmed Spartina through their direct effects on snail predator-avoidance and farming behavior. And, this matches the observations in nature… pretty cool story about how the same assemblage of predator and prey can dance to a different tune when put in a slightly different environment. This study will soon be published in the journal Ecology. But until its publication, you can check out a more formal summary of this study here.

If this sort of thing happens just along a relatively small portion of our coastline, I can’t wait to see what comes of our data from the oyster experiment, which was conducted over 1,000 km.

Till next time,

David

1 comment

[…] […]

Comments are closed.