On an overcast day in late February, I set off with my husband and our two dogs to hike the Bluffs of St. Teresa, a 7,700-acre tract of land recently acquired by the state park system. About an hour’s drive from Tallahassee, the Bluffs are located just past Ochlocknee Bay, right where the tip of Alligator Point snakes back towards Florida’s mainland. Right before we reached the turnoff for the trailhead, we drove over the massive bridge that crosses the bay—dark blue water sparkling beneath us.

The Bluffs are a tract of land that has been added to Bald Point State Park—a coastal state park with beaches and marsh trails. While the Bluffs are now part of Bald Point, to get between Bald Point’s beaches and the trails of the Bluffs requires a short drive. This tract of land, however, is an important addition to the natural lands south of Tallahassee. With this acquisition, Bald Point is now joined to Tate’s Hell State Forest, adding another connection to a wildlife corridor that also includes the Apalachicola National Forest, Ochlocknee River State Park, and the St. Marks Wildlife Refuge.

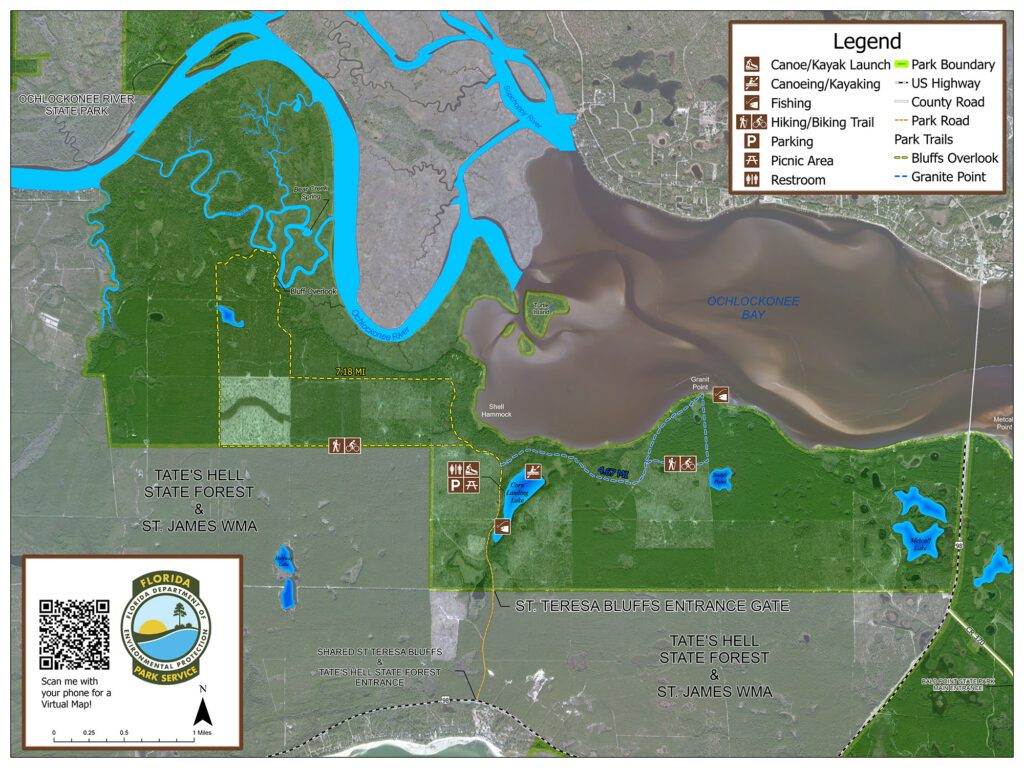

The area at the center of the map is the Bluffs of St. Teresa. To the north of it is Ochlockonee River State Park, to the east, Bald Point State Park, and to the south and west, Tate’s Hell State Forest.

Hiking the Bluffs of St. Teresa

Because they are a new land acquisition, the Bluffs are a bit off the beaten path. To get to the Bluffs from Tallahassee, you’ll turn off US-98 onto dirt roads that meander through Tate’s Hell’s pine forests, before being dumped at a little dirt parking lot. While the dirt roads in Tate’s Hell are rustic, I find that they are usually well enough maintained that you can take a sedan through them, and there are often road signs and markers guiding you through the forest, preventing you from getting as lost as Cebe Tate infamously did over a hundred years ago.

There are 20 miles of hiking trails in The Bluffs, and you have the option to bring your own boating/kayaking equipment (non-motorized) and explore Corn Lake. A short walk from the parking lot, Corn Lake is framed by picnic tables and tall grasses. With glassy water and nearly nobody around, it offers an opportunity to be truly alone on the water, without hearing motors or music.

I hiked the Bluffs Overlook Trail—a 7.5-mile loop trail that meanders, largely, through pine forests on wide forest roads. (Although I did brush a tick or two off me, the mostly wide roads help keep them further at bay.) I followed the trail via a geo-referenced map you can download from the State Park website that allows you to track your progress on the trail without internet, insuring you don’t get lost. I found, however, that the paths were wide and easy to follow.

The Ecology of the Trail

The Bluffs Overlook trail starts with a short incline through a forest punctuated with oak intrusion. Turkey oaks line a sandy trail imprinted with tire tracks. As the trail progresses, the oaks give way to land dominated by rows and rows of pines. Much of the land purchased for the Bluffs was former pine plantation land, something that became increasingly obvious as I wandered through skinny pines planted in distinct rows. Beneath the pines, a carpet of needles with a distinctly red tint coats the ground. Here, the pines have largely not yet matured, and years of human intervention/agriculture are obvious.

Not many wildflowers, grasses, or palms are growing beneath these pine trees. The bareness of the ground is indicative of the lacking biodiversity. Pine plantations typically have low biodiversity. This is caused by many factors: repeated harvesting disrupts the land and stops ecosystems from developing fully, herbicides and fertilizers are used on the land which disrupt the naturally processes, and genetically modified pines are planted closer together than they occur naturally, and they are planted neatly in rows. While, occasionally, I spotted a native understory plant, such as a clump of wiregrass, largely this land is devoid of the native species that make up a healthy pine ecosystem. The State Park plans to restore the ecosystem into a longleaf ecosystem over time, but the land was only recently acquired and this process is often a long one.

While there are many components to restoring a longleaf pine ecosystem, reintroducing fire to the ecosystem is one of the most important parts of restoration. Longleaf pine forests are fire-dependent. Fire helps to clear the understory of the forest, opening up the landscape to increased light. As longleaf pine saplings need ample light to mature, fire manufactures their ideal growing conditions. Other native species respond well to fire, including saw palmettos, which often reemerge quickly and with vigor after a burning. Recently, at Lake Talquin’s Bear Creek Educational Forest, I took the “talking tree trail”—a trail dotted with informative signs—and learned that early European settlers who used fire in an attempt to clear land for settlement were dismayed and confused that many plants, including saw palmettos, only seemed to grow stronger with frequent burns.

Appreciating Transition

Because the Bluffs are a landscape in transition—a landscape used for agricultural purposes that is being returned to a more “natural” state—I think more about the trail in terms of what is to come. Rather than focusing on the adventure of the hike, or the ecology of the trail, I’m more focused on what the acquisition of this land means for its future, and for the future of the Big Bend.

This, however, doesn’t mean that the trail is “boring” or not worth visiting. Much of the trail is layered with shade, making for a pleasant walk, and at the time I walked the trail, the landscape was drenched in color. The fallen pine needles that coated the ground were a rich maroon color, and between the rows of pines, puffy chunks of teal reindeer lichen coated the ground.

The sheer amount of reindeer lichen on the trail was starkly beautiful. This species typically needs very bare and exposed soil to grow, meaning that it does not grow in large quantities in a well-maintained longleaf ecosystem, which often has a dense understory (and very little midstory). However, I still enjoyed seeing it coating the ground. I also enjoyed seeing a forest in transition. As I walked the Bluffs Overlook Trail, I began to imagine what the restoration process of the Bluffs looks like. So often we see landscapes in extremes—protected or developed. Getting to see a landscape in transition and having the opportunity to revisit the landscape as the State Park System continues to revitalize it provides a unique opportunity to appreciate the dedication it takes to restore landscapes. People who restore longleaf habitats tend to view them as projects hundreds of years in the making, and so, if we continue to follow the transition of these bluffs, we will be able to see the earliest stages of habitat restoration.

The View from the Bluffs

After 3 or so miles, the Bluffs Overlook Trail begins to climb, slightly. As the elevation changed, the ecosystem changed as well, becoming scrubbier. The nearer I got to the Bluffs, the more my feet began to sink into thick sand. Dune-like ridges began to rise around the trail. Plants around me began to look drier and more brittle. Small oaks began to line the trail, indicating water was near. Oaks and other hardwoods become more plentiful as pine ecosystems meet water. This is because water stops or slows down fire. The absence of fire allows hardwoods, which are normally knocked back to their roots during burns, a chance to mature. Pines, unlike hardwoods, are more resilient against flames and actually thrive in a ecosystem that is burned.

The fact that this trail builds towards a designated viewpoint made it feel unique. I moved to Florida from northern Virginia. In the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, my hikes typically culminated in views of the bucolic Shenandoah Valley. In Florida, however, I feel that terminating in a viewpoint is rarer. Rather, I find that when I hike in some of my favorite places—like St. Marks Wildlife Refuge, along Alligator Point, or at Piney-Z Lake—I enjoy views along the way, rather than at a designated viewpoint, often of water and wading birds.

The Bluffs Overlook is an excellent place to stop and enjoy a picnic or a snack. Here, as the trail reaches its highest point, a wooden fence separates the Bluffs from the marsh. Nearby, a picnic table provides a great place to stop and rest. Past the fence, extensive marshland sprawls outwards. Spindly wind-blown oaks interrupt a view of sparkling water and spartina grass, and in the distance, you can spot the expansive bridge that spans the Ochlockonee Bay. The view is spectacular. From the Bluffs, you are elevated about the water below and provided a perspective that is unique in this very flat state.

As the trail makes its way to and from this viewpoint, you can sneak further views of the marsh and the Ochlocknee River. While often obscured by vegetation, occasionally, the brush will peel away, revealing beautiful sightlines of wetlands.

The Benefits of Interconnected Natural Lands

Knitting parcels of protected land together to create larger contiguous plots of land is something that is becoming increasingly trendy in conservation. In June of 2021, lawmakers in Florida passed the Florida Wildlife Corridor Act, setting aside $400 million for connecting natural areas within the state—an endeavor supported by the Florida Wildlife Corridor Foundation: a nonprofit that aims to strengthen the Florida Wildlife Corridor. The Florida Wildlife Corridor Foundation has a fun map you can click around on that shows not only the land that has been set aside, but also the way you can use this land for recreation—camping, hiking, paddling, etc.

Interlinking natural areas together instead of simply setting apart individual forests, beaches, rivers, marshes, or other types of land is important for many reasons. Animals really benefit from interconnected land as it extends their ranges. Whereas if a state forest, for example, is set aside with no other land surrounding it, animals can become isolated on this land as if it were an island. If they feel compelled to leave—to find more food, to find their own territory, or to find another animal to mate with—they risk losing their life crossing a busy road, or finding themselves in an inhospitable place, such as a neighborhood or city. Of course, roads still pass through connected and preserved lands, but with less development, these risks are lessened.

Many animals migrate or establish their own territories, and having interconnected natural areas allows for them to expand their ranges to do these things. Research has demonstrated the way species such as the Florida Panther (endangered) and the Florida Scrub-Jay (vulnerable), have struggled because their territories have been reduced. Recently, I visited the Tallahassee Museum and wrote about the way Florida Panthers have benefited from interconnected land. There is also a great documentary about the panther that illustrates how vast swaths of land are important for this charismatic large cat.

So many other species, such as the Florida Scrub Jay, benefit from large contiguous landscapes. The Florida Scrub Jay, Florida’s only endemic bird, is a small animal, and as it can fly, you might think it is less constricted by habitat fragmentation. However, in his book, Florida Scrub-Jay: Field Notes on a Vanishing Bird, Mark Jerome Walters writes about how habitat loss and fragmentation aresome of the main reasons that Scrub Jay is suffering. As their name would suggest, Scrub Jays exclusively live in scrub, an arid, low-nutrient ecosystem dominated by shrubs and dwarf oaks. Scrub is hot and unforgiving. It is not one of Florida’s most beautiful and well-loved ecosystems. Because of that, much of our native scrubland has been developed into commercial and residential real estate or orange groves. So little remains that many Scrub Jays are isolated in pockets of land and are unable to find birds not within their family units to mate with. In a desperate attempt to save the species, scientists have resorted to driving Scrub Jays between territories to allow them to mate with one another—a solution that is ultimately unsustainable. Clearly, we need a more permanent solution.

There are many other ways that interconnected landscapes are beneficial. Other ecological features, such as waterways (rivers, bays, oceans) are cleaner when surrounded by more natural land. One of the major ways bodies of water are polluted is through run-off, wherein water that has been polluted, often by agriculture or other human activities, makes its way to water sources without being cleaned. When water travels through wetlands and soil, it undergoes a natural cleaning process before it is reabsorbed in the water table. By protecting larger swaths of land, we sustain more of the earth’s natural cleaning processes and ensure that our waters are less polluted.

Further, acquiring more land along the coast provides us better protection against tropical storms and hurricanes. Natural ecosystems, especially wetlands that naturally ebb and flow, absorb and slow down storm surge, which can be the most dangerous and destructive part of a storm. In one of our recent posts, Rob wrote more about the way natural ecosystems can disrupt the motion of water much more effectively than manmade protections and about how here in the Big Bend, we are more protected because we have more natural areas abutting the coast than other areas in Florida.

Another surprising downfall of habitat fragmentation is that it helps combat tick-borne illnesses. I recently hiked the Aucilla Sinks section of the Florida Trail, and while I was astounded by the natural beauty of the trail (it was perhaps, the most beautiful and interesting trail I’ve hiked in north Florida), my dogs and I picked up dozens of ticks on the trail. What was it about that trail that made it harbor so many ticks? I wondered, as I sat on the back porch with my dog and a pair of tweezers, plucking the arachnids buried in his fur. Evidentially, the less diverse a landscape is, the more likely it is that said landscape will harbor more ticks and tick-borne illnesses. As smaller tracks of land and tracks of land that are interspersed with suburbs, cities, farmland, and timber plantations have less biodiversity than larger tracts of wild land, these areas become meccas for ticks and tick-borne illnesses. The Aucilla Sinks section of the Florida Trail winds through both natural and managed land and passes through many different ecotones. In other words, it’s the perfect environment for ticks and tick-borne illnesses. The fact that fragmented land can cause something as unexpected as increased tick-borne illnesses really speaks to all the many unexpected and unknown benefits of protecting large tracks of land.

The End of the Trail and What’s to Come

I was not able to finish my walk along the Bluffs Overlook Trail, an end to my day that seems fitting. The Bluffs themselves are an ecosystem that are far from finished; the State Park has a great deal of work to do to restore the landscape and to finish making it the dynamic puzzle piece that it promises to be. As I followed the loop back to the parking lot, I was thwarted by a waterlogged trail. A nearby bog had overflowed and expanded its reach, soaking the trail and forcing my husband, my dogs and I to return on the path from where we came. While it was disappointing, our forced turn-around did afford us another view of the stunning Bluffs for which we came.

As I hiked in the dry season, I imagine that the flooding I experienced is fairly common. I’m also hopeful that as more attention is paid to this tract of land, a boardwalk will one day take hikers across this boggy area. Maybe by that time, the bogginess will be more reminiscent of native Florida wetlands. Perhaps one day there will be pitcher plants blooming along the trail. Maybe gators will take up residence within the inland lakes (maybe they are already there). Ultimately, what makes me most excited about my day at the Bluffs is imagining what is to come and knowing that this land will work in tandem with the other stunning, diverse landscapes that carpet the Big Bend.