Dr. Randall Hughes FSU Coastal & Marine Lab

Most of my blog posts have revolved around my research in salt marsh habitats, with mention of seagrasses only in the context of their role as wrack in the salt marsh. However, I’m also interested specifically in seagrasses and the community of animals that they support, and particularly in understanding why seagrasses are experiencing declines in so many regions of the world. First, a little background on the plants themselves:

Most of my blog posts have revolved around my research in salt marsh habitats, with mention of seagrasses only in the context of their role as wrack in the salt marsh. However, I’m also interested specifically in seagrasses and the community of animals that they support, and particularly in understanding why seagrasses are experiencing declines in so many regions of the world. First, a little background on the plants themselves:

Seagrasses are land plants that evolved to thrive while living completely underwater, even producing flowers and water-borne pollen so that they can reproduce when submerged. There are approximately 60 species of seagrasses around the world, in both temperate and tropical habitats. Florida is home to around 6 of these species, with turtlegrass (Thalassia testudinum) the dominant species in our area.

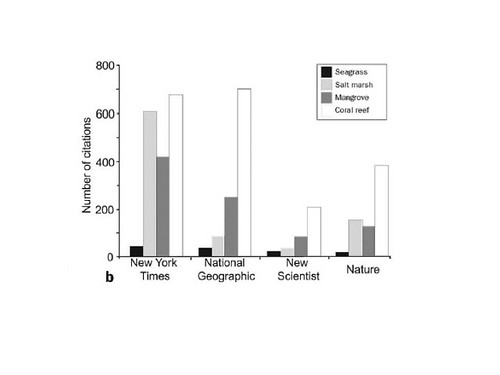

Public awareness of seagrass habitats and the threats they face generally lags far behind that of other marine habitats such as coral reefs (see figure) – have you ever heard them? However, seagrasses do lots of things for the environment that are valuable to humans. Seagrasses are extremely productive, surpassing even the productivity of fertilized corn fields, and some large seagrass beds are even visible from space. They absorb nutrients and sequester carbon, and they also provide vital habitat for a diverse group of marine animals. Approximately 85% of the commercial and recreational fishery species in Florida spend some portion of their life in seagrass beds!

Public awareness of seagrass habitats and the threats they face generally lags far behind that of other marine habitats such as coral reefs (see figure) – have you ever heard them? However, seagrasses do lots of things for the environment that are valuable to humans. Seagrasses are extremely productive, surpassing even the productivity of fertilized corn fields, and some large seagrass beds are even visible from space. They absorb nutrients and sequester carbon, and they also provide vital habitat for a diverse group of marine animals. Approximately 85% of the commercial and recreational fishery species in Florida spend some portion of their life in seagrass beds!

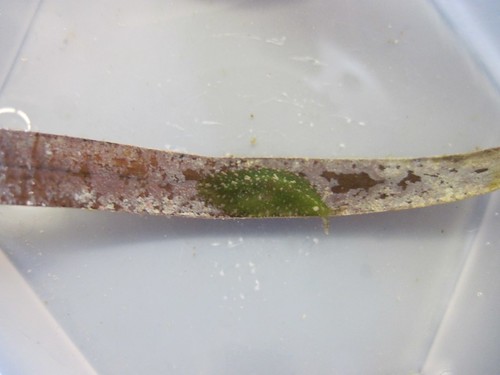

A recent analysis found that 58% of the world’s seagrass meadows are declining, and the rate of decline has increased in recent years. Lots of factors contribute to these declines, but two critical ones include coastal development and declining water quality. Often, seagrass declines are linked to an increase in the algae that naturally grows on the blades of the seagrass plants; known as epiphytes, these algae can out-compete and overgrow seagrasses in some situations, causing the seagrasses to die. Thus, it is important to understand the relationship between seagrasses and their epiphytes and the factors that control epiphyte abundance.

The Big Bend of Florida is home to one of the largest seagrass beds in North America. The remoteness of this region has thankfully limited impacts from coastal development, but it has also contributed to a paucity of ecological studies of these vast seagrass meadows. Working with Dr. Chris Stallings at FSUCML on a project funded by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, we have looking at epiphytes and Thalassia in the Big Bend of Florida. In addition to the epiphytes and seagrasses themselves, we are also interested in the abundance of key grazers (that tend to prefer consume the more easily digestible epiphytes, benefiting the seagrasses), the concentrations of nutrients in the water (that tend to benefit epiphytes), and clarity of the water (that determines whether seagrasses receive enough light to survive and grow). In the future, we plan to conduct field and laboratory experiments to look at the relative importance of nutrient levels and grazer abundances on epiphytes and their consequences for the health of seagrasses in this region of Florida.

A natural history tidbit –

We recently found several Phyllaplysia engeli individuals in the seagrass beds of St. Joe Bay. These small, cryptically-colored sea hares are known inhabitants of seagrass beds in this region, but not much is known about their ecological role. I studied a related species, Phyllaplysia taylori, in California seagrass beds; by grazing epiphytes, that species of Phyllaplysia had strong, positive effects on the seagrass Zostera marina. We are excited to see whether a similar relationship exists between this sea hare and its host seagrass, Thalassia. Plus these critters are really cool!

3 comments

Grand Lagoon in Panama City Beach is experiencing annual algae blooms that are apparently killing the turtle grass by blocking the sun. It has been very bad the past few years. The Lagoon turns into a slimy muck that makes me think primitive life will take over due to man’s polluting influence. I watched the Turtle grass expand dramatically over the past 20 years after the clay roads were paved and the water cleared. Now I am very sad that the beds are thinning, again dramatically. I’ve heard that fertilizers from lawns is the culprit. In the past 20 years all the vacant lots have been built upon with huge houses and grassy lawns. Won’t someone please push for standards requiring natural landscaping? Am I wrong about what has happened?

[…] as part of a new endeavor we are undertaking (stay tuned). In the meantime, I refer you back to Randall’s post on seagrass beds and epiphytic algae, and her post (with a video hosted by graduate student Emily […]

[…] Watch Emily survey seagrass beds and learn more about epiphytic algae. […]

Comments are closed.