Ten miles south of its head spring, the Wacissa River unravels like the frayed end of a rope. The main channel splits into braids, smaller streams branching away from and back into each other, forming river islands. Dr. Morgan Smith is driving us to one of these islands now. This is where, nine years ago as a PhD student at Texas A&M, he led an excavation of the Ryan-Harley site. I came one day to film his work, my introduction to underwater archeology in Florida.

When I produced that short segment, I never suspected that I was starting a documentary. One thing leads to another, and one good day in the field may lead to other related adventures, which sometimes circle back and return me where I began. Morgan has long since published his findings, and is now an Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga. Our return here is the first stop on a tour of prehistoric sites in the Aucilla/ Wacissa river basin. Later today, we’ll visit the famous Page-Ladson site, and then a site excavated by a current PhD student at Texas A&M (who’s also an FSU grad).

The Aucilla and Wacissa have a reputation in the world of submerged archeology.

“This is the epicenter of submerged prehistory on the planet,” Morgan says. “From, say, the Wakulla, east to the Suwannee, is the densest concentration of submerged prehistoric sites anywhere in the world.”

We’ll learn all about it and more in Finding the First Floridians (December 18 at 8pm ET on WFSU-TV). Now, though, I want to focus on Ryan-Harley. Let’s go back twelve or more thousand years, and visit a Wacissa River basin we’re not likely to recognize.

Discovering Ryan-Harley

First, we’ll make a quick stop in 1994. Brothers Ryan and Harley Means were scuba diving on a Wacissa River braid when they found a stone projectile point on the river bottom. They quickly found a second. Both points were made in the Suwannee style, which likely dates to the late Pleistocene: around 11,700 years or older. Any archeological material found in Florida waters is the property of the state, so they reported their finds to the Florida Bureau of Archeological Research.

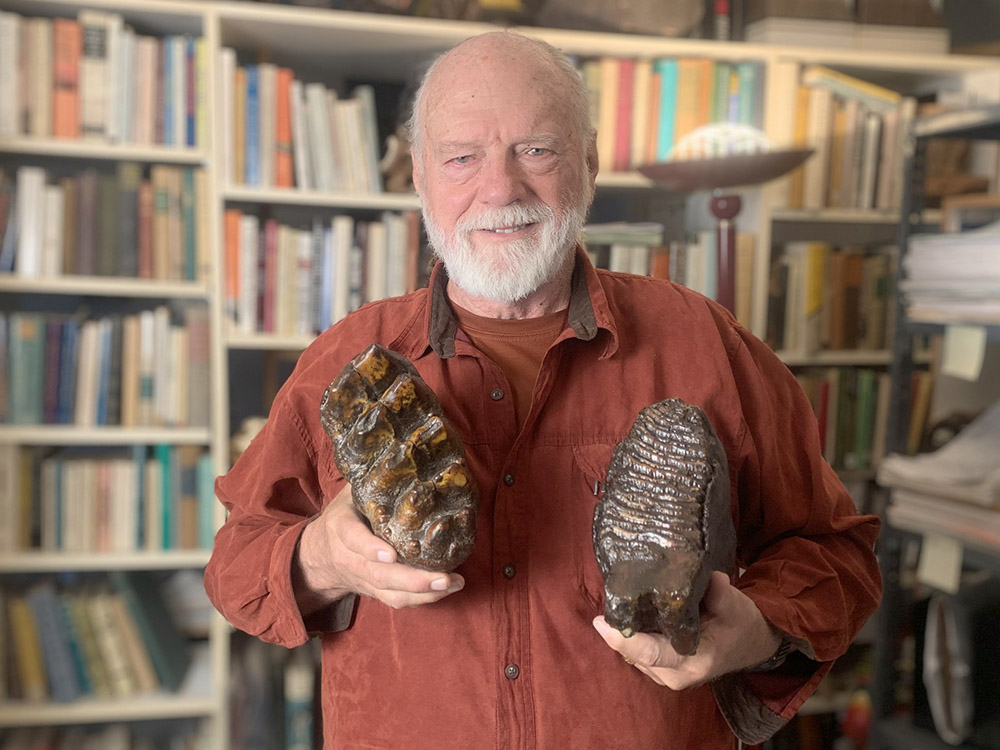

Ryan is the President of the Coastal Plains Institute and Harley is Florida’s State Geologist, though they were years from being those things. They are lifelong naturalists, raised by former Tall Timbers Director and founder of the Coastal Plains Institute, Dr. Bruce Means. As we learn in the upcoming documentary, Bruce learned to dive in the neighboring Aucilla River, where he’d encounter the bones of large, extinct mammals.

When Harley dove the site with state archaeologist James Dunbar in 1999, they found where the first points had eroded from the riverbank. Excavating the bank, they found more human-made material as well as the fossils of extinct megafauna. They were performing what James called “salvage archeology,” gathering the materials they could and securing the bank so that more materials didn’t leak out.

Why did they need to keep the bones and stones locked away under sediments?

Intact sediments are key to an archeological site; they are the best hope for knowing what pieces went into the ground together and, hopefully, when. In this case, it might finally have allowed archeologists to solve the mystery of the Suwannee people.

Dating the Suwannee culture

The Suwannee culture. It’s a name we’ve given a people based on where we first found the things they left behind. They made projectile points using a certain style, and when we find points that share this style, we know they come from the same larger group of people. That’s why projectile points are known as diagnostic artifacts: they identify a site as belonging to a specific cultural group.

The problem with Suwannee points is that archeologists have never been able to date them. To get accurate dates, artifacts must be in intact sediments with well-defined layers, alongside organic material that can be radiocarbon-dated.

Even without a firm date, researchers had come to a consensus that Suwannee points most likely dated to a period known as the Younger Dryas (~12,900–11,700 years before present). But Ryan-Harley artifacts were found with fossils of animals believed to have gone extinct by the start of the Younger Dryas. Either Suwannee was older than previously thought, or mastodons and other large mammals persisted here longer than they had elsewhere. Maybe there was a third possibility.

If the site dates to before the Younger Dryas, then Suwannee culture might well be one of North America’s oldest. The oldest well-dated culture in North America dates back to around 13,000 years ago: the makers of a projectile point style known as Clovis. Any site that dates older than Clovis would rewrite what we know about people in the Americas.

Harley and Morgan’s bet

When Morgan started excavating the site in 2015, he and Harley made a bet. Harley believed that Suwannee culture was pre-Clovis, whereas Morgan was more conservative. It’s a bet Morgan would gladly lose; a pre-Clovis site would be a major scientific find.

To answer that question, he’d need dates for artifacts and fossils. To truly understand the site, he’d need more than that.

“I really want to emphasize, it’s not one single line of evidence that we look for,” says Dr. Jessica Cook-Hale. She’s the Seismic Mapping Research Assistant at the University of Bradford, in the UK. “They always say, ‘extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,’ right? To paraphrase Carl Sagan.”

Let’s look at the multiple lines of evidence collected by researchers at Ryan-Harley over the years. Morgan and his team want to know everything they can about what brought early Floridians to this place, and about the world in which they were trying to make a living.

Reconstructing the Ice Age Wacissa River

The Wacissa is a place where we go to play. Kids jump from rope swings into the head spring to cool off on hot summer days. Hopping into a kayak or canoe, you can explore multiple spring runs along the river; Big Blue is a magnitude one spring and another swim hole. Any excursion on the Wacissa is rich with wildlife: wading and aquatic birds, numerous alligators and turtles swimming, kites and hawks overhead, and mullet jumping.

If you had to live off of the land, you could do worse than the Wacissa River. Could you imagine, though, if someone drained it of most of its cool, clean water? What if the densely packed trees of the floodplain forest surrounding the river weren’t there? What animals might we find then?

How do we start to understand how this area has changed over the millennia? Archeologists are always looking for fossils and artifacts in layers of sediment, but the sediment itself has a story to tell.

“We did about 800 different auger test pits all over this island,” Morgan says. The multitude of holes revealed the depth of different sediment layers at points all over the island. One layer is made of silts and clays deposited by water. “We were able to date the start of the modern Wacissa River regime,” Morgan says, “which starts around 8,000 years ago in this area.”

When people first arrived here, likely over 11,000 years ago, the Wacissa was not a regularly flowing river. During the ice age, much of the world’s fresh water was frozen in glaciers. Sea level was lower, as were water tables. When people left tools here thousands of years ago, this island was not an island.

Sand and dunes

The layer below the silts and clays is quartz sand, like that you’d find at the beach. Morgan dated this layer using a process called Optically Stimulated Luminescence, which, he says, “dates the last time sand and quartz screens are exposed to sunlight.”

This sand layer was deposited over 50,000 years ago. Using those 800 or so auger tests, Morgan recreated the layer’s topography, and it looked nothing like a river floodplain. The evidence showed that there was open sand here that was blown by winds. Scrubby trees and shrubs would have caught that sand and formed coppice dunes.

“What we found was that there’s a series of dunes that are oriented in the direction of late Pleistocene prevailing winds,” Morgan says. “They’re small in relief, but they are there. And it looks like the Suwannee people camped on the backside of one of these dunes. And nearby there’s a deep depression that might have been a water hole or a small, ephemeral pond that held water in an area a little bit longer than the surrounding landscape.”

It’s a far cry from the lushness we enjoy today. Suwannee people traversed this desert-like landscape to camp by a pool of standing water. There weren’t a lot of plants around them, but what of the animals?

Were mastodons at Ryan-Harley at the same time as humans?

“Original excavations found late Pleistocene fossils of mastodon, horse, extinct land tortoise, and muskrat in association with the Suwannee component,” Morgan says. This would indicate that people were here at the same time as animals that went extinct by the start of the Younger Dryas.

Those bones might solve the mystery of the Suwannee timeline. If the bones had enough collagen in them, Morgan could radiocarbon date them. In 1999, they had been too fossilized to test, but Morgan hoped that technology had advanced enough between then and 2015 to get a date.

“Unfortunately not,” Morgan says. No dates for the bones, and no dates for Suwannee. Morgan thinks he knows the reason.

“The issue was that we have this 50,000-year-old sand sheet underneath all of these peat deposits, which means that the surface that the Suwannee people lived on was exposed for a very, very long period,” Morgan says. “And my thoughts are that the fossils were relict on the surface when Suwannee people lived here.”

That sand surface was exposed for over 40,000 years. Perhaps a mastodon died, and over time, most of its skeleton decomposed or was gnawed on by rodents. What was left of it lay there for thousands, or tens of thousands of years before flowing waters washed another sediment layer over the top of it.

What did the Suwannee people eat at Ryan-Harley?

Morgan points out that extinct fossils comprise a small percentage of what they found at the site. Other sites we visit in Finding the First Floridians have full mastodon skeletons, or a much larger selection of bones. One has a tusk with what seems to be a scar made by a stone tool.

Ryan-Harley’s megafauna component was smaller, but the site did have a section dense with non-extinct bones, some with cut marks. Morgan says this is a midden, or trash pile.

“So we have a good idea of diet,” he says. “And what these people were eating was, basically anything they could get their hands on. They weren’t picky. There was waterfowl, there’s other bird, there’s fish, there’s rodent, there’s larger mammals like deer.”

Each excavation also found objects hinting at aspects of Suwannee culture that extend beyond basic survival.

James Dunbar’s team found ivory that had been crafted into a tool in 1999, and Morgan’s team found small beads. The beads are unusual for so early a site. They are decorative, an adornment.

As for the ivory, Morgan says, “It was probably an heirloom artifact passed down from people who were around when ivory was a workable, findable material on the landscape, which had to have been at least a couple of hundred years earlier.”

Perhaps the ivory shaft was passed down from generation to generation. It may have been an object of value to its holder. Or maybe it was just another tool, like the wood-cutting adze or the bone-scraper found at Ryan-Harley. Those tools have a story as well, down to the very stone from which they were made.

Settling the bet: is Suwannee culture pre-Clovis?

Morgan is trying to figure out if Suwannee is pre-Clovis. Clovis points are found across North America, from Alaska to northern Mexico, and coast to coast, and they have been consistently dated to around 13,000 years ago.

While Clovis is a widespread culture, other paleo-Indian point styles are regional. The paleo-Indian period refers to those first few thousand years of humans in the Americas. In the southeast, we have Suwannee and Simpson, which have not been dated. Folsom points, which have been found in the Rockies and Great Plains, have been dated after Clovis. Other regional styles are as muddy as Suwannee, but they’re all considered variants or descendants of the Clovis style.

Clovis is continental; these other styles are more localized. What does this mean? As Morgan explains, “It kind of looks like these Clovis ancestors are settling into certain geographic areas and kind of marking out territory that they’re adapted to and that they reside within.”

Once they settled into each region, they became new groups, local groups, and developed their own variations of the Clovis style. They adapted to the landscape and learned where to find the resources they needed. This includes chert, a type of sedimentary rock indigenous Americans used to make tools. Morgan’s colleague, Adam Burke, tests artifacts to find out where their material was sourced. His testing found that the tools at Ryan-Harley were made from local stone.

“The fact that they’re using mostly local material tells us that they’ve kind of more or less figured out the area and they know where the good toolstone is,” Morgan says, “which tells us that they’re a little bit more ingrained in the area and they know where to look for resources.”

Ryan-Harley, Page-Ladson, and beyond

Archeologists can tease a surprising amount of information from bones, rocks, and soil. From all of that, they try and tell a story. Here at Ryan-Harley, the story is that of a band of hunters camping behind a coppice dune. It’s a dry, sandy landscape, but they have a pond to drink from. They will take down a deer if they can find one, though they’ll settle for a muskrat. They wear jewelry and pass down heirlooms, and this area has been their home for a while.

It sounds reasonable and likely based on what science can tell us. Further excavations and analysis might alter some elements of the story, or fill in some gaps. The more sites excavated, the more information archeologists have to work with. Patterns emerge.

The Ryan-Harley site is a couple miles upstream from the Page-Ladson site, which sits in a sinkhole near the confluence of the Wacissa and Aucilla Rivers. One sediment layer at Page-Ladson contains mastodon poop and a knife that dates to over a thousand years before Clovis. We’ll tell the story of that knife in Finding the First Floridians.

Page-Ladson is one of the most significant American archeological sites because of that knife, but it also has other sediment layers. One of those layers has a Suwannee component, and Morgan says a date is forthcoming. He and Harley will finally settle their bet, and we’ll know a little more about early Florida cultures.

As Morgan said, north Florida is a hotspot for submerged prehistoric sites, and we can expect more excavations to come. We’re only just starting to learn about the first people who called Florida home.

Finding the First Floridians

In this post, we talked about the Younger Dryas, ice age sea level, Clovis culture, the Page-Ladson site, extinct megafauna, Pleistocene environments in Florida, and various other topics related to submerged prehistoric archeology. Each of those is its own story, and part of a larger story of Florida changing into the place we know today. It’s a story we tell in Finding the First Floridians.

People arrived here during a time of change that lasted thousands of years. When archeologists excavate a site, they create a new snapshot of Florida at a specific time, and of how people fit into its landscape. You can put the snapshots of various sites together like a flipbook. Flip the pages, and watch rising seas shrink Florida to its current size. See a landscape where humans hunted mammoths and mastodons turn into one where over twenty mammal species go extinct. Watch cultures react and adapt to changes in food and other resources.

How we’ve come to know about their lives is equally interesting. Our state is defined by its waters, and those waters are what make Florida an archeological hotspot. Creating a stable work environment under water is a challenge, and researchers have to be inventive. Down and dirty adventure meets methodical science, opening up new worlds.

Finding the First Floridians was commissioned by the Archaeological Research Cooperative and funded by a grant from the Florida Department of Historical Resources.