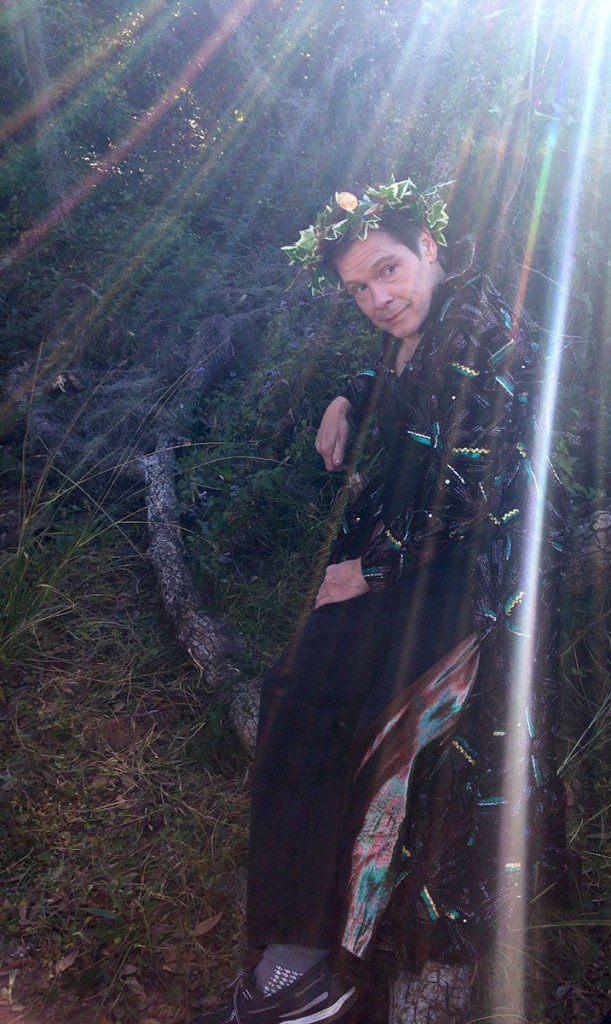

Video: William Shakespeare grew up in nature, and it shows through in his plays. We visit Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy with wilderness survival instructor and star of National Geographic’s Live Free or Die, Colbert Sturgeon. As we walk down from Tall Timbers to Lake Iamonia, we gather wild food and explore Shakespeare’s knowledge of plants and their uses. Once again, FSU’s Dr. Bruce Boehrer makes the connections in this second installment of EcoShakespeare.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

Oberon, the king of the fairies, sends Puck to find an aphrodisiac flower in the woods outside of Athens. Puck then uses a potion derived from the flower on the queen of the fairies, Titania, to set up some of the most comical moments of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

If William Shakespeare were alive today, would some local BBC producer ask him to show the plants of his native Warwickshire on camera? Or would he consider flying to Tallahassee to sample persimmons growing by Lake Iamonia for WFSU? In our year-end post for 2014, Dr. Bruce Boehrer starts to paint a picture for us of a man whose classic works are inextricably tied to his country upbringing. It’s cool to think that the things that inspired him also inspire us here in north Florida. He might have been right at home in the Red Hills region of farms, forests, and rivers; perhaps incorporating tupelo swamps and RCW cavities into his verse.

In the scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream that we explore in the video above, we see that he likely had a good knowledge of the plants that grew around him. Where Colbert Sturgeon extols pine needles’ abundance of vitamin c or the curative properties of St. John’s Wort, Shakespeare was versed in the magical properties of plants. It’s reflective of a contemporary world view, just as his sense of ecology in our last video was rooted in interpersonal relationships. He didn’t have the benefit of our science, but it is interesting to note that he had a general understanding of cause and effect in nature. He might not have understood greenhouse gases and their role in climate change, but he could conceive that people could cause an imbalance that would change the weather and upset plant productivity. Likewise, he knew that different plants had the ability to affect us, even if he didn’t understand the chemical basis for this. Magic is just a name for all that we don’t yet understand.

In our final installment of EcoShakespeare, we’ll explore what Dr. Boehrer calls Shakespeare’s “proto-ecological” sensibilities. Unlike the other leading playwrights of his day, Shakespeare didn’t have a university education. Yet he still learned classical literature, inventively mixing drama and comedy, the high-brow and the down-home. It’s much the same with his perception of the natural world. Two-hundred-and-fifty years before the word ecology is coined, he sort of intuitively gets it. It’s nothing less than you’d expect from a man whose works still resonate four-hundred years after they were first written and enjoyed by audiences.

As we walked down from Tall Timbers to Lake Iamonia, this is what Colbert collected. The bright purple beauty berries are attractive but nearly flavorless. The duller colored berries are sumac. When we shot this in early November, they were slightly out of season, whereas the persimmons were not quite ripe. Our local variety of persimmon is intensely bitter until it ripens. As Colbert was making his medicinal tea, we realized that we had no cups or straws, so he fashioned this straw from a bamboo stalk and we all sipped straight from the teapot.

Next week, we conclude EcoShakespeare with a song of protection for Wakulla Springs. Nitrates, algae, hydrilla, and dark water have weakened one of our area’s foremost ecological resources. Just as Titania’s fairies cast a spell to protect her from spiders and snails, the Friends of Wakulla Springs and the Wakulla Springs Alliance work to protect the beloved local tourist destination and wildlife habitat.

Special thanks to WFSU’s partners for this EcoShakespeare segment, The Southern Shakespeare Festival and Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy. EcoShakespeare is funded by a grant from WNET’s Shakespeare Uncovered. Catch their take of a Midsummer Night’s Dream Friday, January 30 at 9 pm ET on WFSU-TV. For more information on Shakespeare Uncovered and WFSU’s associated TV and Radio projects, visit our Shakespeare Uncovered web site.

Shakespeare Uncovered is made possible by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Major funding is also provided by The Joseph & Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation, Dana and Virginia Randt, the LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust, the Lillian Goldman Programming Endowment, The Polonsky Foundation, Rosalind P. Walter, Jody and John Arnhold, the Corinthian International Foundation, and PBS.