See the insane pollinator action on devil’s walkingstick flowers in this short video. If you’re on a computer, try watching in fullscreen mode to see just how many insects are buzzing around. Thank you to the Lammers family for letting us in to your yard to film.

There are any number of reasons that a plant gets a bad reputation. It could be harmful in some way, sporting thorns, bristles, or toxins. Maybe it’s too “weird looking” to fit in with your landscaping look. And we don’t always appreciate plants that spread where we don’t want them. Depending on your gardening preferences and personal aesthetics, devil’s walkingstick might meet each of these criteria.

And yet, if you have space to let it grow, it might become your new favorite pollinator plant.

Earlier this year, I wrote about embracing weeds in your yard. Yes, it’s satisfying when bees and butterflies swarm those coneflowers I bought. But it’s equally pleasing when I see bees hopping between Ohio spiderwort flowers in a patch of yard I haven’t mown in a while.

Ohio spiderwort isn’t the same as devil’s walking stick. Aralia spinosa can grow to twenty feet tall and spreads itself through underground rhizomes. Left unchecked, you could find yourself with a small thorny-trunked forest. But one that, for a few weeks in July, will attract dozens of pollinator species.

In this post, we’ll look at how this plant grows, and how you might manage it if you decide to include it in your Florida friendly landscape. We’ll also take a look at the many, many species of pollinator I caught on video in a single yard. If, like me, you love watching pollinators on flowers, devil’s walking stick is mesmerizing.

Aralia spinosa at a glance

- Common names: devil’s walkingstick, angelica tree, Hercules club, prickly elder, prickly ash

- Height: between 10 and 20 feet

- Spread: between 6 and 10 feet

- Full sun to part shade

- Drought tolerant

- Easily grown from seed or transplanted. Spreads by rhizomes and seeds dispersed by birds.

Devil’s Walking Stick- Flowers That Make Pollinators “Drunk”

The yard I’m visiting belongs to Jonathan Lammers. The historian first appeared on the Ecology Blog in our two-part look at live oaks in Tallahassee; he’s kind of a plant guy. You can see this in his yard- clusters of planted coneflowers and rosinweed, and a large patch of woodland sunflower along the fence. Coming up the driveway, I see the dotted horsemint has gotten tall and leafy, ready to bloom later this summer.

The yard is full of plants purchased to feed pollinators. At this time of year, though- I’m visiting in early July- the hub of pollinator activity is a row of small trees crowned with clouds of white flowers. I zoom a lens in, and it looks like someone is fast forwarding my video even as I shoot it. Some of the slower moving bumblebees and larger wasps I can identify right away. Other IDs will have to wait until I can get the footage home and pause it.

They’re so into the flowers, they don’t mind a nosy human looking in on them. “It seems the insects are so fixated on getting onto that flower,” Lammers says, “you can stand with your nose eight inches away. And they don’t care. They’re getting drunk!”

He first noticed full grown devil’s walking stick the summer after he and his family moved into this house a few years ago. Not knowing what it was, he looked it up. He then allowed it to spread, though he cut back or relocated saplings to keep a straight line parallel with his fence.

Identifying Devil’s Walking Stick When It’s Small

Before we get into its spreading habits, lets talk about those first baby devil’s walking stick sprouts you might see in your yard. After all, a twenty foot tree won’t just appear in your yard, so it’s helpful to first identify it as a youngling.

Just a few feet from the full grown trees, we see smaller devil’s walking sticks. Here on the Lammers’ lawn, the plant is spreading by rhizomes underground, creating a colony.

Devil’s walkingstick also grows from seeds dispersed by birds. It likes disturbed soil. Last fall, in a steephead ravine where Hurricane Michael had knocked down some trees, Florida Native Plant Society’s Lilly Anderson-Messec expected devil’s walking stick would be one of the plants to take hold in the new open spaces. And in Elinor Klapp-Phipps Park, the plant has formed colonies along the power line cut and by trails. These are manmade edges, places where humans created a disturbance by removing trees.

Now let’s take a closer look at the leaf pattern:

The leaves are what is known as bipinnatley or tripinnately compound. Huh? What does that even mean? The leaves, as we see in the photo above, grow on both sides of the same stem, in a mirror image. This is pinnately compound. Then, the stems themselves grow out in a mirror image from a central stem. Bipinnate. Many of the stems also have a single leaf at the end.

A few plants in our area have a similar leaf structure. Another thing that sets Aralia spinosa apart is that the overall shape of the leaves is a triangle. And, if you look closely, there are already small thorns on the stem.

Controlling- or Encouraging- the Spread of Devil’s Walking Stick

“Devil’s walking stick is well named in one regard, in that it will walk,” says Jonathan Lammers. The plants sends out rhizomes- underground stems, “so it has this nice habit of putting up shoots every three to five feet… When I started it was down towards the fence behind me. Now I’ve got a line that stretches thirty five feet. And that only took me five years to do.”

So it spreads fast.

It’s a plant to consider if you have some space to let it spread. If you stay on top of it, devil’s walking stick may work in a moderately sized space as well. They top out at about twenty feet, and about ten feet wide.

Lammers has had success taking saplings from the colony and transplanting to other parts of his yard. According to the Missouri Botanical garden, it will grow in average to moderately moist, well drained soils, but will tolerate drought. It likes full sun to part shade, though its preference is alongside larger trees. And it grows easily from seed.

In the Tallahassee area, the plant blooms in July, lasting for a few weeks. It has a broad range though, so somewhere else it might bloom as early as June and as late as September.

When it’s done flowering, birds and other animals eat its small fruit.

What Pollinators Visit Devil’s Walking Stick?

This is the good stuff. We see bees, butterflies, wasps, beetles, flies, and ants on these flowers. What I’ll do next is identify the insects we see in the video. After that, I’ll take a closer look at several others I photographed. And then, in a following section, I’ll include some photos of butterflies on Devil’s walkingstick in Klapp-Phipps Park from last year.

What pollinators do we see in the video?

I’ll limit this section mostly to insects we see close up. When watching the video, you’ll notice a large number of much smaller insects zipping around the animals I spotlight. Many of these are small flies. But, when you look at the slow motion shots at the end, you can see that some of these have yellow flecks on them. These are pollen sacs, on small Dialictus sweat bees.

00:00

We start with a couple of establishing shots, to show the intensity of action and diversity of pollinators.

00:18

During the shot, another honeybee tries to get onto that flower cluster, but the first one holds its own. You’ll see this type of interaction repeated in the video- one pollinator flies onto where one or more are already taking nectar. Either the intruder forces the first pollinators off, or those first pollinators stand their ground.

You may notice that the second honeybee has a more orange coloring, while the one in the photo is more grey, and with less pronounced abdominal stripes. This is a normal variation in appearance for honeybees.

The wasp in that shot is a humped-back beewolf, a wasp that hunts bees. A honeybee looks like it would be able to handle itself against the beewolf, but I could see it snagging one of the smaller sweat bees.

00:23

We have a page on local bees on the WFSU Ecology Blog. Carpenters and bumblebees are big and conspicuous, and easily recognizable to most people as bees. But if you take a closer look at your flowers, you’ll see bees of all shapes, sizes, and colors.

00:33

They circled the flower cluster for moment before they clashed- the metric paper wasp held its ground. While not inclined to bother with humans, metric paper wasps can be fierce when it comes to other insects. If you watch the video I’m linking here, you’ll see one skin a black swallowtail caterpillar. Here’s a closer look at both wasps:

00:39

Large solitary wasps are generally non-aggressive to humans. But I wouldn’t want to tangle with it if I were an insect pollinating this plant.

00:43

Later in the video, we see the male of the species in a wider shot. In my yard, we see females throughout the summer, and in August we have an explosion of males and females. Here we see a male in early July.

00:47

This and another species of beetle, the delta flower scarab, were mating all over the devil’s walkingstick. The delta flower scarabs weren’t in the video, but I did get a photo:

01:02

At the end of the video, we have a couple of slow motion shots, which show insect movement more clearly.

Butterflies on Devil’s Walkingstick

We didn’t see any butterflies in the video, though there were a few. These were mostly smaller butterflies- skippers, duskywings, and hairstreaks. There was also, briefly, this one:

Tiger swallowtail (Papilio glaucus)

Now why wasn’t this beauty in the video? It landed on the flower, took nectar for a second or two, and flew right off. It inspected another devil’s walkingstick or two, and then continued across the yard.

Last year, when I took a few visits to Klapp-Phipps to shoot pollinator video, I noticed something about large butterflies and devil’s walkingstick. They avoided the busiest flower clusters, preferring those with more spent flowers. In one shot, I noticed a bee bouncing off a tiger swallowtail’s wing; on the busier clusters, a large butterfly would take a beating.

The flowers on this plant had freshly bloomed, so the swallowtail could return when it’s less painful for it to pollinate this plant.

Silver-spotted skipper (Epargyreus clarus)

Horace’s duskywing (Erynnis horatius)

Red-banded hairstreak (Calycopis cecrops)

Not my favorite shot of a butterfly, but it was hard to get a good angle on this tiny butterfly on a high up flower. This butterfly’s caterpillars host not on a living plant, but on leaf litter. This is one of many insect species that need leaves on the ground over winter. Others include bumblebees and fireflies. Don’t we like these insects? Enough, maybe, to let some leaves lie in the winter?

More Bees and Wasps Spotted on the Devil’s Walkingstick

Blue-black spider wasp (genus Anoplius)

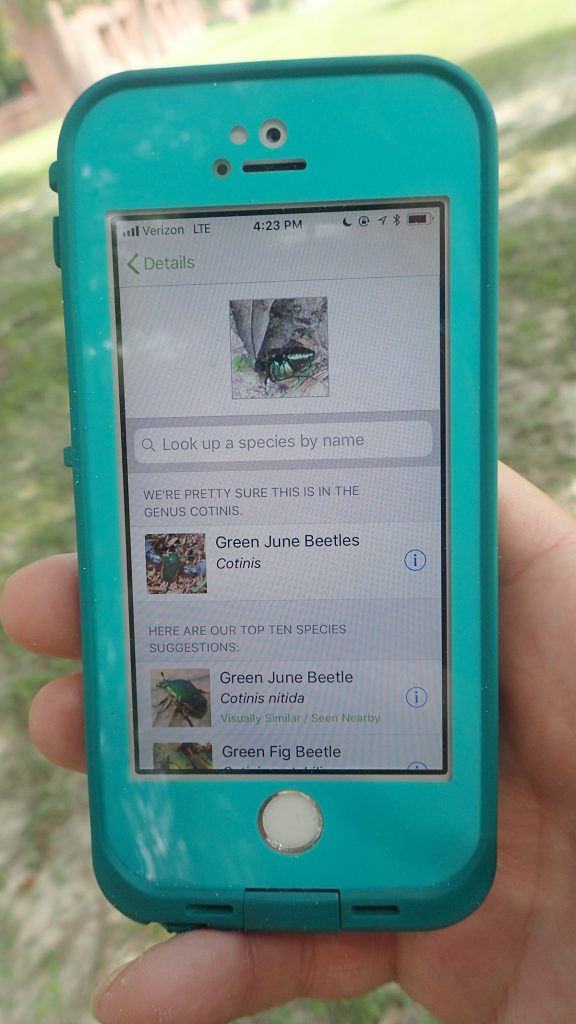

When I took my photos into iNaturalist to get IDs, I ended up with three different species of spider wasp. This one is only a genus-level identification.

Rusty spider wasp (Tachypompilus ferrugineus)

Entypus unifasciatu, a tarantula-hawk wasp

Tarantula-hawk wasps are a tribe in the spider wasp family.

Subtribe Crabronina (squareheaded wasps)

Here’s a second look:

Four-banded stink bug wasp (Bicyrtes quadrifasciatus)

One day I saw a stinkbug on a flower in my yard. The next day, I saw this wasp on the same flower. The four-banded stink bug wasp hunts and eats this garden pest.

Four-toothed mason wasp (Monobia quadridens)

Feather legged scoliid wasp (Dielis plumipes)

Here’s another look at the feather-legged scoliid, with fire ants. I’ve seen ants grab smaller bees before, and I saw a tarantula-hawk wasp grab an ant on this plant.

Leafcutter bee (Megachile genus)

I cropped this from a larger video image, so pardon its fuzziness. Devil’s walkingstick in bloom is a free for all of dozens of pollinator species. Some were easier to follow and shoot closer up, while other I noticed come in and out of the frame in less than two seconds. And many of them barely stopped moving at all. For every species I could make out, how many more were there?

Fly species on Devil’s Walkingstick

Trichopoda lanipes, a bristle fly

Bristle flies are a type of Tachinid fly, which are mostly parasitoid breeders. Here’s another look at this neat looking fly:

Another bristle fly species?

This is another video frame cropped down to center on this fly that popped in and out of a few shots. iNaturalist’s first guess is a bristle fly. I have to imagine there were also a few fly species represented in those little black blurs whirring about the flowers.

Bonus: Elinor Klapp-Phipps Park Devil’s Walkingstick Butterflies

I counted about twenty four species of insect on the Lammers’ devil’s walkingsticks. Those are just the insects I could make out looking up at flowers a few feet over my head, with many of the insects barely stopping and/or that were tiny.

I wanted to include a few more images from last year’s shoots in Klapp-Phipps Park. I have a taller tripod and the ability to zoom further in this year, so last year I didn’t have as many closeups of the smaller bees and wasps. But there were some cool butterflies.

Golden banded skipper (Autochton cellus)

This butterfly is rare east of the Mississippi, and is listed as imperiled in Florida. But Elinor Klapp-Phipps is a golden-banded skipper preserve, well stocked with the its larval food, the thicket bean. Where other butterflies like full sun, these prefer being out in the early morning. I filmed this one later in the morning, when they’d abandoned the sunnier power line cut area. This devil’s walkingstick was growing next to a shaded trail, where I found two or three golden-banded skippers.

This one left the flower and perched on a nearby leaf.

Tiger swallowtail (Papilio glaucus)

I know we already saw a tiger swallowtail on Jonathan Lammers’ devil’s walkingstick flowers, but at Klapp-Phipps, the butterflies stayed to nectar a while on the plants. This plant had less blooms than others nearby, where bees and wasps were going crazy.

Also, I saw this swallowtail:

Other swallowtails with black wings usually have multiple rows of colored spots. This one had me stumped. But, it turns out this is a black morph of the tiger swallowtail.

Red-spotted purple (Limenitis arthemis)

Dig Deeper into Backyard Ecology

What can we do to invite butterflies, birds, and other wildlife into our yards? And what about the flora and fauna that makes its way into our yards; the weeds, insects, and other critters that create the home ecosystem? WFSU Ecology Blog takes a closer look.

Apps and Citizen Science mentioned in the Backyard Blog

iNaturalist

Identify plants, animals, lichens, and fungi in your yard. Other users correct your identifications if you’re wrong, and even if they don’t, it can be a good springboard to further research.

Seek by iNaturalist

Instant identification, and it doesn’t record your location. This is a good option for kids with phones.

Monarch Larva Monitoring Project

Enter information about monarch caterpillars in your yard, and help researchers get a sense of the health of the monarch population that year, and how and when they’re migrating.

Great Sunflower Project

Record the number of pollinators visiting your flowers, and help researchers map pollinator activity across the country.