The art and iconography of Muscogee shell carving is a window into Native cultures, their beliefs, and connection to nature. Thanks to Lynn Ivory for her photos of events at Fred George Basin Greenway and Park.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

Chris Thompson is practicing an ancient art form, but with a power tool. “Used to, you would carve with a stone, or another shell that was harder,” Chris says. “Those take a lot longer to carve with. That’s mainly why we use the Dremel.” Artistically, the speed of the Dremel’s engraving tip lets Chris carve deeper into the shell surface, so that modern shell carvings have greater relief than those made by Muscogee carvers of old.

Chris has arranged various shells on a table. We’re in the Museum at Fred George Basin Greenway and Park, where the Wildwood Preservation Society holds monthly lectures on Muscogee (also known as Creek) culture, local ecology, and archeology. The shells are an intersection of these subject matters, as you’ll soon see.

Chris Thompson carves grandmother weaver onto a gorget. He’s been carving for two years, after asking his mentor to teach him for four years. Why so long? “We do everything in fours,” Chris says.

The shells fall into two categories- disc shaped gorgets and large medicine cups. Gorgets are decorative pieces, cut from larger shells of different varieties. The medicine cups, however, are sacred, and are entirely made from large lightning whelk shells. Until recently, I wouldn’t have been able to to talk about medicine cups with a shell carver.

This has changed, due to the efforts of Daniel Penton, a ceremonial leader of the Florida Muscogee. As his daughter Misty tells us, “For about the last 20 years, he’s been trying to gently move us into- ‘We can’t keep all these things secret anymore.’ Because we’re losing the young people.”

This is Misty Penton’s mission with the Wildwood Preservation Society. Community members have come to the park to play the Muscogee ball game, watch Chris and his mentor, Dan Townsend, carve shells, and listen to Misty tell stories from Muscogee lore.

Her ambitions for the Greenway range from longleaf restoration to further explorations of archeological sites on the property. It all falls within the larger focus of sharing her Native culture, and its connection to nature. We can start to get a sense of this connection from Chris’s carvings.

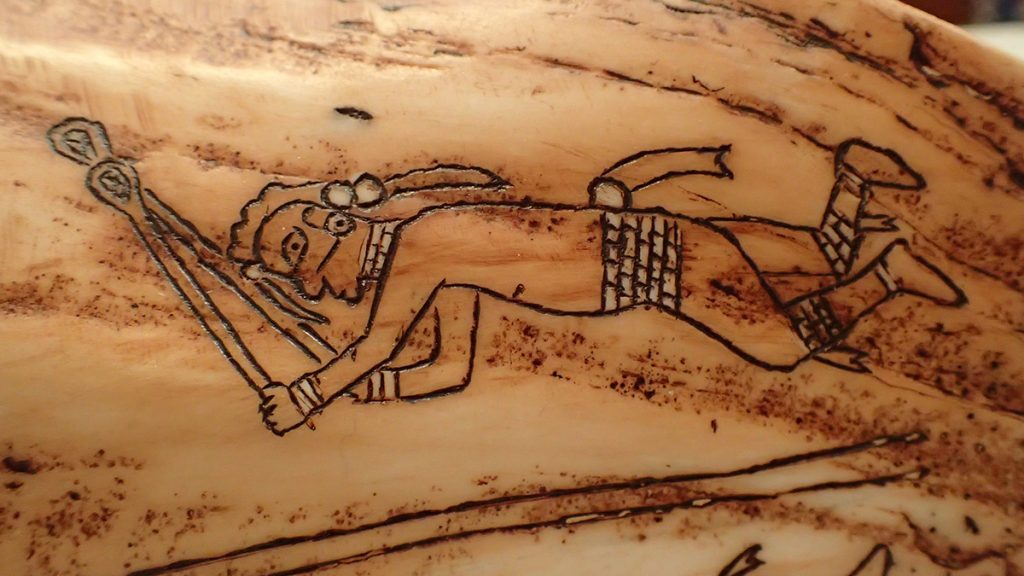

A lightning whelk engraved with a depiction of the Muscogee afterlife (See description in the next section), as interpreted by Chris Thompson.

For the Muscogee, Everything Goes to the Left

Let’s start with the medium itself. Lightning whelks are abundant on Florida’s Forgotten Coast. They are predators, hunting clams and mussels; in turn, they are hunted by tulip snails and the larger horse conch.

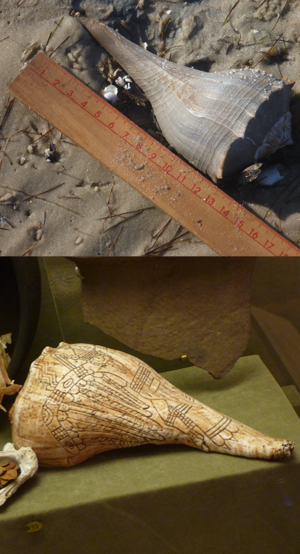

You often see their shells washed up on the coast; you can see them in action snorkeling over seagrass beds and open, sandy bottom. Specimens as large as the ones Chris uses to make medicine cups are rare; it takes decades of dodging shell hunters and predators to reach 15 or 17 inches in length.

Lightning whelks are remarkable for more than their size. The coast is filled with a huge diversity of snails. Of all those snails- crown conchs, moon snails, periwinkles, or even other whelks, such as the pear whelk- the lightning whelk is the only one with a shell that spirals to the left.

To the Muscogee, this is important.

Left- the Lightning whelk, Busycon contrarium. On the right is the Atlantic moon snail, Polinices duplicatus. The lightning whelk is the only snail whose shell spirals to the left.

“We dance to the left,” Chris says. “I do carvings to the left. The reason we do that type of thing is, we think it helps keep this middle world in balance.”

That’s why, traditionally, medicine cups have only been carved from lightning whelk shells. It’s a tradition that was starting to fall by the wayside.

“A lot of people, they don’t use medicine cups like these anymore,” Chris says. “They actually use regular shells, or little tin cups. And I started wanting to bring that back.”

In reviving this tradition, he’s preserving his heritage in two ways. Ceremonial leaders can use medicine cups like those used by generations past. Also, the artwork on the cups records Muscogee legends and lore, giving us a glimpse into their world view.

Grandmother Weaver and the Muscogee Ball Game

The first cup we see in the video is a work in progress. It shows Grandmother Weaver, a figure found in many Native American mythologies. In Muscogee lore, she takes the embers of a sycamore tree struck by lightning, and brings it across the water to give humans fire.

He’s carving the same image into a gorget in the video above, featuring the same solar cross on the spider’s thorax. To the medicine cup he will eventually add a representation of the lower, middle, and upper worlds.

Here we see a coming together of the middle and lower worlds. The deer represents the world we inhabit, the middle, while the fish represents the world “beneath the surface.” This is a world of chaos, the water upon which our world floats. The upper world is one of perfection and celestial bodies; Muscogee rules and rituals are intended to keep a balance between the upper and lower.

In the other medicine cup we see, we start heading into that upper world. People play the ball game to honor the creator. When they die, their souls go up the ball pole and into the Milky Way to be with their ancestors (depicted in the banner image of this post).

As Misty explained to me, the Milky Way is a part of the upper world, kind of at its entrance, where it connects to ours. The stars are the campfires of our ancestors, which we find with the help of our dogs.

In this gorget, Chris has carved a butterfly. As Misty explains, butterflies serve a dual role as pollinators, and as carriers of human souls. In the Muscogee world, many plants and animals have a similar second significance. Foxes represent family, and taking care of your loved ones. Sweet gum trees are sacred, and carry the burdens of the community.

Digging Deeper in Time: Mississippians and Beyond

If you have time one day, you can indulge in a little bit of Google anthropology. Search for “grandmother weaver.” You’ll find a variety of stories from different Native cultures across North America. The Hopi (Southwest) believe she created humans. To the Ojibwe (south Canada/ north U.S.), she is a helper of humans; Ojibwe women weave spider web charms to protect loved ones.

Some of the stories are similar to the Muscogee’s. I showed my son a photo of the grandmother weaver medicine cup, and he surprised me by saying he knew about her. “She brought the sun to humans,” Max said. “We learned about her in kindergarten.”

Misty, an archeologist by trade, tells me that evidence points to this shared lore originating as far away as Mesoamerica. This region was home to the Olmecs, Maya, and Aztec cultures. It’s also where corn was developed several thousands of years ago, likely from a grain called teosinte. It’s not hard to imagine that, as corn spread through trade networks and made its way through North America, it brought legends and beliefs along with it.

In the iconography used in Muscogee shell carving, Chris Thompson sees evidence of a more recent civilization linked by trade. “These shell carvings go back to the Mississippian time period,” Chris says. “You can tell- from Choctaw, Cherokee, Alabama, Coushatta, Muscogee Creek- that, basically, at one point and time, we were all one people.”

Mississippian Culture covered the eastern United States starting about 800 AD, and is best known for the large earthen mounds they left behind. By the time Hernando de Soto searched the southeast for gold in 1539-40, the culture had mostly faded.

In fact, the Apalachee people de Soto encountered at Anhaica had only abandoned their mounds by Lake Jackson fifty years earlier. Located in modern day Myers Park in Tallahassee, Anhaica was the political center of a culture similar to that of the Muscogee.

Misty Penton, holding a pair of Muscogee ball game sticks. The Apalachee played their ball game with their hands.

Apalachee Ball Game and Medicine Cups

Years ago, I produced a segment on the Apalachee ball game for our Florida Footprints series. When the Apalachee were occupying Leon and Jefferson counties in Florida, the Muscogee were in Georgia and Alabama. The Seminoles, which many associate with our area, are a newer combination of several cultures, predominantly Muscogee.

Anyhow, it was hard not to notice a few similarities between the Apalachee and their neighbors to the north, starting with their ball games. There were differences- Muscogee top their pole with a fish, Apalachee with an eagle’s nest. But the goal was the same.

Different villages within each culture played each other to, as Misty puts it “work out aggressions.” The games could be violent, as you hear about in that Florida Footprints segment. But they were less violent than warfare.

“You might lose an eye, or break a leg,” Misty says. “But you don’t usually lose a person.” Known as the “Little Brother of War,” the ball game helped keep the peace between Muscogee villages.

Top-lightning whelk on a sand flat off of Alligator Point. Below, an Apalachee medicine cup carved from a lightning whelk shell.

And of course, both cultures had their medicine cups. In 2012, I wrote a blog post about the Apalachee’s use of lightning whelks in the black drink ceremony held the night before ball games. The black drink is a tea brewed from yaupon holly, Ilex vomitoria. That species name is telling; the black drink was a form of ritual purification through regurgitation.

Interviewing Mission San Luis archeologist Dr. Bonnie McEwan, I learned that our local lightning whelk shells were valued throughout the Mississippian trade network. “In general, ” Dr. McEwan said, “most of these items are found in association with burials of high status individuals throughout the Mississippian world since they conferred prestige.”

Archeologists have found whelks from Apalachee Bay as far away as Arkansas and Illinois.

A Little Bit of Marine Biology

In the thumbnail image for the video above, taken from an early section of the video, we see various snail shells taken from our photographic archive. Each has its role to play in our coastal ecosystems.

Let’s take a closer look at the snails in this frame, starting at the lower left, moving counter clockwise around the central image of a lightning whelk medicine cup.

Lower left- True tulip (Fasciolaria tulipa), on an Alligator Harbor oyster reef. Tulip snails are a top predator in local seagrass beds, eating a variety of snails, including the lighting whelk. They may also prey on oysters.

Center left- Atlantic Moon Snail (Polinices duplicatus), on Bay Mouth Bar, off of Alligator Point. The seagrass beds here contain a high diversity of predatory snails.

Upper left- Auger snail (Terebridae), on a blade of salt marsh cordgrass in Saint Joseph Bay.

Upper right- Marsh Periwinkle (Littoraria irrorata), on a blade of cordgrass in Saint Joseph Bay. Periwinkles graze on fungus growing on marsh grass, leaving scars on the grass.

Lower right- Horse Conch (Triplofusus papillosus), on Bay Mouth Bar at low tide. Horse conchs an the apex predator of intertidal seagrass beds in our area, and the main predator of the lightning whelk,

Up Next

The Seminoles are one group descended from the Muscogee; another are the Miccosukee. In a couple of weeks, we head out to Lake Miccosukee, where the water has dropped low enough for us to see one of its sinkholes. Waterfalls just outside of Tallahassee! Catch it on Local Routes- Thursday, February 9 at 8 pm ET on WFSU-TV