Dr. Randall Hughes FSU Coastal & Marine Lab

The answer to this seemingly rhetorical question was the subject of a recent review by Edward Barbier and colleagues in the journal Ecological Monographs. They focused not only on salt marshes, but also coral reefs, seagrass beds, mangroves, and sand beaches / dunes. The impetus for the analysis was the recognition that many coastal habitats are in decline – for instance, 50% of salt marshes are lost or degraded around the world – and the belief that we need a better understanding of the true costs of these losses.

The answer to this seemingly rhetorical question was the subject of a recent review by Edward Barbier and colleagues in the journal Ecological Monographs. They focused not only on salt marshes, but also coral reefs, seagrass beds, mangroves, and sand beaches / dunes. The impetus for the analysis was the recognition that many coastal habitats are in decline – for instance, 50% of salt marshes are lost or degraded around the world – and the belief that we need a better understanding of the true costs of these losses.

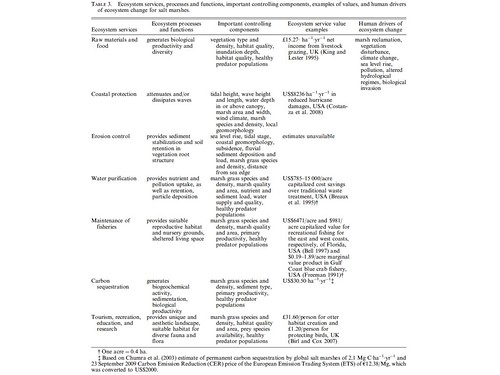

So, how do you go about putting a value on a salt marsh, or any other habitat? First, you identify the “ecosystem services” that the habitat provides. As defined by the US Environmental Protection Agency, ecosystem services are the “direct and indirect contributions that ecosystems make to the well-being of human populations”. As we’ve discussed in earlier posts, these services include recreational activities (birding, kayaking), raw materials (wood from mangroves), erosion control, water filtration, and provision of fisheries / nursery habitat, among others.

Next, you determine the monetary value of these services. For some services, such as raw materials traded on open markets, this is a relatively straightforward task. For those services that are not marketed, however, it becomes more challenging. Important considerations include identifying the key features of the habitat that are responsible for providing the service and determining how variation in these features changes the magnitude of the service. For example, the value of salt marsh habitat for foraging birds can depend on the density of the plant stems (very dense beds can reduce bird foraging), which is in turn influenced by the particular marsh plant species present. In short, not all marshes are created equal – the specifics of a given location and the particular physical and biological conditions surrounding it will influence the value of ecosystem services provided by that habitat.

Because a one-size-fits-all approach to valuing ecosystem services is problematic, Barbier and colleagues did not attempt to convert values from the studies they identified into a common currency or a common area. Nor did they sum the values for different salt marsh services to come up with one single value – in fact, values for some key marsh ecosystem services such as erosion control don’t even exist! Despite the unknowns, there are several good estimates for the fisheries value of salt marshes in the Gulf of Mexico, based on earlier studies by Zimmerman in 2000 and Bell in 1997 (see the table below, excerpted from Barbier et al. 2011).

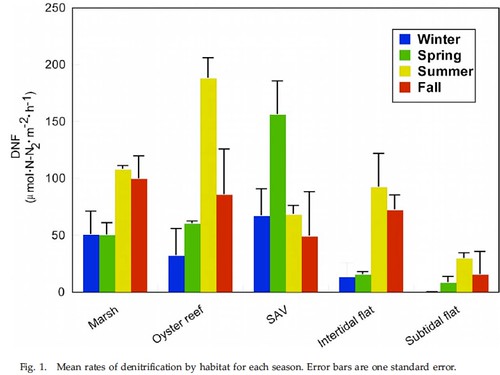

Curiously, Barbier and colleagues did not address the value of oyster reefs, despite the fact that they too provide many of the same ecosystem services as the coastal habitats included in the study. Estimates of some of these services do exist: for instance, Piehler and Smyth quantified the rate of denitrification (removal of biologically available nitrogen) for several coastal habitats, including salt marshes and oyster reefs.

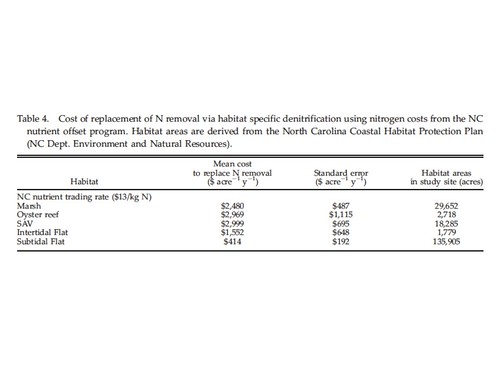

Then, using rates from the North Carolina nutrient offset program, they calculated the mean monetary cost to replace the nitrogen removal services provided by each of these habitats. Oysters and salt marsh (along with seagrasses) were the most “valuable” in terms of nitrogen removal: an acre of oyster reef is worth $2969 per year, compared to $2480 per year for an acre of salt marsh.

In a separate study, Grabowski and Peterson found that the value of oysters as a fished commodity (i.e., if you were going to eat them at a raw bar) was ~40% less than the value of those same oysters left intact as habitat for fish species. Further, they estimated that a 1-acre oyster reef that lasted for 50 years would generate $40,000 in increased commercial finfish and crab fisheries.

In their review, Barbier and colleagues point to a number of gaps in our current understanding of the value of these coastal habitats. For one, we need ecological data on some of the key services that have yet to be valuated (e.g., erosion control in salt marshes) to provide the basis for the valuation process. In addition, we need to consider how coastal habitats that often occur in close proximity act in concert to provide common ecosystem services. Because despite the limitations and challenges of the valuation process, the need to justify the conservation and restoration of coastal habitats in concrete terms ($$) that can be equated with competing interests is not likely to wane anytime soon.

In their review, Barbier and colleagues point to a number of gaps in our current understanding of the value of these coastal habitats. For one, we need ecological data on some of the key services that have yet to be valuated (e.g., erosion control in salt marshes) to provide the basis for the valuation process. In addition, we need to consider how coastal habitats that often occur in close proximity act in concert to provide common ecosystem services. Because despite the limitations and challenges of the valuation process, the need to justify the conservation and restoration of coastal habitats in concrete terms ($$) that can be equated with competing interests is not likely to wane anytime soon.

2 comments

[…] strange to think that these little critters have such an impact on us (Read a post by Dr. Randall Hughes on the financial value of coastal ecosystems). They affect the food we eat, the economy of the coast. They affect the physical coast itself, […]

[…] of marshes are described in greater detail in a recent review by Barbier and colleagues (which I referenced on this blog in May of 2011). Here is the table that they put together summarizing the monetary benefits that we […]

Comments are closed.