Let’s rethink how we garden for caterpillars. What if we focused on quantity over “quality?” Quality is in quotes because when it comes to caterpillars, a quality caterpillar means a caterpillar we like. I’ve written several blog posts on the larvae of large, showy butterflies. People want to know about raising monarchs, swallowtails, and gulf fritillaries. We buy plants for their young so that we’ll see the adults on our flowers.

But what if our goal was filling our garden with as many caterpillars as possible, of every type?

That’s exactly what Doug Tallamy wants people to do. Tallamy is an entomology professor at the University of Delaware. He’s best known for a 2018 paper he co-authored that linked the decline of U.S. songbird populations with a decline in native plants. Essentially, people are using more exotic plants in their yards and other human-made spaces. Native insects have formed relationships with native plants over millions of years; as Tallamy explains, each plant-eating insect has evolved to overcome specific plants’ chemical defenses. When those plants become scarce, insects may not be able to find a new food source.

This is a problem for songbirds – 97% of their diet is insects. Tallamy says that of all insects, caterpillars provide the most energy that moves up the food web to insectivores. So if we buy more native plants, we can attract more caterpillars and better feed birds, right?

Yes… and no.

What plants host the most caterpillars where you live?

I was listening to the Growing Greener podcast when Doug Tallamy said something that caught my ear. He said that not all native plants are equal. This makes sense. Some plants have more ecological value than others. He went on to say, though, that most native plants don’t offer much value in terms of the number of moth and butterfly caterpillars they host. He wanted people to focus on what he calls keystone plants. His research shows that 14% of native plant species are larval hosts for 90% of caterpillar species.

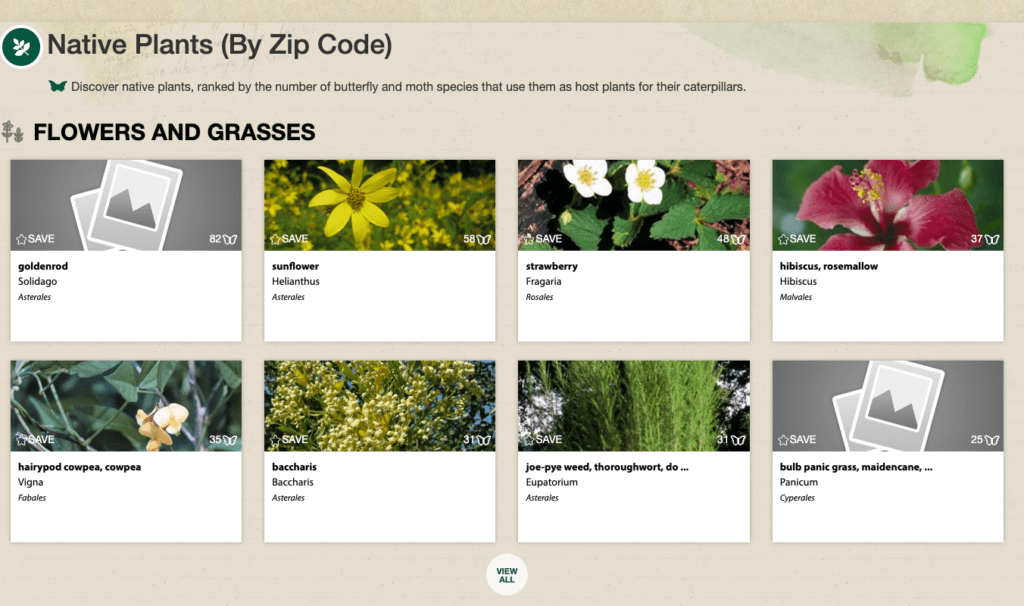

Tallamy says that with a few smart purchases, you can get the most bang for your buck, and provide birds with the largest quantity of food. He then mentioned that the National Wildlife Federation has an online plant finder where all you have to do is type in your zip code, and you get a list of the most productive plants for caterpillars.

What a cool tool! If all you cared about was caterpillars.

Now, I do of course care about caterpillars, and not just large, showy butterfly caterpillars. But I also care about bees and wasps, and overall insect diversity. To me, this is one more tool to help guide me as I try to make as complete a habitat as I can in the relatively small confines of my yard.

I’ve gone through the list for the Tallahassee area, and I have some notes. How does this list overlap with our list of the best plants for bees? How many might grow as weeds in our yards, and which would we have to buy or start from seed? Let’s see.

A few notes before diving in

- This is a list of larval food hosts for both butterflies and moths. Goldenrods (Solidago genus) host 82 species of Lepidoptera, but none of the fifteen species they list are butterflies. I mention this to set a reasonable expectation of what this list is trying to accomplish. I don’t want to give anyone the idea that these plants will fill their yards with butterflies. The list is more focused on food webs than on pollination specifically. Though, of course, goldenrod is a valuable fall-blooming nectar source, and moths are pollinators.

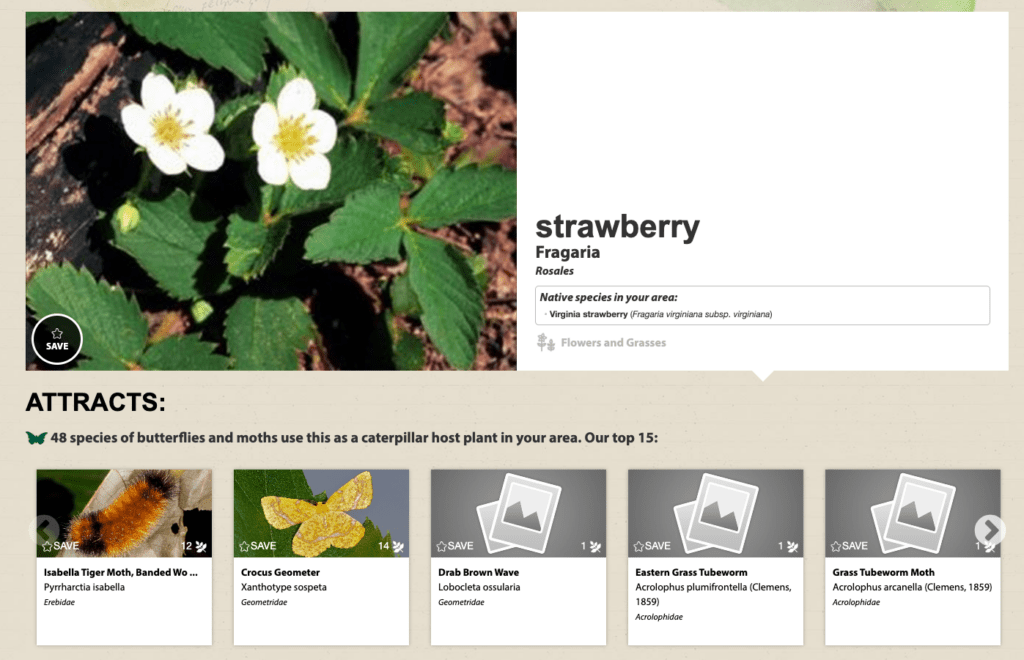

- The plants are listed by genus. When you click on each box, you get a list of the species of the genus in your area. Beneath the list, NWF displays their top fifteen moth and butterfly species that host on the plant. I wish it was all of them.

- Plants are sorted into two categories: Flowers and Grasses, and Trees and Shrubs. You may not think about grasses when planning a pollinator garden, but quite a lot of moths and smaller butterflies host on them. And, yes, trees and shrubs are critical. That was my revelation when we were putting together our list of plant species for bees; but as we see here, even wind-pollinated trees are important to pollinators.

What are the top Flowers and Grasses for caterpillars?

- Goldenrods (Solidago): 82 caterpillar species

- Sunflowers (Helianthus): 58 species

- Strawberry (Fragaria): 48 species

- Hibiscus, rosemallows (Hibiscus): 37 species

- Hairypod cowpeas (Vigna): 35 species

- Baccharis (Baccharis): 31 species

- Joe-Pye weed, thoroughwort, dogfennel, common boneset (Eupatorium): 31 species

- Bulb panic grass, maidencane, winged panicgrass, panicgrass, switch grass (Panicum): 25 species

- Geranium (Geranium): 25 species

- Lupines (Lupinus): 25 species

- False indigo, indigobush, leadplant (Amporpha): 24 species

Let’s take a closer look at the top flowers and grasses for caterpillars

These plants are good for caterpillars, but how about adult pollinators? Would all of these plants grow in your yard? Which are in nurseries, and which might grow as weeds?

1. Goldenrods (Solidago)

Goldenrods typically bloom in October and November, making them an important source of nectar late in the year. They can spread and become dominant in disturbed areas, and different species thrive in both wet and dry environments. Because they are so plentiful at a time when the blooms of many other flower species are fading, goldenrods are a critical nectar source for migrating monarchs.

This one made our bee plants list.

2. Sunflowers (Helianthus)

Another genus featured on our bee plant list. Like goldenrod, rayless and narrowleaf sunflowers are fall bloomers. Woodland sunflowers peak in the summer. Dune sunflowers are native to coastal areas but will grow in most Florida yards, and bloom for much of the year.

3. Strawberry (Fragaria)

Yes, we have a species of native strawberry, the Virginia strawberry. It is in the same genus as the garden strawberry we buy in grocery stores, which is of European origin. And it hosts 48 caterpillar species!

These are sometimes available in nurseries. Some of the same caterpillars may host your garden strawberries.

4. Hibiscus, rosemallows (Hibiscus)

Our native hibiscus are found in wetlands, but they are cultivated for garden use as well. They can be used as ornamental shrubs.

5. Hairypod cowpeas (Vigna)

As far as I know, these are not commercially available. I checked with Native Nurseries of Tallahassee, and they have not carried it.

6. Baccharis (Baccharis)

I checked iNaturalist for Baccharis in Leon County, and I found a lot of observations for one species: the groundsel tree, or saltbush (Baccharis halimifolia). It’s a shrub in the aster family, which blooms from late summer to early fall. One just volunteered in our yard, and so I’m still getting to know it. Asters (which include goldenrods and sunflowers) are typically high-value nectar plants. Groundsel trees can be weedy but have good wildlife value if you have space for them.

Elizabeth Georges at Native Nurseries says they have carried saltbush, but their tree carrier stopped providing it because it is so weedy.

7. Joe-Pye weed, thoroughwort, dogfennel, common boneset (Eupatorium)

The genus Eupatorium used to include Joe-pye weed. Joe-pye weeds were moved to the genus Eutrochium, which is listed separately as hosting two species. Joe-pye weed is a high-value nectar plant, as are bonesets and mistflower (Eupatorium coelestinum). They can become weedy.

Dog fennel grows as a weed, but I leave a spot for a cluster of them in the yard. I was doing this for species diversity, but I’m happy to know it may host quite a few caterpillars.

8. Bulb panic grass, maidencane, winged panicgrass, panicgrass, switch grass (Panicum)

Dichanthelium grasses are nowhere to be found on the list, so I wonder if they were grouped with Panicum, the genus to which they used to belong. Panicgrass is taller, and many of the Leon County species observed on iNaturalist are in or around lakes and wetlands. Dichanthelium is much shorter and commonly volunteers in gardens.

9. Geranium (Geranium)

We have one native Geranium, Carolina cranesbill. It’s a ubiquitous lawn weed that starts to sprout in late fall and blooms in early spring. The small flowers are some of the first we see in our yard every year, feeding smaller pollinators such as hoverflies. Now I know this plant can host any of twenty-five caterpillar species.

10. Lupines (Lupinus)

I had lupines on our bee plant list. The two species native to Leon County grow in dry, sandy soils. They’re common in the Munson Sandhills in the south of Leon County. I’m told each is easy to grow from seed but doesn’t transplant well. So you won’t find either at a nursery.

Both bloom early in the year and sundial lupine hosts a butterfly that’s rare in the southeast, the frosted elfin.

11. False indigo (Amorpha)

Elizabeth Georges at Native Nurseries says they have carried false indigo in the past, but not consistently. She has asked her wildflower provider to start growing it and is hopeful that they are successful. False indigo is a shrub with showy flowers.

Read More: Feeding caterpillars in your north Florida Garden

- Raising monarch, black swallowtail, giant swallowtail, and longtailed skipper butterflies, with photos of every life stage.

- Raising gulf fritillary caterpillars (passion flower caterpillars), with photos of every life stage.

- Caterpillar supermarkets: a list of the wildflowers and trees/ shrubs that host the most moth and butterfly caterpillar species.

- A lot of insects are out to kill your monarch caterpillars. It’s a sign that your garden is healthy.

What are the top Trees and Shrubs for caterpillars?

- Oaks (Quercus): 395 species

- Beach plum, cherry, chokecherry, peach, plum, sweet cherry, wild plum, almond (Prunus): 247 species

- Hickory, pecan, pignut, butternut (Carya): 191 species

- Willows (Salix): 190 species

- Birch (Betula): 172 species

- Crabapple, apple (Malus): 171 species

- Maple, boxelder (Acer): 171 species

- Pines (Pinus): 171 species

- Aspen, cottonwood, poplar (Populus): 156 species

- Blueberries (Vaccinium): 150 species

Caterpillar trees in the urban canopy

The first thing that sticks out is how many more caterpillar species are hosted by woody plants than wildflowers and grasses. Trees are the foundation of our local terrestrial ecosystems.

Planting a tree is more of a commitment than planting wildflowers, and you’re more constricted in where you can plant a tree. One consideration is how common a tree is in your area. Years ago, we took a look at live oaks and Tallahassee’s Urban Forest Master Plan. From a survey of trees on public land, the City of Tallahassee determined that Carolina cherry-laurels were the most common trees in Tallahassee, followed by water oaks, laurel oaks, and live oaks.

Right off the bat, at least 39% of our urban canopy is made of species from the two most caterpillar-productive genera (plural of genus). But in urban forestry, diversity is a key to the health of a city’s canopy. The master plan (and other foresters interviewed for the story) called for no one species to exceed 10% of the canopy, and no genus to exceed 20%. Cherry-laurels make up 15% of the canopy, and the top three oak species make up 24%.

So, while these may be the trees that would potentially host the highest number of caterpillars, they are already well-represented. By planting other trees, you create opportunities for other species of moths and butterflies and diversify the canopy.

A few notes on the top caterpillar trees and shrubs in Leon County, Florida

- Carolina cherry-laurels, water oaks, laurel oaks, and pecan trees are considered weak-limbed. A goal of the Urban Forest Master Plan is to make Tallahassee more resistant to the increasing number of strong storms that head our way, and these trees are more likely to down a power line or cause damage to a house than stronger species.

- Two genera on this list are featured on our bee plant list. Cherry and plum trees (Prunus) are some of the first plants to bloom in our area, and they produce prodigious clusters of white flowers that early flying bees love. Cherry-laurels are well represented in our canopy, but there are other Prunus options, like Chickasaw plum or hog plum.

- The other bee plant on this list is blueberries. Trees and shrubs produce many of the year’s early flowers, and feed many specialist bees, such as the blueberry digger bee.

- Caterpillars don’t just need the trees, but also the ground beneath the trees. As Tallamy told a gathering of gardeners in North Carolina, many caterpillars fall from trees to make their chrysalis in soil or leaf litter. This is much the same habitat needed by nesting bees and many other insects, especially over the winter. Do you let your leaves lie beneath your trees over the winter? Are there bare patches of soil in your turgrass?

Where do some of my other favorite pollinator plants rank?

Many of the workhorse pollinator plants in my yard were not in the top ten of either list. Most are in my garden for their nectar value, while others I planted specifically to attract caterpillars.

- Fanpetals (Sida): 18 species

- Ironweed (Vernonia): 18 species

- Mimosa, powderpuff, sensitive plant (Mimosa): 17 species

- Milkweeds (Asclepias): 15 species

- Partridge pea, sensitive pea (Chamaecrista): 14 species

- Brown-eyed Susan, black-eyed Susan, coneflower (Rudbeckia): 11 species

- Hedgenettle (Stachys): 8 species

- Aster (Symphyotrichum): 7 species

- Beebalm, wild bergamont (Monarda): 7 species

- Passionflower, passion vine (Passiflora): 7 species

- Devil’s walkingtick (Aralia): 6 species

- Sage (Salvia): 6 species

So, what do I make of this list?

My favorite larval food plants aren’t so highly ranked

I plant milkweed and passion vine specifically for caterpillars – those that become large, showy butterflies.

The monarchs we raise don’t stick around to visit our flowers. Instead, we plant milkweed to help a species facing serious population decline. Plenty of them do get eaten, though.

The value of passionflower lies not in how many species it hosts but in the value of those few species that use it as a host. Three of the seven caterpillars that eat its leaves are large butterflies: gulf fritillaries, variegated fritillaries, and zebra longwings. These are some of the most common butterflies we see visiting flowers in Tallahassee. But what of their value in the garden food web?

For the two years I’ve had passionflower in the garden, gulf fritillaries and zebra longwings have prolifically filled its leaves with their caterpillars. Sunflowers and dog fennels potentially host more species, but I don’t see these plants covered in caterpillars. That doesn’t mean they aren’t hosting on the plant, but caterpillars aren’t conspicuously covering them.

This list is compiled from a database looking at what plants grow in your area, and what caterpillars in your area host on those plants. It doesn’t tell you which of those caterpillars are most common, or the sizes of the caterpillars. Passion vine is filled with large, juicy caterpillars, many of which get eaten. That’s a lot of energy moving up the food web.

Fanpetals

This has long been one of my favorite weedy shrubs, in large part because it hosts checkered-skipper butterfly caterpillars. Its small, yellow flowers are well-visited by bees and small butterflies. It also hosts insects other than those 18 moth and butterfly species.

One day I noticed a cardinal pecking at fanpetal leaves. When it was done, I took a closer look and found several small insects: scentless bugs. I’ve found scentless bugs on fanpetals every year since then. These plant eaters are related to stinkbugs and are a food source for birds.

A note on hedgenettles

I clicked on the hedgenettle link on this list and neither of the two species listed was Stachys floridana, aka Florida betony. I’m not sure why it was omitted. This is an early-blooming weed that some folks consider a problem because it spreads aggressively. It also dies back after April and is a nectar source for early flying bees. It blooms concurrently with blueberries, and blueberry digger bees will visit it about as much as they visit blueberry flowers.

Beebalm and devil’s walkingstick

Again, caterpillars aren’t the only measure of a plant’s value. These are two high-volume nectar plants that attract a high diversity of pollinator species all at once. These plants are especially valuable to solitary nesting wasps. Digger wasps and scoliids may look mean, but they are not aggressive to humans. They are aggressive to plant-eating insects, paralyzing grasshoppers and beetles to bring back to the nest for their larvae. And also, who wouldn’t want to see the impressive cicada killer wasp?

What about Bidens alba?

This plant is everywhere, and its leaves do get eaten. Any plant with at least one caterpillar is on the list, and this plant hosts at least one: the dainty sulphur. So why was it left off this list? My theory is that they don’t consider plants in the Bidens genus to be native. Most sources list Bidens as native, but there is increasing speculation that they were introduced onto our landscape. This entry from UF/ IFAS has Bidens alba as native and introduced, all in the span of two sentences:

Common beggarticks or spanish needle (Bidens alba) is a native Florida landscape weed. This species is indigenous to Central and South America and was introduced to North America.

Mid-Florida Research and Education Center / University of Florida IFAS

Obviously, the author was using the word indigenous as I would use native, and the word native to mean something that includes naturalized plants.

I’ve been reexamining what I think of this plant lately, as I see how much ground it covers and how easily it spreads. I, like many others, let it spread because so many pollinators visit its flowers. But how many insects eat its leaves? Should we give so much space to a plant that may not feed a proportionately large diversity of caterpillars and other bird food?

Building a well-balanced ecological garden

Take a deep breath. The burden of supporting all of north Florida’s wildlife is not on you alone. We all do what we can to help, but we’re not restoring longleaf pine savannas in our yards (well, some of you might be).

I share this tool and its list of plants as one more source of information. Myself, I have a garden full of wildflowers that provide nectar throughout the year, and larval food for several species of butterflies. I look at this list and see that I could add one or two different plant species and increase my caterpillar diversity. My garden already changes from year to year as I keep learning and tweaking the formula. This list helps me figure out a few more tweaks for next year.

You may or may not approach your garden the same way I approach mine. However, if you are interested in helping songbird populations, take a look and see if any of the plants on these lists might find a happy home in some corner of your yard.

Apps and Citizen Science mentioned in the Backyard Blog

iNaturalist

Identify plants, animals, lichens, and fungi in your yard. Other users correct your identifications if you’re wrong, and even if they don’t, it can be a good springboard to further research.

Seek by iNaturalist

Instant identification, and it doesn’t record your location. This is a good option for kids with phones.

Monarch Larva Monitoring Project

Enter information about monarch caterpillars in your yard, and help researchers get a sense of the health of the monarch population that year, and how and when they’re migrating.

Great Sunflower Project

Record the number of pollinators visiting your flowers, and help researchers map pollinator activity across the country.

Dig Deeper into Backyard Ecology

What can we do to invite butterflies, birds, and other wildlife into our yards? And what about the flora and fauna that makes its way into our yards; the weeds, insects, and other critters that create the home ecosystem? WFSU Ecology Blog takes a closer look.