I’m driving to spots around Leon County in search of native species. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? I could begin any number of blog posts that way; I’m looking for this rare plant or that endemic bird or salamander. Not so today, however. My companion has a shovel, but the things we’re looking for are not buried in the soil- they are the soils.

Soil types have names, just like plant and animal species, and areas where they’re known to be found. Our area’s ecology is as much connected to Orangeburg, Kershaw, and Ortega as it is to wood storks, gopher tortoises, or live oaks.

“When you think of an ecosystem as a whole,” says Mark Tancig, “and this could be an ecosystem in the National Forest, or this could be the ecosystem that makes up your lawn and garden, it includes the animals, it includes the plants. But something that we don’t think about is the soil.”

Mark is the Horticulture Extension Agent at UF/ IFAS Leon County Extension. People come to him with questions about plants. Maybe their trees aren’t producing fruit, or become diseased. Is the insect on this pepper plant here to eat it, or to help it? Any number of factors affect how a shrub or a wildflower grows. But the health of a plant starts in the soil where it spreads its roots.

So we’re going to go dig some holes, and see what “species” of soil are underneath us in different parts of the county.

Soils North and South of the Cody Escarpment

Mark has chosen dig sites based on a geological feature that divides our area, an ancient coastline that has been appearing in more and more of my stories of late.

The Cody Escarpment might be the secret to the high biodiversity of north Florida ecosystems. It’s a change in elevation that, millions of years ago when sea level was higher, formed a coast. To the north, the high ground. In Tallahassee, that’s the Red Hills, and moving west, it’s the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines region.

South of the scarp, the low ground. The Woodville Karst Plain was once ocean bottom. Sandy soils form a thin layer over our limestone aquifer, and water moves freely between the surface and the subsurface through sinkholes, springs, and ephemeral wetlands.

The Bluffs and Ravines are considered a top biodiversity hotspot in the US, an epicenter of the overall species richness in north Florida. This richness is due in part to changes in elevation, a multitude of different types of waterways and wetlands, and a diversity of soil.

The centerpieces of the Bluffs and Ravines region are the geologically rare steephead ravines. These are carved into deep sandhills along the Cody Scarp, sandhills that were once beach dunes. Here, the sandy soil and its structure is responsible for a high diversity of plant and animal life, both in the ravines and in the longleaf savannas above them.

The soil and its structure similarly affects the flora and fauna of our home spaces.

Grain Size- Sand, Silt, or Clay?

We start to the south of the scarp, in the sandy soils around Lake Munson. Mark is going to dig a hole large enough for us to see a soil profile. There’s a lot we can see in a profile, and a lot we can’t. One thing we won’t see is the considerable microbe activity. Mark tells me that a teaspoon of soil has more microbes in it than there are people on Earth.

What we can see is color, and texture. If the hole is deep enough, you can see bands in different shades of grey, brown, yellow, or red.

“When we think about soil- again, it’s a living thing- it’s made up of either sand, silt, or clay.” Mark says, “And that comes from the break down of rocks. So this sand that we have here was at some point a part of rocks. Maybe part of the Appalachian Mountains that has made its way all the way down to Florida.”

The difference between sand and clay is in the size of the grain.

“Sand grains- really, really big.” Mark says. “Silt- somewhere in the middle. And clay would be these tiny, tiny little grains. The more of these larger grains you have together, you have these big sand grains with lots of space in between because they can’t pack together tightly.”

South of the Scarp: Sandy, Well-Drained Soils

Here by Lake Munson, Mark has dug his hole. In the soil profile, we see dark streaks near the top. This is the topsoil, in which organic matter such as leaves break down and add nutrients and microbial activity to the soil.

Further down, we see lighter and darker shades of brown. This is a sandy soil, with those larger, odd shaped soil particles. There’s a lot of space between the grains, which means there’s free movement of air and water.

“Healthy soil is half space,” says Herman Holley, co-owner of Turkey Hill Farm in Tallahassee. “So when you have healthy soil and you have a big rain, it absorbs a tremendous amount of it before it’s saturated and water starts to run off.”

As we learned when we visited the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve last summer, water drains through sand pretty fast. The plants that grow in this environment have roots adapted to taking as much water as they can as it drains below them, and to thrive with less moisture.

But what about your garden? If you live south of the Cody Escarpment, you can select native plants adapted to sandy soils. This is ideal for wildlife gardening, to select plants appropriate to your setting, but what about your tomatoes and peppers and all? We’ll talk about building soil in a little bit, and much more in our next post.

But now, let’s head north of the scarp.

North of the Scarp: Surprisingly, Still Sandy Soils

The Leon County Extension Office is not far from Lake Munson, but it sits just north of the Cody Escarpment. For Tallahasseeans, a good landmark for the scarp is the North Florida Fairgrounds, and Tram Road. After a ten minute drive, we’re out of the ancient ocean and up on the high ground.

Mark picks a spot in their demonstration garden. After a few shovel-fulls, he digs past the mulch and topsoil. “Okay I see we’re getting down to some orange stuff down there.”

That orange stuff has a name: Orangeburg. It looks like red clay, but-

“Even that orange reddish-soil up [here] in the north of Leon County, it’s actually more sand.” Mark says. “It’s just a little bit of the clay with the iron oxides that give it that red color of clay. Orangeburg is the main soil type of these kind of Tallahassee Red Hills. But it’s Orangeburg fine sandy loam is the classification of that soil type.”

So there’s clay in there, but it’s not all clay. If it was all clay, those smaller soil grains would stick closer together, and there’d be much less air and water movement.

“You don’t want all sand; you don’t want all clay.” Mark says. “Ideally you’ve got something right there in the middle that makes water kind of cruise through slowly, but not so quickly that the plants can’t pick any up. And also you want air movement moving throughout those grains, because roots actually need oxygen.”

Building Soil | Adding Life to Rocks and Air

So far, we’ve learned that soil is rocks and air. Another component of soil, though it makes up a smaller percentage, is key to the health of your plants. We can see it in the darkness of the topsoil in our profiles.

“One thing homeowners can do is constantly be adding mulch, compost, to develop that really nice topsoil layer, organic matter.” Mark says.

In nature, leaves fall, plants and animals die. Something I love to see on a hike is a fallen log exploding with mushrooms. The mushrooms are breaking down the wood and turning it, along with the rest of the decomposing flora and fauna, into topsoil.

There are ecological benefits to letting leaves lie, even in just a few spots in your yard. In garden beds, mulch and compost can add the nutrients your plants need. The processes through which microbes make nitrogen available to roots also change the soil structure, so compost can rehabilitate poor or compacted soils over time.

That healthy topsoil layer will also help slow water down in sandy soils, and make clay heavy soils a little more spongey.

In our next segment, we’ll talk compost with Mark and Herman. And in the segment after that, we visit Smarter by Nature Farm in Quincy. They use ground cover plants and other regenerative methods to build soil and grow healthy plants.

What Kind of Soil do You Have in Your Yard?

You may be curious about the soil in your yard. Orangeburg is the soil gives the Red Hills region its name, but even though I live north of the scarp, my soil is a dark grey color. What is it?

Mark shared an online tool that shows you a soil map for any area within the US. The USDA Web Soil Survey uses data collected by the National Cooperative Soil Survey, which has mapped 95% of US counties by soil type.

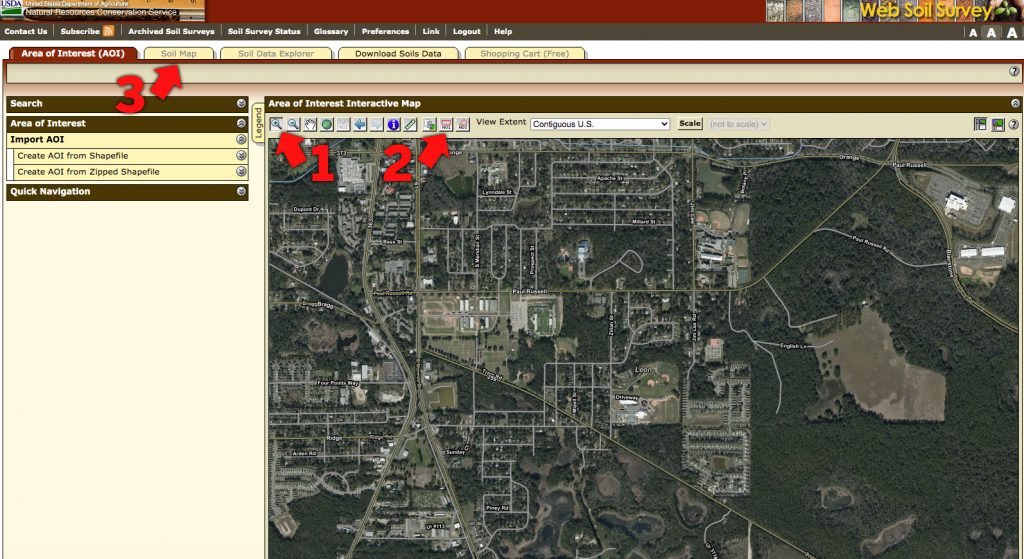

Here’s how it works. Go to their site and click the START WSS button.

Next, you’ll see a map of the United States. Use the Zoom tool (1) to drag a rectangle around your neck of the woods. Once you’re looking at the general area, you can use the Zoom in and out tools to set the area more precisely.

Next, drag an Area of Interest (AOI) shape over the area you want to inspect (2). Once that is defined, click the Soil Map tab (3), and you’ll see different zones, aligned with the area’s topography, showing the different soil types.

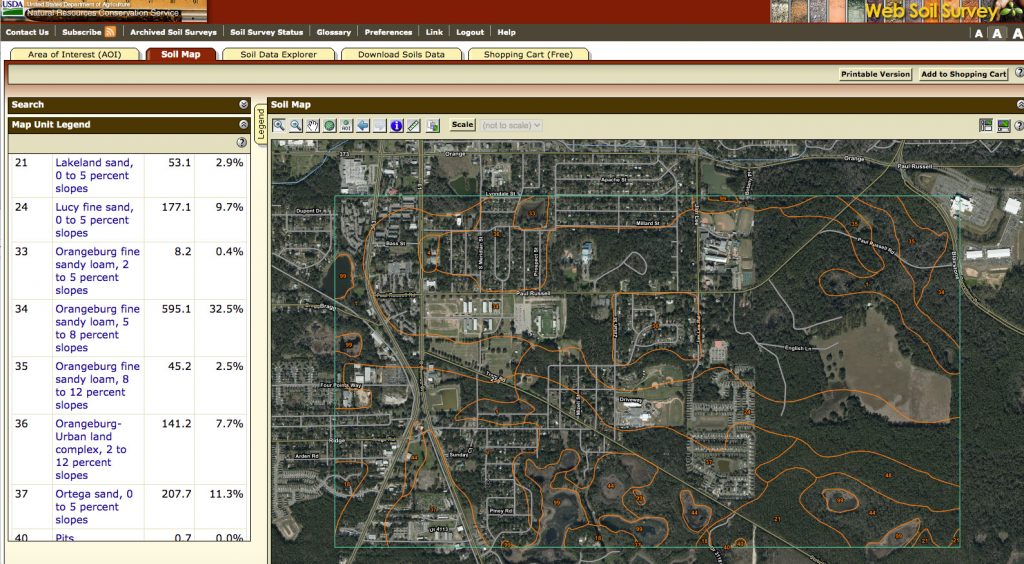

In this map, we’re looking at the section of the Cody Escarpment where the IFAS Extension Office sits, on Paul Russell Road. We see various numbers, which correspond to soil types listed in the Map Unit Legend on the left side of the screen.

Orangeburg Fine Sandy Loam

Along Paul Russell Road, we see areas labeled 33, 34, 35, and 36. These, as we see in the Legend, are Orangeburg soils. Just south of Tram Road, we see 37, Ortega sand, and 44, Pickney soils-occasionally flooded (these are wetland areas). The 99s are water.

I wanted to read more about Orangeburg, so I Googled Orangeburg Series, and found the USDA page for it. USDA has these basic looking info sheets on soils; no photos, but a lot of information. On each of these pages, you can read about the color of the soil, when wet, at different depths.

Orangeburg is dark grayish brown between 0-7 inches, strong brown between 7-12 inches, and then yellowish red (orange) below that, to 72 inches. You can see in the profile that Mark dug that it’s not uniform, but the USDA page is a good guide.

Mark gave a demonstration of how the clay particles stick together by squeezing the soil to make a ribbon. As he made the ribbon, you could see how the particles made his hand orange. Compare that to the way large sand grains kind of stick to you when you touch it.

You can scroll down the USDA Profile page to see information on geographic distribution and setting. “Orangeburg soils are on nearly level to strongly sloping uplands of the Coastal Plain.” It’s found in the states that make up the Coastal Plain, more or less the southeastern US.

Norfolk Loamy Sand

The USDA Soil Profile page for Orangeburg soil lists Norfolk and Thursa as the “only known series” in its family. So, just as animals with common ancestors are grouped into families and genera together, so are related soils.

Norfolk loamy sand is found in similar positions to Orangeburg, and is also heavily represented in the soil maps north of the scarp. It’s the soil I have in my yard.

Its top layer is grayish brown, turning to yellowish brown as you dig deeper. There are clay particles in the soil, but only as you get to a foot or more below the surface.

Ortega and Kershaw Sands

South of the scarp, we see different soil types than to the north. North of the scarp, the soils are loams, which are mixtures of sand, silt, and clay. Loam is considered an ideal soil type for gardens. They drain well, but still hold a good amount of moisture for plant roots to make use.

South of the scarp, the soil is sandier, holding less moisture.

We see sand from two locations in the video. One is where Mark dug a hole by Lake Munson, and another is a section of the Apalachicola National Forest called the Munson Sandhills. I used the mapping tool to see what kind of soil was in either spot, and both were in areas where Ortega and Kershaw sands bordered each other. Looking at the soil profile pages for each, I’ll venture a guess as to what each soil was.

Lake Munson- Ortega soil? Munson Sandhills- Kershaw?

Ortega fine sand is grayish brown to pale brown, much like the soil we saw in the hole Mark dug. Kershaw coarse sand is yellowish brown, darker in the topsoil, but lighter beneath.

So why do I think I was walking over Kershaw sand in the forest? I didn’t dig a hole there, but someone else had. In the gray and brown of the late winter forest, I’d see splashes of yellow in the distance, and walk up to find a gopher tortoise burrow. The area in front of a burrow is called the apron; it’s the soil dug out by the tortoise. So, while I didn’t dig down a couple of inches to see if the sand was grayish brown or yellowish brown, the tortoise had.

So, we have color as one indicator. Looking at the profile pages, I read more about their geographic setting and drainage.

Ortega soils are 48-80 inches above the water table for about half of the year. Just a few feet. Kershaw is an upland sand, at the tops of dunes, between 35 to 500 feet high. Gopher tortoises dig burrows that can reach 40 feet deep, and keep their burrows above the water table. If gopher tortoises are digging burrows in areas of adjacent Ortega and Kershaw soils, I’d wager they’d choose Kershaw.

Dig Deeper into Backyard Ecology

What can we do to invite butterflies, birds, and other wildlife into our yards? And what about the flora and fauna that makes its way into our yards; the weeds, insects, and other critters that create the home ecosystem? WFSU Ecology Blog takes a closer look.