Video: We accompany Jim McClellan, author of Life Along the Apalachicola River, as he scouts turkey hunting locations and fishes in Iamonia Lake, an oxbow of the Apalachicola.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

We met Jim McClellan at 5:00 am in the parking lot of a Blountstown McDonalds. He took us to the Iamonia Lake Hunting and Fishing Club, from where we departed for Iamonia Island (surrounded by Iamonia Lake on one side and the Apalachicola River on the other). We sat in the darkness, backs against a tree, unseen mosquitos conducting a blood drive from any skin we left exposed. Turkey season began the following day; on this day we sat and listened, communicating by whisper. I wondered, would Jim’s potential prey see the little red light on the side of my camera battery?

This is how Jim McClellan grew up. This is the kind of thing Jim writes about in his book, Life Along the Apalachicola River. His family has lived in Calhoun county for seven generations; Jim himself is fifth generation. Sitting here with his back to a tree in the forested flood plain of the Apalachicola River, he is continuing a familial relationship with this land and water that goes back over 150 years. Within Jim’s own lifetime, however, he has seen Iamonia Lake change.

This row of willows took root in Iamonia Lake during a low water event. Now firmly established in the channel, the trees are accumulating silt. The Apalachicola River system relies upon its many sloughs and streams. The banks of these waterways provide important foraging grounds for the river’s fish. Channels like this provide nutrients to the Apalachicola Bay estuary. What happens when the channels are narrowed or become blocked?

“I’ve talked to people in their sixties, people in their seventies, people in their eighties,” Jim said as he guided us to the main river channel later in the morning. “The periods of low water that we’re seeing now are things that those folks haven’t seen in their life.”

We slowed down now and then to squeeze between willow trees that took root in Iamonia Lake’s stream bed when water was low. “In my lifetime, this has been an easily navigable waterway from where we are now all the way out to the river.” In his lifetime, he has seen Iamonia Lake, an oxbow which had once been part of the main Apalachicola River channel, cut off from the river on both ends. This was just a couple of years ago, he said; I imagine this was during the record low flows of 2012. That year, fish didn’t bite and he couldn’t find frogs.

As we returned from the fogged out Apalachicola, he set bush hooks on low branches. I’ve been seeing those since I started paddling out here in 2012. These fishing hooks are baited and hung to be retrieved later in the day or early the next. They are usually marked by bright tape- all except the one that caught my shirt on the last day of RiverTrek 2012. On that trip, I saw plenty of the river, but only superficially experienced the river culture Jim writes about in his book. I saw bush hooks. On the Estiffanulga sand bar, I awoke to the sounds of barking dogs and boats departing the ramp across the river in the early morning. I saw hunting dogs in a floating kennel south of Wewahitchka. Through Jim’s book, I get a better sense of that world.

- Jim didn’t catch any turkeys that weekend. We went out with him on a Friday; Turkey season started that Saturday. He did hear some turkeys on Sunday, and caught “a boatload of fish.”

- This is Jim’s first book, but he is a writer by trade. He was a speechwriter for Governor Lawton Chiles, Press Secretary for Lt. Governor Buddy MacKay, and Communications Director for the Florida Department of Commerce. He currently does marketing for an e-mail and web security firm in Pensacola.

- Jim gave us more stories than we could fit into a single video. You can watch those, which paraphrase stories in his book, here.

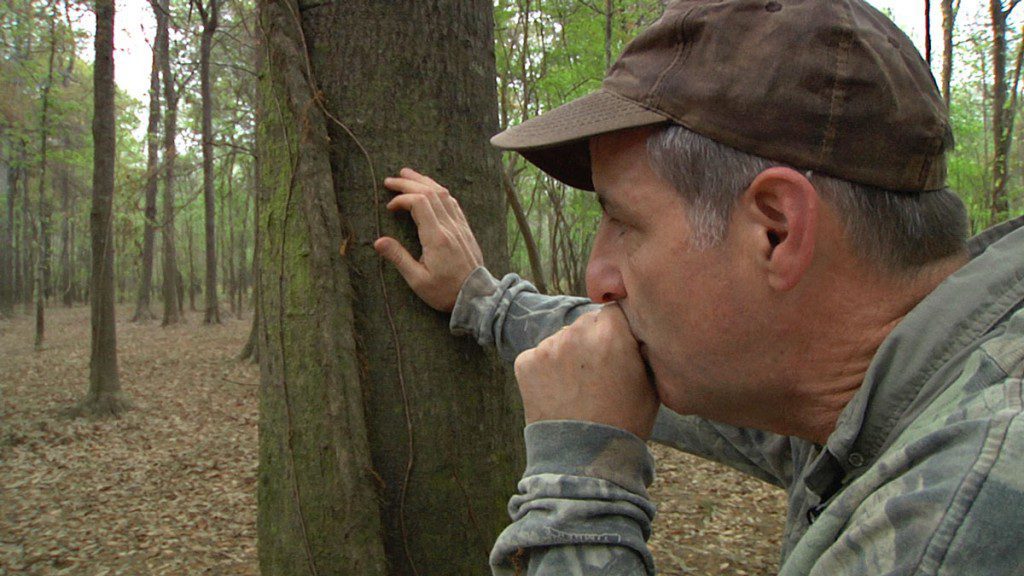

Jim calls a turkey. As he explains in the video, turkey hunters go against nature by doing this. Males are the ones that are hunted, but they are also the ones who call females to them. Jim is imitating a female calling a male.

Hunting Along the Apalachicola River

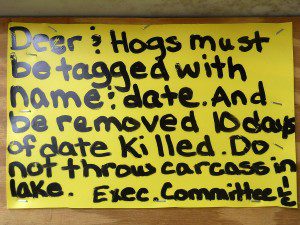

Jim and his family hunt on private land. But, as we’ve covered in the past, there is plenty of public land along the Apalachicola River. If you’re interested in hunting along the river, check out the Apalachicola National Forest, Tate’s Hell State Forest, and The Apalachicola Wildlife and Environmental Area. The Northwest Florida Water Management District manages two sites where you can hunt along the river: Florida River Island and Beaverdam. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has a hunting page on their website that’s full of resources and information.

Jim and his family hunt on private land. But, as we’ve covered in the past, there is plenty of public land along the Apalachicola River. If you’re interested in hunting along the river, check out the Apalachicola National Forest, Tate’s Hell State Forest, and The Apalachicola Wildlife and Environmental Area. The Northwest Florida Water Management District manages two sites where you can hunt along the river: Florida River Island and Beaverdam. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has a hunting page on their website that’s full of resources and information.

What will the Apalachicola River look like in seven generations?

I was sitting here, editing this video, when I heard Jim say that his family had been in Calhoun County for seven generations. It reminded me of something in the EcoShakespeare show, which I had finished days earlier. Towards the end of that program, Madeleine Carr says that, in caring for Wakulla Springs, we must think seven generations ahead. She is invoking the Great Law of Peace, the constitution of the five nations of the Iroquois. Of the leaders of the five nations, referred to as mentors, it says “The thickness of their skin shall be seven spans — which is to say that they shall be proof against anger, offensive actions and criticism.” As it is often interpreted, the Great Law is asking that we think beyond whatever conflicts and pettiness would distract us in the moment, to think of future generations. You don’t have to squint too hard to see in it a message for the mentors of Florida, Alabama, and Georgia. To Madeleine, and many other environmentalists, it’s a message for all of us.

It’s interesting to think of seven generations of environmental stewardship when, for so many Floridians, our families have only been in the state for one or two “spans”. Our last EcoAdventure subject, Susan Cerulean (born in New Jersey), wrote about this in her 2005 book, Tracking Desire. In the chapter called Restorying, she laments not only our population’s lack of roots in our natural landscape, but the lack of old stories to connect us to the land. She had been looking for stories of swallow-tailed kites from Florida’s original inhabitants, but realized that any that might have existed were likely lost when the state’s native peoples were driven out or killed by Europeans. “With the genocide of the original peoples, we lost a profound opportunity to understand the landscape.”

Jim McCellan wrote his book in part to preserve a culture nourished by the Apalachicola River. It may not represent thousands of years of native wisdom, but it’s as deep as Florida roots go. Susan’s stories, on the other hand, combine research and personal stories. Research and experience; people differ on which carries more weight. Research can teach us quite a lot about the natural world; it’s what this blog was originally founded on. But there’s something to be said about the experience of Jim and his family, who can look back at this land for as many generations as the Great Law requires we look forward.