Hanna Garland FSU Coastal & Marine Lab

One of the most fascinating aspects of the field of science is the unpredictable patterns and directions that certain communities can take over a period of time. Whether the change in a habitat occurs due a spontaneous event such as a devastating hurricane or a longer, more gradual event such as climate change; it is important to understand the impacts these changes may have on the resident organisms as well as the future of the community. Studying how organisms respond to each other and their environment are key principles of ecology.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the field of science is the unpredictable patterns and directions that certain communities can take over a period of time. Whether the change in a habitat occurs due a spontaneous event such as a devastating hurricane or a longer, more gradual event such as climate change; it is important to understand the impacts these changes may have on the resident organisms as well as the future of the community. Studying how organisms respond to each other and their environment are key principles of ecology.

As David mentioned in the previous post, I have recently begun my graduate student work in St. Augustine, where I hope to gain a better understanding of the unique observations we have made while working in the area for the NSF oyster project.

As David mentioned in the previous post, I have recently begun my graduate student work in St. Augustine, where I hope to gain a better understanding of the unique observations we have made while working in the area for the NSF oyster project.

Other than being the nation’s oldest city, St. Augustine is a very dynamic place. From condominiums and restaurants to historic landmarks and beautiful beaches; the area is flooded with snow-birds during this time of year. More notably, St. Augustine has countless state parks, wildlife preserves, and protected habitats; which allow for not only attractions for tourists but areas of research for scientists and most importantly, shelter and nurseries for the resident wildlife.

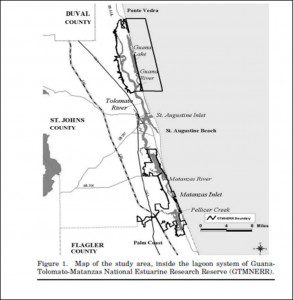

The Guana Tolomato Matanzas National Estuarine Research Reserve (yes, it is quite the mouthful, so we’ll refer to it as GTM NERR from now on) encompasses the majority of the salt marsh and mangrove tidal wetlands, oyster bars, estuarine lagoons, upland habitat and offshore seas surrounding the city of St. Augustine. For my project, I will be focusing on the southern component of the GTM NERR (the region south of St. Augustine). So…now what?

The Guana Tolomato Matanzas National Estuarine Research Reserve (yes, it is quite the mouthful, so we’ll refer to it as GTM NERR from now on) encompasses the majority of the salt marsh and mangrove tidal wetlands, oyster bars, estuarine lagoons, upland habitat and offshore seas surrounding the city of St. Augustine. For my project, I will be focusing on the southern component of the GTM NERR (the region south of St. Augustine). So…now what?

While conducting field work for the NSF oyster project, we began to notice an abnormal abundance of crown conchs at our St. Augustine site in comparison to the densities at the other three sites (almost four to five times greater). In tandem, the oysters were not very healthy and there was much higher mortality among these reefs. Now, you may ask, could this be due to the increased conch population or…some other factors?

After speaking with locals and other researchers at the University of Florida marine lab where we stay during NSF work, it appeared that the increased conch densities and oyster mortality was only found as far north as the Matanzas Inlet; in which, the conchs then became non-existent and the oysters were much healthier. However, these statements were merely observations and little scientific research had been done to support these claims. So here we go!

As I am sure Cristina can agree with her initial work on Baymouth Bar, surveying and dividing up a region becomes quite the undertaking; especially, in this case, when it stretches almost 14 miles long! However, after a week full of searching and “schmoozing” launch locations, non-stop loading and unloading the kayak from atop my car, paddling across the Matanzas River and inter-coastal waterway up into creeks and embayments and dragging my kayak across mud flats; I was able to have a solid feel of the oyster reefs in the area and was beginning to feel like a local.

More importantly, my surveys revealed that there truly was a spatial gradient of conch density and oyster health occurring throughout this region south of St. Augustine. The point at which the oyster communities change is around the Matanzas Inlet; which is one of the only two unimproved inlets remaining along the east coast of the United States.

More importantly, my surveys revealed that there truly was a spatial gradient of conch density and oyster health occurring throughout this region south of St. Augustine. The point at which the oyster communities change is around the Matanzas Inlet; which is one of the only two unimproved inlets remaining along the east coast of the United States.

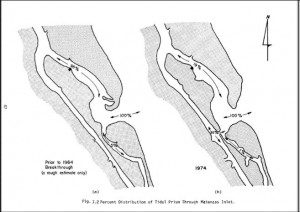

Coming full circle to the start of my post discussing factors that can trigger changes in community dynamics; the Matanzas Inlet is a prime example. Historically, the Matanzas Inlet provided access to the ocean solely from the Matanzas River; however, due to storms, the land separating the intercoastal waterway and the river broke, which allowed flushing of ocean water directly into the intercoastal waterway. This later caused sedimentation and the eventual drying up of the southern arm of the Matanzas River. This region presently looks like a sand dune lined with docks that once stood over water. This change in water flushing and flow dynamics as well as movement of marine organisms throughout the inlet greatly affects the habitats within the tidal estuaries; especially oyster reefs.

However, this is not the only possible cause for the crown conch density and oyster health gradient seen throughout this area. There are multiple biological and physical factors that could be acting individually and in combination with one another. A historically active clam lease in the river south of Matanzas Inlet has been hypothesized to have brought conchs to the area for food and since left them to prey on the oysters. Top-down effects such as the presence of a crown conch predator (i.e. larger gastropods like the Florida horse conch) in the region north could be controlling prey densities. Or simply the environmental conditions and tidal flushing patterns could be “just right” for conchs while being “all wrong” for oysters in the region south of the inlet. Now what are these specific “ideal” conditions? That is what I will hope to find out!

However, this is not the only possible cause for the crown conch density and oyster health gradient seen throughout this area. There are multiple biological and physical factors that could be acting individually and in combination with one another. A historically active clam lease in the river south of Matanzas Inlet has been hypothesized to have brought conchs to the area for food and since left them to prey on the oysters. Top-down effects such as the presence of a crown conch predator (i.e. larger gastropods like the Florida horse conch) in the region north could be controlling prey densities. Or simply the environmental conditions and tidal flushing patterns could be “just right” for conchs while being “all wrong” for oysters in the region south of the inlet. Now what are these specific “ideal” conditions? That is what I will hope to find out!

Through a series of biological (how many oysters are live/dead, how abundant are conchs, crabs, fish, etc. on the reef) and physical (water temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, pH, tidal inundation) surveys, field experiments, and hydrological and tidal flow mapping throughout this spring and summer; we will aim to gain a better understanding of the factors occurring individually as well as in tandem with one another that have created the complex ecological patterns among oyster reefs in this area.

I am eager to begin exploring these crown conchs at a deeper level, so stay tuned because despite all of our hypotheses and assumptions; we can never be sure of what else we could discover!

6 comments

Great explanation of all you’re doing in St. Augustine, Hanna. Keep us posted!!!

Sounds like very interesting work. Excellent job of explaining it to the non-scientists like myself.

Cool Hannie! Sounds like great work you are doing!!

Your research sounds way fun and I’m glad someone will be able to explain why we have changes in our gastropod populations and enviroment. I was wondering if crown conchs are tasty?? Maybe we could do our share to bring (oysters) & other things back in balance, although I guess the sedimentation is the problem. Keep up the good work -we appreciate your efforts on our behalf. Mary 🙂

Thank you Hanna for all your efforts (kayak on and off car roof) to do research for the health and balance of marine ecosystems. In hear the storms down there are intense and increasing in size and velocity so how all the little critters are doing is good to learn about. We here in Oregon are proud of your fine work. You GO girl! Babs, Maia and Howard

[…] fellow lab tech who is starting graduate school in the fall and who is looking into the abnormal levels of crown conchs on Randall and David’s Saint Augustine reefs. And we have also heard from Cristina Lima […]

Comments are closed.