Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

Have you ever found oyster shells in the dirt of your backyard? If you have and you live in Tallahassee’s Myers Park neighborhood, then you might be looking at the remains of a powerful native village that rose to prominence over 500 years ago.

I was on a shoot for the first episode of our newest program, Florida Footprints. We were at the Florida Museum of History interviewing KC Smith about her involvement in the excavation of the Hernando de Soto winter encampment in 1987. Back then the city was abuzz about the artifacts being found so widely dispersed off of the appropriately named Apalachee Parkway. They had likely discovered the central Apalachee village of Anhaica, where de Soto spent the first winter of his North American expedition. People were finding piles of artifacts in their backyards. After the interview, I asked Smith how deep I’d have to dig to see if I had artifacts in my yard.

I was on a shoot for the first episode of our newest program, Florida Footprints. We were at the Florida Museum of History interviewing KC Smith about her involvement in the excavation of the Hernando de Soto winter encampment in 1987. Back then the city was abuzz about the artifacts being found so widely dispersed off of the appropriately named Apalachee Parkway. They had likely discovered the central Apalachee village of Anhaica, where de Soto spent the first winter of his North American expedition. People were finding piles of artifacts in their backyards. After the interview, I asked Smith how deep I’d have to dig to see if I had artifacts in my yard.

“Do you have oyster shells in your yard?” she asked.

Oyster shells? Evidently, these were the indicator of an Apalachee site. No one is sure what the shells were used for, though she believes they were used as small dishes. This is consistent with the interpretation in the photo above, taken at Mission San Luis, of scallop shells storing food stuffs. As Dr. Bonnie McEwan, Director of Archeology at the Mission, points out, “… Apalachees undoubtedly harvested and ate a lot of oysters when they were near the coast. But because there was no way to preserve them, they didn’t carry them.” So they weren’t eating oysters in Anhaica, so far from the coast, they were just bringing the shells back. Of all the shells they carried with them from Apalachee Bay, the most valuable belonged to a resident of the oyster reef, and to all of the intertidal habitats we follow: The lightning whelk (Busycon contrarium).

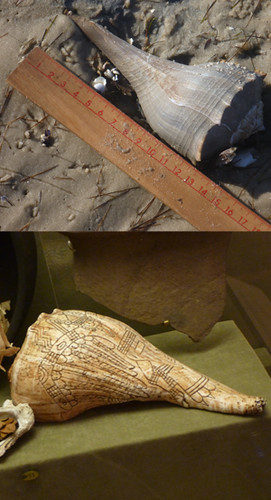

Much like our coastal shellfish are economically important today, lightning whelk shells were of particular value for the Apalachee. This had less to do with their meat than it did the size and shape of their shell. Whelks are predatory snails that get quite large, with an elegant sinistral (left hand) curve. I imagine that it’s the impressive appearance of a mature Busycon that led to their use in ritual life. “The outer shells with the columellae removed were used as dippers or cups,” Dr. McEwan said, “and these were used in Black Drink ceremonies. As we discussed, Black Drink was an emetic tea brewed from yaupon holly (Ilex vomitoria) leaves.” Anyone familiar with the effects of holly knows where the vomitoria species name comes from. The regurgitation caused by the Black Drink was a form of ritual purification, and was a central component of the ceremonies held in preparation for the fierce and occasionally deadly Apalachee ball game (the ball game is the focus of my segment in Florida Footprints). In the second photo to the right, you can see an interpretation of what a decorated Black Drink vessel looked like.

Much like our coastal shellfish are economically important today, lightning whelk shells were of particular value for the Apalachee. This had less to do with their meat than it did the size and shape of their shell. Whelks are predatory snails that get quite large, with an elegant sinistral (left hand) curve. I imagine that it’s the impressive appearance of a mature Busycon that led to their use in ritual life. “The outer shells with the columellae removed were used as dippers or cups,” Dr. McEwan said, “and these were used in Black Drink ceremonies. As we discussed, Black Drink was an emetic tea brewed from yaupon holly (Ilex vomitoria) leaves.” Anyone familiar with the effects of holly knows where the vomitoria species name comes from. The regurgitation caused by the Black Drink was a form of ritual purification, and was a central component of the ceremonies held in preparation for the fierce and occasionally deadly Apalachee ball game (the ball game is the focus of my segment in Florida Footprints). In the second photo to the right, you can see an interpretation of what a decorated Black Drink vessel looked like.

And whelks had value far outside of our area. The Apalachee were part of the Mississippian culture, and with it part of a trade network that stretched to the Great Lakes. Whelks with chemical signatures identifying them as from the Gulf have been found in Arkansas and Illinois. “In exchange for the shells,” Dr. McEwan said, “the Apalachees received artifacts made from ‘exotic’ or non-local materials such as copper, lead, mica, and steatite, all of which were found associated with burials at the Apalachees’ Mississippian capital– Lake Jackson.” Lake Jackson was capital of the Apalachee until about 1500. Judging by the materials for which they were traded, whelks were highly valued. Dr. McEwan elaborates on this. “In general, most of these items are found in association with burials of high status individuals throughout the Mississippian world since they conferred prestige.”

Here is a video of a lightning whelk roaming nearby St. Joseph Bay:

Since we’ve started the In the Grass, On the Reef project, one of the things that has interested me most is how the many cultures of this area, spanning thousands of years, have connected with the Gulf. I’ve enjoyed the illumination I’ve received on this little sidebar to the segment I produced. The next few episodes of Florida Footprints will move forward in time to cover our history since the Spanish arrived. Hopefully, we will later also look in the other direction at the people who left oyster middens on St. Vincent Island or to the Aucilla River, where the remains of the first Floridians and the mastodons they hunted continue to be found.

Since we’ve started the In the Grass, On the Reef project, one of the things that has interested me most is how the many cultures of this area, spanning thousands of years, have connected with the Gulf. I’ve enjoyed the illumination I’ve received on this little sidebar to the segment I produced. The next few episodes of Florida Footprints will move forward in time to cover our history since the Spanish arrived. Hopefully, we will later also look in the other direction at the people who left oyster middens on St. Vincent Island or to the Aucilla River, where the remains of the first Floridians and the mastodons they hunted continue to be found.

My co-producers on this episode are Mike Plummer and Suzanne Smith. Suzanne is covering the de Soto excavation and the discovery of Anhaica. Mike is looking at the Spanish mission period in our area.