We dive into the Wacissa River with a team of scuba-diving archeologists. What did they find? And what do their findings mean within the larger picture of prehistoric Florida? Read on. Big thanks to David Ward and Robert Daniels of the Aucilla River Group for helping us arrange the shoot and transporting the crew to the site. And thanks to Hot Tamale, whose music is featured in the video.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

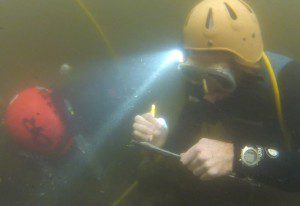

Some time ago, possibly about 12,000 years or so, a group of hunters stopped by the Wacissa River and made some tools. They’re not likely to have self-identified as members of the Suwannee culture group, though that’s how archeologists classify them based on the way they crafted their spear points. These paleolithic humans left a mess of bone and rock on what may or may not have been a riverbank at the time. That refuse is of interest to Morgan Smith, a PhD. student at Texas A & M University.

This past June, Morgan led an excavation of a small section of Wacissa riverbank. His is one of several known sites in the Aucilla/ Wacissa watershed that span several thousand years of Florida panhandle prehistory. At his site, Morgan found a handful of larger tools or spear tips, and exponentially more bits of bone and chert that flaked off when the tools were being made. Each little bit was meticulously cataloged. When it comes to understanding the original settlement of Florida, and of the New World, each archeological site is like a chert flake, a piece of a larger puzzle that becomes more and more complete with every excavation. In Jefferson County, where these sites reside, that prehistory is a big deal.

This past June, Morgan led an excavation of a small section of Wacissa riverbank. His is one of several known sites in the Aucilla/ Wacissa watershed that span several thousand years of Florida panhandle prehistory. At his site, Morgan found a handful of larger tools or spear tips, and exponentially more bits of bone and chert that flaked off when the tools were being made. Each little bit was meticulously cataloged. When it comes to understanding the original settlement of Florida, and of the New World, each archeological site is like a chert flake, a piece of a larger puzzle that becomes more and more complete with every excavation. In Jefferson County, where these sites reside, that prehistory is a big deal.

Earlier this month, Monticello hosted the First Floridians | First Americans Conference. Morgan and Dr. Jessi Halligan, who we see helping Morgan in the video above, both spoke at the conference. Morgan’s faculty advisor, and Dr. Halligan’s former advisor, Dr. Michael Waters, gave a keynote presentation on genetic evidence for the identity of the first Americans. The question and answer period after Dr. Waters’ presentation showed that local residents were engaged in the topic, with a fair amount of discussion focused on something called the Solutrean hypothesis (more on that later).

When Morgan displayed his finds for researchers a month after his excavation, he encountered a similar excitement regarding the artifacts and their potential place in the succession of indigenous American cultures. With some pretty old archeological sites located so far from where we believe people had crossed into the Americas, this region is an intriguing part of the big picture. It has a potential to cause us to rethink our theories about the first Americans, and there’s a potential for headline grabbing discoveries to be made by researchers working here. Before we lift the veil on early American settlement, however, rigorous scientific work has to be done.

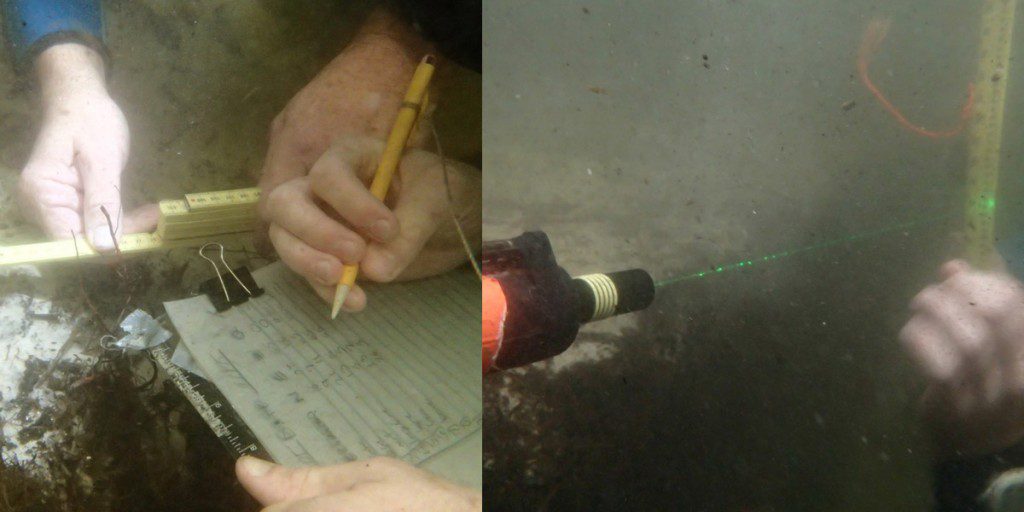

Writing on mylar paper, Morgan and his colleagues note the exact location of every artifact found. To ensure that sediment was excavated evenly, the team used a laser level. Photos courtesy Ryan Means.

In the Lab | Doing the Little Things

Our video focuses on the fun-looking part of this research: teams of scuba divers, working from a ramshackle camp beside a canopied river, dug for artifacts. They bagged the larger items, and used a floating dredge to vacuum up sediment and filter it through three screens to collect the small bits. They worked and ate under a makeshift tarp tent, and their dogs lied in whatever spot would get them the least muddy. That’s the visually compelling part of this story. But those little bits of bone and chert have their own, much larger story to tell. That story gets written in the lab.

Here’s a look at the process:

- For any of the high-tech lab procedures to be able to tell Morgan anything, each artifact needs to have had information collected about it on site. You see this in the video. They slowly worked their way from the top of the riverbank, removing chunks of sediment ten centimeters at a time. When they started finding artifacts, they slowed down even more and did five cm increments. Every item dug out from the bank had a sheet attached to it with its exact location in three dimensional space- x, y, and z axis. They weren’t able to be as specific with smallest pieces dredged from the bank, but they logged them within 5 cm of where they were dredged.

- The larger pieces can tell us something even before they head to the lab. As Morgan

tells us in the video, one of these is a Suwannee base. Looking at it from above, you can extrapolate the spear tip shape, broken off midway. The shape of the base was enough to see that it was made in a similar fashion to other known Suwannee points.

- But what of those smaller bits and pieces? This is where we can learn a lot more about the lifestyle of these mysterious Suwannee people. Morgan and his team have recently started sorting their 1/16th inch samples; that is, the artifacts filtered through their smallest mesh screen. Morgan explained to me why they’re using such a small mesh. “While using a smaller screen exponentially increases the workload in the lab (it easily triples processing time), you can only excavate a site once and what you miss you can’t factor in.” So what have they found to make the extra work worth it?

- One thing they found were small animal bones. This means “the people also exploited smaller animals that were likely trapped, not hunted.” They also found fish bones as well. The extra screen allowed the research team to learn more about the overall diet of the Suwannee, from which we can infer a wider range of activity; in addition to being the big game hunters we knew them to be, they were trappers and fishers as well.

- They also found a lot of tiny chert flakes. But why would this be important? According to Morgan, “the presence of many tiny flakes indicates that people were constantly using and re-sharpening their tools, which generally only occurs at areas inhabited for longer periods.” So this may have been more than a temporary encampment.

- A smaller mesh would allow them to find smaller implements, like needles and bone pins. He has what may turn out to be a bead, which is relatively rare for a site of this age.

-

Some of the small bones might offer a clue as to the environment. We don’t know for sure whether the Wacissa flowed there 12,000 years ago, but the research team did find muskrat elements in their 1/16th screen. “These are wetland adapted creatures that occupy a specific niche in the environment. If we assume they occupied the same niche in the past and that they were not brought to the site from far away, we can easily say that there was a substantial wetland or water source nearby.”

- All of the small artifacts found using the smaller screen are important for another reason: “the presence of such small material supports the fact that the site is intact and hasn’t been disturbed. Had this material been deposited or reworked by a flood, you would not expect such small items (which could easily be swept away in steady water) to be laying next to large tools that would take strong flood events to be moved.”

They’re using a few different methods to date their finds. Two items were recently sent off for radio-carbon dating; they should have that information shortly. They will be using two different methods to test the soil around the artifacts as well. Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) will determine the last time the sands by each item were exposed to sunlight. This gives them the latest possible dates for each item, before they became buried. Micromorphology looks at how “individual sediment particles interact, allowing us to see what kinds of processes may have affected the artifacts (storms, floods, fires, etc). This is important to understanding how intact the deposit truly is, and whether or not it may be contaminated.”

These techniques are pricey (between $600-700 for OSL and $120 for micromorphology). Morgan is writing a grant to cover the costs.

But is it Pre-Clovis?

When Morgan gets his dating information back, it may confirm the dates associated with Suwannee- about 13,000-12,000 years before present. Or, could it be older?

In the video, you see a little bit of a gathering held at the Florida Geological Survey. Among of the collected group of researchers were the discoverers of the site, geologist Harley Means and biologist Ryan Means. Also present was former state archeologist Dr. James Dunbar. Morgan presented his finds, and there was a lively discussion about the items found and, in particular, the age of the site.

At some point in the conversation, Harley became animated when talking about the lack of hard dates for paleo-indian sites in Florida. “What we do not have any idea on is- what are Suwannees? What are Simpsons? What are Page-Ladson lancelets?” Suwannee and Simpson are cultural groups represented along the Wacissa and Aucilla Rivers (and in the southeast), and Page-Ladson is an archeological site on the Aucilla that is one of the oldest in the country (recently carbon dated to 14,400 ybp). What he wanted to know, the question he most wanted answered- are any of them pre-Clovis?

In regards to his own site, Morgan didn’t think so. The reason why? The number of points they found. “To me, it would be odd that we would have such a high concentration, when we’re kind of scraping bottom for pre-Clovis elsewhere.”

Clovis is a culture from about 13,200 to 12,900 years ago. Characterized by their Clovis points, evidence of Clovis culture has been found across North America. They’re believed to be the ancestors of most, if not all, modern native groups. And, it’s a culture believed to be entirely unique to North America, not a continuation of cultures carried across the Bering Straits. Archeological sites older than 13,200 ybp are considered pre-Clovis. Pre-Clovis cultures in Florida, such as Page-Ladson, muddy up the timeline of human settlement in the Americas.

One solution to that particular problem is a cross-Atlantic crossing by Europeans- the Solutrean hypothesis. One of its chief proponents was a keynote speaker at the First Floridians Conference, Dr. Dennis Stanford of the Smithsonian Institute. Solutrean culture was common in France and Iberia, and had points similar to Clovis. Solutrean points disappeared in Europe almost two-thousand years before Clovis points appeared in the United States. Might there be a connection between the two?

Dr, Michael Waters, Texas A & M University. Michael is Morgan Smith’s advisor, and Jessi Halligan’s former advisor. Dr. Waters and his protege’s have been active in excavating the Aucilla and Wacissa Rivers. “The Aucilla is a gem,” he told an audience at the First Floridians Conference in Monticello.

According to the conference’s other keynote speaker, Dr. Michael Waters, genome mapping of the only found human associated with Clovis culture discredits the Solutrean hypothesis. That individual is known as Anzick-1, a male infant found at a Montana site. That individual is descended from Siberian ancestors and is closely related to all modern native American groups. Other early skeletons have also been analyzed and found to have been of Asian origin.

Does that mean that there couldn’t have been small European populations that whose genetic lineage died off long ago? And, while we’re at it, could Morgan’s site be pre-Clovis? Anything is possible, and any newly discovered paleo-site could cause us to further rethink what we know about the First Americans. In the meantime, Morgan and other archeologists like him have work to do, examining small pieces of bone and chert, and raising money to test their samples.

Is Archeology Equitable?

We shot this video in June, but I knew it wouldn’t air until September at the earliest (and here we are with October winding down). I was excited about this story, however, so I wrote a blog post about it. Looking at the positive response when I shared the post on the WFSU Facebook page, I was pleased. Within a day, though, I was blindsided by a slew of comments on the blog post. Most of those were negatively directed at an individual, some were more generally upset about Florida artifacts being taken away to Texas. What I started taking away from the comments was a general distaste for the laws governing artifacts found in Florida. I contacted a couple of the commenters- Teben Pyles and his father Thornton. Teben is the president of the Tri-State Archeological Society. I interviewed them about the place of amateurs in Archeology; watch for that in a couple of weeks. We talk about the potential for increased citizen science (amateurs and PhD’s working together), and where some restrictions could be loosened. Enough people seemed passionately opposed to the current system, and so I felt it was important to present their viewpoint.

Raising Naturalists

Ryan Means holds a paleo tool at a site he discovered with his brother on the Wacissa River. Photo Courtesy Ryan Means.

There’s one more tidbit that I wanted to share from the video above. Also present at the Florida Geological Survey meeting was Ryan and Harley’s father, Dr. Bruce Means. Dr. Means is the president of the Coastal Plains Institute, and a former director of Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy. At one point in the conversation, he mentioned taking Ryan and Harley to the Wacissa as kids, introducing them to the place where they’d one day make their discovery. Being interested as I am in raising kids with nature, I couldn’t resist asking the patriarch of such a well-known family of scientists a little more about these experiences with his kids.

He spoke of diving the Wacissa in the 1970s when conducting research, and bringing the kids along. “By the time Harley was at least six, maybe it was five, I had him on a boat while I was diving” Means recalled, “… and he’s got a famous recollection where I found a Kirk serrated point and I put it in my mask. As I came up- he’s looking over waiting for me to come up, and he gets to see that thing right in the mask. That kind of fired him into [be]coming a geologist, paleontologist, naturalist. Neither of my sons has ever formally become a paleontologist, archeologist, but they certainly are interested in it. Harley’s a geologist, Ryan is a conservation biologist. That means we’re naturalists. We like all aspects of nature.”

Next week on Local Routes, and the WFSU Ecology Blog, I take my four-year-old son Max out on the Apalachicola River for two days of kayaking and camping on RiverTrek. Hearing the impact it had on Dr. Means’ sons to get them out in nature was heartening to me. I don’t expect Max and his brother Xavi to become professional naturalists like Ryan and Harley, but I do think regularly engaging them in outdoor activities will pay off in a positive way.

Come adventure with us in the Red Hills, Apalachicola River and Bay, the Forgotten Coast, and more! Subscribe to the WFSU Ecology Blog by Email.

To prepare for RiverTrek, Max and I participated in a warm up paddle on the upper Apalachicola. On our lunch break, Max wallowed in the mud on Means Creek, named for Dr. Bruce Means.