North Floridians are drawn to the Aucilla Sinks because they’re unlike almost anything else in Florida, and a little mysterious. A trail winds past rocky pools and short streams lined with tall walls of limestone. What we’re seeing is bits and pieces of the Aucilla River. The river runs aboveground to the north and to the south of here, but I wonder- what happened to it in the middle? I wanted to know, so I invited geologist Harley Means for a hike.

We don’t associate Florida with large rocks. What Harley revealed to me, though, is that the Aucilla Sinks are in fact uniquely Floridian. It’s the Florida beneath us, exposed.

Harley is the Assistant State Geologist for the state of Florida. Our state’s geology is almost entirely under us- a large, limestone aquifer that provides our state with abundant water. In our previous adventures with Harley, we’ve gone where groundwater interfaces with the surface. It’s in these places where we can start to visualize the many pathways- big and small- through which water makes its way into our taps, and into our remarkable springs.

Aucilla Sinks Trail at a Glance

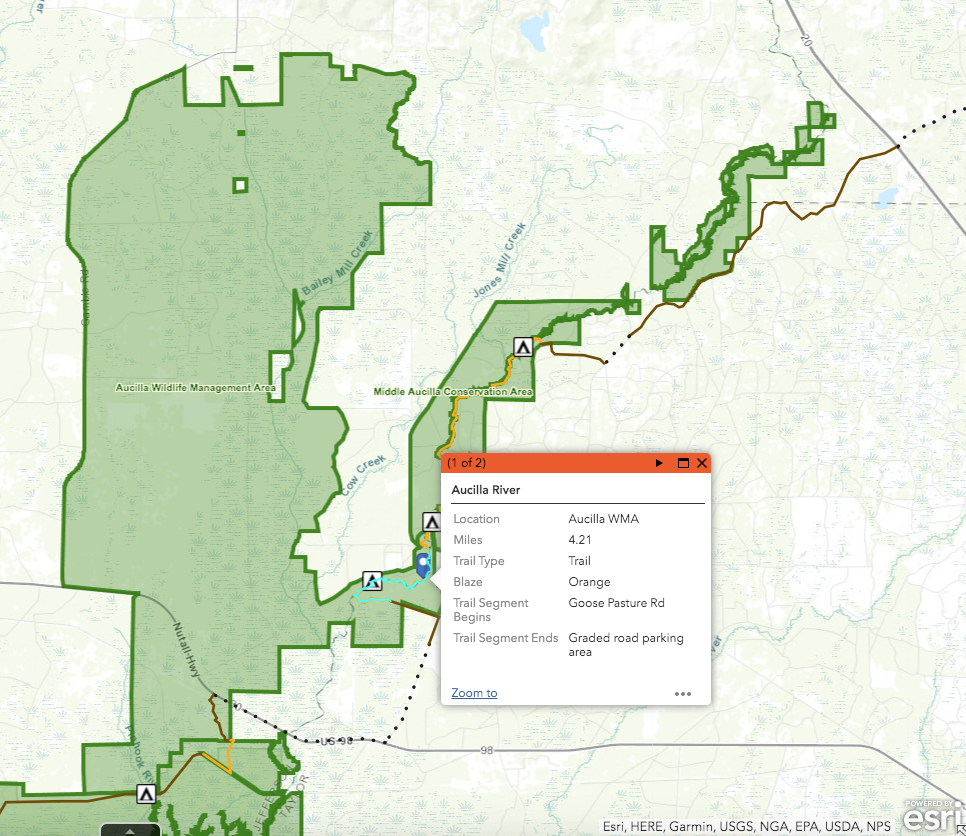

The Aucilla Sinks segment of the Florida National Scenic Trail is 4.21 miles long.

The trailhead is located on Goose Pasture Road (link to marker in Google Maps) in the Middle Aucilla Wildlife Management Area. You can also enter from a parking area at the other end of the segment.

Here’s a link to the trail segment from the Florida National Scenic Trail segment map. It’s not a map PDF or basic web page like I usually link to. It’s a GIS (Geographic Information System) map, which is interactive, but might take some getting used to if you haven’t used one before.

The trail is best enjoyed over the winter. I did find a few ticks on me after our January hike, but I found many more after hiking the trail in late March (not to mention the mosquitos then).

The Aucilla River Goes Under

When you get to the Goose Pasture Road trailhead, you can go in one of two directions. One leads you south to the sinks, while another leads you north to the Aucilla River. If you plan for a longer hike, you can follow the Florida Trail along the river and all the way to, well, the Everglades. With access points and campsites every few miles, you can plan a Florida Trail hike of a couple of hours, days, or months.

But back to the Aucilla.

After a few minutes of walking, you can reach the river where it goes under. Everything carried by the river ends up in a pile over the swallet, from trees and branches to every piece of trash to fall off of a boat or get washed into the river.

Turning back from the river and crossing Goose Pasture Road again, you see the river rise and fall periodically, into and out of the ground. These are the Aucilla Sinks. If you look at the sinks on an aerial map, they follow more or less a singular path, like a single stream that finally emerges at Nutall Rise, and continues to the Gulf aboveground.

It looks like an underground river, but it isn’t really.

“Let’s sort of get that out if the way real quickly,” Harley says. “The concept or idea of a river flowing underground is not quite what geologists would call it. And what you’re seeing here is, you’re seeing the ancient conduit system that was sculpted by groundwater over many, many thousands, and probably even millions of years, Rob.”

Seashells and Limestone | Florida’s Ancient History Beneath Your Feet

When the river went under, it entered the maze of water that is the Floridan Aquifer.

“This is an interconnected pipe of all kinds of porosities, and cave systems, and little tunnels where once that water gets into the underground aquifer, it has the ability to flow quite volumously.

“But this is the kind of thing that exists under almost the entire state of Florida.”

In this limestone, we can see Florida’s relationship with water over tens of millions of years. Our state is known for its coasts- the beaches, yes, but also those intertidal ecosystems that serve as nurseries for so many marine animals.

Next time you’re at one of those beaches, or enjoying oysters, take a look at the shells. Mollusks like conchs and whelks, scallops and clams- when they make their shells, they’re making what may one day become rock.

“Limestone is comprised primarily of the mineral calcite,” Harley says. “But sometimes the calcite can come in different forms. Some of the marine organisms that you’ll find fossils of in here, actually you’ll find the molds of them because they dissolved away. But those marine animals make their tests, or their shells, if you will, out of either aragonite or calcite. And aragonite is a little less stable form of calcium carbonate.”

Imagine a Florida of thirty million years ago, entirely under the ocean. It wouldn’t have looked too different than what’s off our coast today. The salt water creatures from back then are responsible for the fresh water we enjoy today.

Limestone, Always Dissolving Away

Limestone is often described as a sponge; it’s porous, and water can soak into the tiny spaces within it. Over geologic time, water enlarges those spaces.

“Rainwater is naturally acidic,” Harley says. “Once rainwater gets into and percolates into soils and sediments, it can pick up additional acidic things like tannins and other kinds of organic acids, and it turns the water black.”

That acid eats away at the limestone.

Limestone lets water in, and lets it move. Over time, that moving water increases the limestone’s capacity to carry it. You can see holes in the rock walls at Aucilla Sinks, as big as a marble, or a baseball, or a football. Those become little tunnels. Eventually you get cave systems like in the Wakulla Springs System, or at Merritt’s Mill Pond.

When those large openings are near to the surface, they might cave in and become sinkholes. At Lake Miccosukee, Harley showed us how sinkholes become active and continue to grow. At Fred George Basin Greenway, he showed us a sinkhole in the process of caving in, and we see that along the Aucilla Sinks trail.

As Harley has shown us, the processes that created this topography are still at work, and the landscape continues to change.

Geology in Action on the Aucilla Sinks Trail

This is a good trail to hike slowly, and enjoy the views. There are places where you can climb down off the trail and take a closer look at a sink. Like any river, the Aucilla goes through dry/ flood cycles, and the sinks can flood as well. Be aware that the area around the sinks might be mucky (I may have taken a tumble).

There are a couple of spots where you can see the land slope down into a bowl, or series of bowls. Here, the sinks haven’t caved all the way in. In the future, they may open up and carry water in a different direction.

I follow Harley into one of these sinks-in-progress. He points out that it’s actually a row of depressions. “You can clearly see there’s a linear trend here.” This is from a long fracture in the underlying limestone. “That’s important, because once that fracture is created in the limestone, now you’ve got a preferential path for water to flow.”

And, again, once water starts flowing into it, the passageway enlarges. Over time, this could be another open sink with water flowing in a new direction. In another spot, Harley points out where two flowing channels come together. It reinforces the notion that, once it enters the aquifer, it’s not a single flowing stream.

The Aucilla Sinks are not only visually fascinating, but the geology that created it, and that continues to shape it, is equally fascinating. It’s a highlight among highlights in our geologic region of Florida.

Water in the Woodville Karst Plain

Throughout north central Florida runs an ancient coastline called the Cody Escarpment. It’s a geologic feature that ends up in a lot of my ecology stories, because it has a huge influence on our area’s biodiversity.

“Now the headwaters of the Aucilla River are up in south Georgia.” Harley says. We’ve visited one of those headwaters, Thomasville’s Lost Creek. “So we get a lot of surface water that flows as the Aucilla River, over the Tallahassee clay hills until it goes over that feature we call the Cody Escarpment. And then once that water reaches the Woodville Karst Plain, in fairly short order, you start to see the river disappear through these karst features, through these tunnels if you will.”

On the Woodville Karst Plain, a thin layer of sand covers the aquifer. Water enters more freely here. The Saint Marks River also goes underground and reemerges. In the Munson Sandhills, porous spots in the aquifer form ephemeral wetlands, which fill and empty depending on the fullness of the underlying aquifer. And then there are springs, including North America’s largest, Wakulla Spring.

Springs feed the Aucilla’s main tributary, the Wacissa River. The clear Wacissa flows entirely from aquifer, originating just south of the Cody Escarpment. The dark Aucilla flows down out of the Red Hills before entering the aquifer.

Enjoying the Aucilla and Wacissa Rivers

Both rivers, and the area around them, are a natural playground. Harley says he learned to swim in the Wacissa, and my own children have enjoyed swimming and jumping off the rope swing at the headwaters. We’ve also had family canoe trips with friends here, exploring the spring runs just off the river. When they’re a little older, I’d love to take them on the Slave Canal, which connects the Wacissa to the Aucilla. And I’d really love to bring them here to the Aucilla Sinks Trail.

Each river shows us something a little different about the Florida beneath us.

“It’s a beautiful area,” Harley says. “A great place to hike. But what you’ll really take away from it is the dramatic geology that was etched by water. And not only that, you can envision that this series of rises and falls of the Aucilla River is just once example that’s near enough to the surface, where you can see it, of all the plumbing that’s going in the deep subsurface beneath us.

“And it’s one of the reasons Florida is such a unique state, and we are blessed with an abundance of water in our state. It’s because we live on this giant sponge.”

The Florida National Scenic Trail at a Glance

The Florida Trail is the only National Scenic Trail contained entirely within one state. With proper planning, you could hike from the Everglades to Pensacola.

The US Forest Service’s Trail web site says it’s approximately 1,500 miles long. The reason the length is approximate is that there are alternate trails, and segments are rerouted from time to time.

The trails runs through public land as much as possible. Sometimes, the Florida Trail Association and USFS come to an agreement with a private landowner. As a last resort, the trail follows a roadway.

In 2017, we hiked a section that had been rerouted from a roadway, and into the Nokuse Planation along the Choctawhatchee River. The Florida Trail passes through some exceptional natural wonders of our area. This includes the Bradwell Bay Wilderness, the Cathedral of Palms, and the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge.

Orange blazes mark the Florida National Scenic Trail.