The following is a post by Florida State University PhD student Liesel Hamilton. The photos featured come largely from Wakulla Springs Alliance volunteers Doug Alderson and Bob Thompson, spanning decades of Wakulla Springs wildlife surveys. Photos from the day of our wildlife survey were taken by WFSU Ecology Producer Rob Diaz de Villegas.

Bundled up in down, I stood on the dock at Wakulla Springs State Park on a cold December morning waiting for the wildlife survey boat to depart. A heavy mist hung over the spring’s iconic blue-green water as pied-billed grebes and hooded mergansers disappeared in and out of the fog, their gray and brown feathers rendering them dark silhouettes. Spanish moss hung loosely from the cypress trees emerging from the center of the river, their epiphytic strands adding more gray to the already strikingly monochromatic landscape.

That morning, I would join volunteers from the Wakulla Springs Alliance as they performed their weekly survey. Their boat, a small pontoon devoid of any seating, would depart the dock at 9am–an hour before the first Jungle Cruise Tour is scheduled to take visitors down the spring, searching for alligators and anhingas and herons. I had arrived early, lingering around the dock as Bob Thompson and Doug Alderson–the volunteers for the morning’s survey–disappeared in and out of a nearby shed, acquiring clipboards and pens and liability forms for Rob Diaz de Villegas and myself to sign.

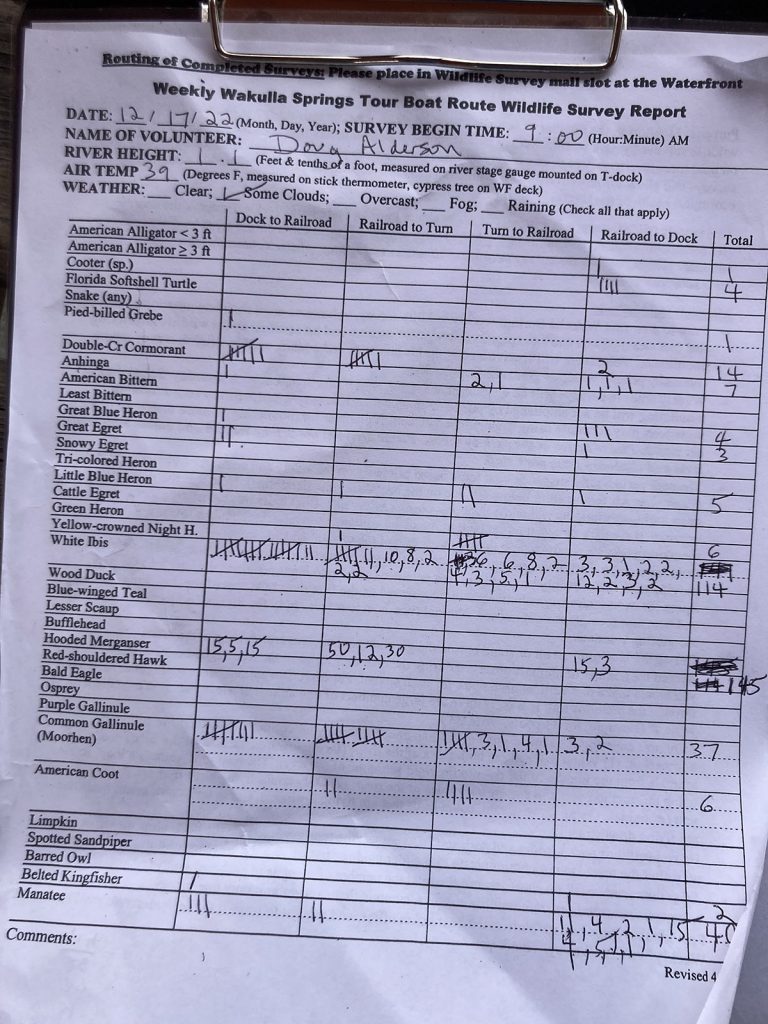

As we waited for 9am to arrive, Doug secured a blank survey sheet outlining the thirty-four species that the alliance tracked to a wooden clipboard. At the top of the sheet he filled in his name, the height of the river–1.1 feet–the weather–some clouds–and the current temperature–39 degrees. While common gallinules and manatees floated near the dock, Doug wouldn’t start tallying them until we left the dock, promptly at 9am.

Since 1992, a team of volunteers associated with the Wakulla Springs Alliance has conducted a weekly wildlife survey at Wakulla Springs–the extensive analysis of that data can be found here. Most often, the survey is done by two volunteers, a driver and a wildlife surveyor, who record data on the number of species spotted on the tour boat’s typical route–up the spring about a mile, and back through a narrow canal, circling the spring basin before returning to dock. Prior to 1992, a survey was conducted monthly, but volunteers began to recognize how much variability could exist in data that was collected so infrequently and how much easier it was to analyze trends in more consistent data. I could see how these anomalies might look even just going out once with the wildlife monitoring crew. On the cold December morning that our boat cut through the fog, our crew only saw one alligator–a large leathery specimen whose wide girth suggested he had recently enjoyed a meal–but on a warmer winter morning, not to mention a summer morning, we easily could have seen dozens of Wakulla’s beloved scaly reptiles. In fact, a week or so later, my family and I chugged down the river on the 12:30 Jungle Cruise tour and spotted more than 50 gators–some massive specimens sunning themselves on banks, some swimming alongside our boat, and many babies, tangled up together amidst thick clumps of vegetation, no doubt under the surveillance of a nearby protective mama.

While alligators were in short supply that morning, many animals were out in droves. As I wandered back and forth across the front of our small, silver pontoon boat, Doug, clipboard in hand, counted the 114 white ibis perched in cypress trees or using their curved orange beaks to probe the mud for crustaceans. From a top of a needle-less cypress, an osprey surveyed the water for fish.

Little blue herons crossed back and forth in front of our boat, and mullet jumped downstream, hurling their bodies across the water, disrupting its glassy surface. One of the four Great Blue Herons we would see, disturbed by our presence, glided across the river, nestling itself along the shoreline, its guttural screech punctuating the still morning air, interrupting the chuckling of the moorhens as they bobbed near the river’s vegetative islands.

The most common animal that morning, however, were the hooded mergansers, a black and white duck that overwinters in warmer places like Florida, common, even in drainage ditches and lakes within Tallahassee. As they are diving ducks, searching beneath the water for tadpoles, crayfish, and crabs, mergansers sit low to the water, and often can be seen in pairs, or even huge flocks. The feathers of the females are mostly shades of brown and white, while the brown underbellies of the males contrast against their black and white feathers, striped in intricate patterns across the birds’ chests and backs. Their most striking feature, the feature that gives them their name, are the pointy “hoods” of white and black feathers that seem to grow from the top of their heads–the flatness of these hoods giving off the appearance that the birds’ heads were smashed beneath two very heavy books.

That morning, Doug counted 145 hooded mergansers. Many of them congregated in massive flocks beyond where any motorized boat is allowed. The state park system owns the first three miles of the Wakulla River, from the 185-foot deep spring bowl to a chain-link fence that straddles the river, low enough to keep kayaks, canoes, and other boats out of Wakulla Springs, but high enough that manatees and alligators can slip under its slats. In the 1970s, Edward Ball, the former head of the St. Joe Paper Company who owned the land before the state park, slapped the chain link fence across the Wakulla River in order to keep the “riff raff” out of the preserve wherein he built an elaborate lodge that now serves as a hotel operated by the State Park System. When Ball built the chain link fence it was controversial as it is illegal to close off access to a navigable river. Rumors circulated that Ball, with his strong influence and vast fortunes, bought off the judge who approved his barricade.

As Doug leaned downstream, his finger dancing through the air as he counted mergansers disappearing into the fog, he told me that the animals in this part of the river are more skittish than the ones that usually hang out in the first mile of the river–the alligators, the cormorants, the herons that nest and feed in the first mile have grown accustomed to the tour boats constantly chugging along the river. Beyond where the tour boat turns around, the animals only see humans twice a year, when a survey crew conducts an animal count on a series of canoes that wade through the only section of navigable river left in Florida that is truly wild.

We lingered for several minutes staring downstream, counting birds, before Bob cranked the engine back into gear and our boat turned down a narrow corridor to take us through the canal that would lead us back to the dock. On our right, we kept our eyes peeled for yellow crowned night herons, which often nest on the island where the boat turns around, so accustomed to the boats, they’ll build their nests so close that visitors can sometimes peer into them, watching a bird incubate her bluish-green eggs in the spring, or even, chicks stretching their necks upward during the summer months, hoping for a taste of regurgitated crayfish. Doug counted 6, a good number for one of the rarer herons to spot on the river.

“I always thought it was funny,” Bob said. “When I’d lead a boat tour and I would try to point out this bird that’s really rare for the river and everyone would rush to the other side of the boat, to see another alligator.”

While he now drives volunteers up and down the river, Bob used to work at Wakulla as a ranger. Despite being retired, he doesn’t want to relinquish his time on the river.

“Usually my favorite day is when I’m on the river,” Bob told me, when I asked him for his best moments, of the hundreds of times he’s boated up and down the river. “It’s awesome. The place inspires me, you know?”

Bob stalled the boat again so we could watch a night heron perched on a cypress limb. Long yellow feathers dangled off the back of the bird’s bright yellow crown–the line of yellow feathers that traces the bird’s head, from front to back, contrasting the inky black feathers surrounding its face, its bright orange eyes.

When we neared a bend where vultures congregate in mass, we searched for limpkin. Limpkin, a tawny shorebird with a long, curved beak, perfectly adapted for sucking apple snails from the shells, disappeared from Wakulla Springs for nearly a decade after the springs became uninhabitable for their main food source, the apple snail. Now, the birds have reappeared, hanging out in the corridor that was made famous by Tarzan’s piercing yodel. I saw a pair on a recent boat trip, but that morning, there were no limpkins to be found. Instead, we saw more coots, another migratory bird, as well as dozens of black and turkey vultures, although these birds were not part of Doug’s count as the Alliance only counts birds that are dependent on the river for survival–vultures merely use the river as a roost.

As our boat veered out towards the spring, our eyes focused on the water, searching for the manatees gliding alongside our vessel, their oblong gray bodies blending into the blue-green spring water below. On a cold day like ours, manatees will congregate mainly near the headwaters of the spring, the large circular basin that sits adjacent to the park’s diving tower, where the water comes out seventy-two degrees–far warmer than most river water in the winter. As we circled the spring, Doug tallied furiously. A manatee mating pod churned up the water several feet away, pods congregated in the roped off swimming area, a mother and calf exhaled loudly as their snouts surfaced about the misty water–a breath of air that allowed them to submerge themselves once more. By the time we finished the tour, Doug had counted 40 manatees, a sizable number for Wakulla Springs.

How manatees are doing at Wakulla Springs- by the numbers

While I’ve grown accustomed to bad news surrounding manatee survival as they continue to struggle amidst Atlantic algae blooms and collisions with boat propellers, at Wakulla, the Manatee population has recently showed healthy numbers. On a wildlife survey on November 19th, a few weeks before my own survey, volunteers counted 56 manatees, the most manatees counted since the park started counting them in 2003. These numbers are complicated, however, as overall, the manatee population has been volatile, especially because of an outbreak of nonnative hydrilla that plagued the park from 1997-2012.

Hydrilla is an invasive aquarium plant that creates thick mattes on the top of water. Rangers tried to control hydrilla, which was first observed near the boat dock in April 1997, with herbicides–a tactic that would temporarily eliminate the plant, but wouldn’t stop it from growing back, the treatment plan relying on an endless cycle of pesticide use. The solution depended on the city of Tallahassee updating their wastewater treatment plan, which reduced the amount of nitrate-nitrogen that ended up in the spring. This coupled with increased manatee activity in the spring, helped control this invasive species. Manatees will eat hydrilla, lots of it, as part of their herbaceous diet. The increase of manatees grazing in the spring, which began during 2012, was not only a joyous event for wildlife viewers, it also greatly helped reduce the invasive hydrilla that plagued rangers for years. Manatee presence in the spring peaked between 2012-2014 as they took advantage of this food source. Since then manatee populations have been decreasing, but the 56 manatees spotted by survey volunteers is cause for celebration.

How does hydrilla affect wildlife at Wakulla Springs?

The hydrilla’s colonization of the Wakulla Spring makes the Alliance’s overall data complicated to analyze. In the Upper Wakulla River Wildlife Abundance Trends Report, the data and the analysis of whether the 24 species analyzed (primarily birds, but also including American alligators and Manatees) are decreasing in number, increasing in number, or demonstrating no significant trend is broken up into periods determined by “Long-Term Counts per Survey (1992-2000), Hydrilla Invasion Counts per survey (1992-2000), Hydrilla Management Counts per Survey (2000-2012), Post-Hydrilla Management Counts per Survey (2012-2021), and Current Apparent Status” (page 13). Seasonality is also accounted for in this data as many of the spring’s residents breed in or migrate to the winter during specific seasons. Manatees, for example, are much more common in the winter as they depend on warm spring water during colder months, or American coots, are a migratory species that spends its winters in the springs. The data is broken up into these categories because the massive amount of hydrilla in the spring essentially shifted the entire food web. Hydrilla is a food source for animals that eat aquatic vegetation, such as American coots and common gallinules, and so, the presence of hydrilla in the spring unnaturally inflated their numbers.

The data has also shown the river is shifting in terms of food sources offered (post-hydrilla control). Animals that rely predominantly on submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) as a food source, including common gallinules, American coots, and manatees, are declining, by and large, whereas animals that favor a more detrital-based food web (crayfish are a big part of this food web as they feed on detritus), such as hooded mergansers, yellow-crowned night herons, and juvenile alligators, are increasing. Additionally, animals that feed on medium or large sized fish are struggling. This includes osprey, great blue herons, and anhingas. Other changes in the river, such as periodic salinity spikes, will further determine what animals can best make a home on the Wakulla.

Water quality and clarity- and its changing movement below ground

The water quality also varies extensively from week to week, month to month, year to year. A separate team of volunteers monitors the water quality weekly–one of the many teams collecting data about Wakulla Springs. One of the things they have observed is large quantities of chlorophyll in the water, a byproduct of decomposing plant life, as well as an relative absence of tannins that give blackwater rivers their distinct coloring. Because of this, the water at Wakulla has developed a distinctly green color.

One of the big goals of the state park is for the water clarity to improve enough for them to once again run the glass bottom boats that have been docked for years. Our understanding of why the water quality varies or how to fix it is constantly evolving, as we learn more and more about the Florida aquifer. The Wakulla Springs Alliance recently published a comprehensive report on the springs water quality. Additionally, a recent study discovered an enormous underground river that connects Tallahassee to Wakulla. Another recent FSU study has analyzed the connection between the industrial extraction of spring water, which pushes tanin or chlorophyll stained water into the spring, and the decreased clarity of the spring. This is exacerbated by rising sea levels, which can filter brown or green water back into the spring system, instead of allowing it to be expelled into the ocean via its normal process. During this process, spring outflow can additionally become backed up, which further increases the amount of non-clear water that filters into the spring.

A full understanding of how we can protect the spring, including its species and the natural beauty of its water, will be contingent on more data from the Wakulla Springs Alliance. Much of their recent comprehensive report calls for just that. As the data gathered is relatively new, and as the spring was recently disrupted by hydrilla, which completely altered its food web, it can be difficult to understand the trends that we are observing. Only time and more information will help.

A few favorite photos from Bob and Doug