When I left for work this morning, I was ready for a day in front of a computer. Within three hours of stepping through my office door, however, I was standing in a forest above the Apalachicola River, in the presence of one of the most magnificent animals I’d ever seen up close. An Eastern indigo snake is an animal worth reshuffling your schedule for.

Yesterday, I had called David Printiss, the North Florida Program Manager for The Nature Conservancy. I’d looked at the weather forecast, and had seen conditions like those he had earlier described. A front was coming through, bringing rain, and today was going to be cool but sunny. The indigos would crawl out of their gopher tortoise burrows to catch that sun; but since it would take a little while for them to warm up, we were more likely to catch them basking.

In other words, a good day to see the indigo snakes released on the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve.

David was in the field when I called yesterday, and didn’t get back to leave a message until after I’d left for the day. So when I saw that blinking red light on my phone, I was hopeful. I checked the message, and yes, they were indeed going to be searching for snakes today.

The Decline of Indigo Snakes in the Florida Panhandle

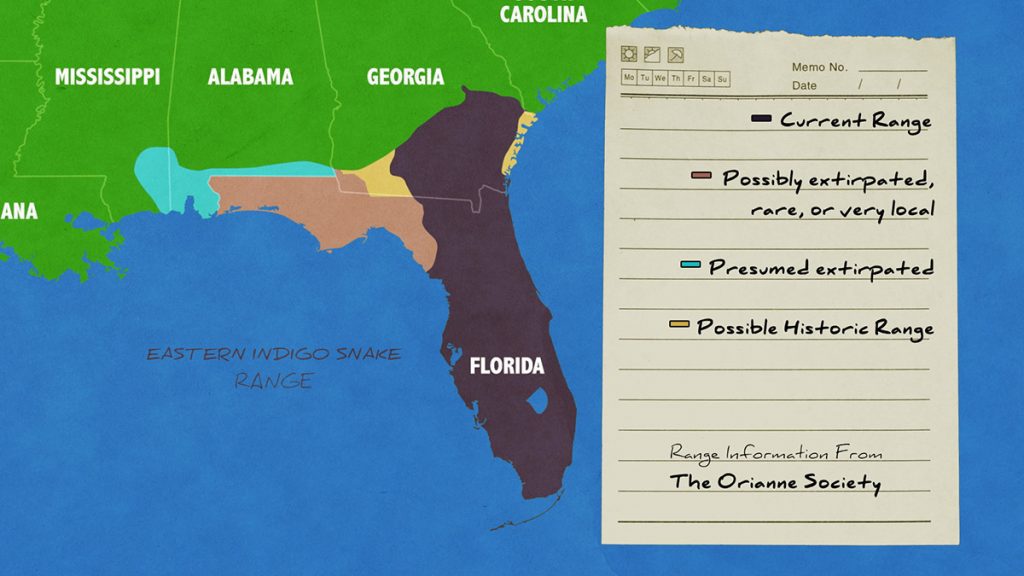

“The indigos once were common all across southern Alabama, southern Georgia, and the entire state of Florida, even down into the keys.” David says. Looking at the map above, we can see that they’ve all but disappeared from the northwest part of their range.

“The theory is, it’s because the gopher tortoises, which the indigos rely upon to escape the cold, to get into the burrows- the gopher tortoises have been eliminated from many of the conservation areas, or the populations are very depressed all across northern Florida.”

Gopher tortoises have declined across all of Florida, actually. But the relationship between these two animals is more critical up here, where cold blooded reptiles have to survive freezing temperatures. It’s not just indigo snakes that take advantage of these burrows; over three hundred different animal species shelter in them. Gopher tortoises are a keystone species, and you can learn more about them in an earlier video we produced.

In order for a tortoise to be able to make a burrow, it needs an open understory. Like so many plant and animal species we cover, it has declined because longleaf habitat had been clearcut for timber. Longleaf/ wiregrass ecosystems, burned every two to three years, are wide open places, accommodating diverse flora and fauna. But longleaf habitat only occupies 3% of its historic range.

In order to for indigos to thrive in north Florida, they need gopher tortoises. Gopher tortoises, in turn, need longleaf, wiregrass, and fire.

TNC’s Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve is not labeled on Google Maps, but it’s the area just south of Torreya State park. The green channels leading away from the river here are steephead ravines.

Reintroducing the Indigo Snake to the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines

The Nature Conservancy purchased the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve in the early 1980s. Over the last 40 years or so, they have rehabilitated the landscape, and burned regularly.

“And now there’s a quite robust population of gopher tortoises here at the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve.” David says. “And for that very reason, the Eastern Indigo Snake Reintroduction Committee selected ABRP as the first reintroduction site in Florida.”

Another project we recently covered also factored into the decision. Earlier this year, we visited a section of Torreya State Park where they’re restoring former pine plantation land to a sandhills, longleaf/ wiregrass, habitat. The Nature Conservancy is partnering with the park to restore the property, which is right next to ABRP. The additional 4,600 restored acres will give indigo snakes plenty of space to expand their population.

Indigo releases are made possible by partnerships between state and federal agencies, and nonprofits. The Central Florida Zoo’s Orianne Center for Indigo Conservation breeds indigo snakes to release here, and at a site in Alabama. The plan is to release 300 total snakes in ABRP over 10-15 years.

Every winter, on days where the conditions are right, David and his team go out and check on their snakes. Tagging along, I get an education in the ecology of indigo snakes, and the sandhill habitat.

Cavities of all Shapes and Sizes

Today’s searchers are David, his teenage daughter Genevieve, and TNC volunteer Annie Schmidt. Annie guided the RiverTrek 2012 team through a section of the Preserve above Alum Bluff (which we had to climb up from the river to get to).

We fan out in uplands surrounded by the Apalachicola River on one side, and a steephead ravine on another.

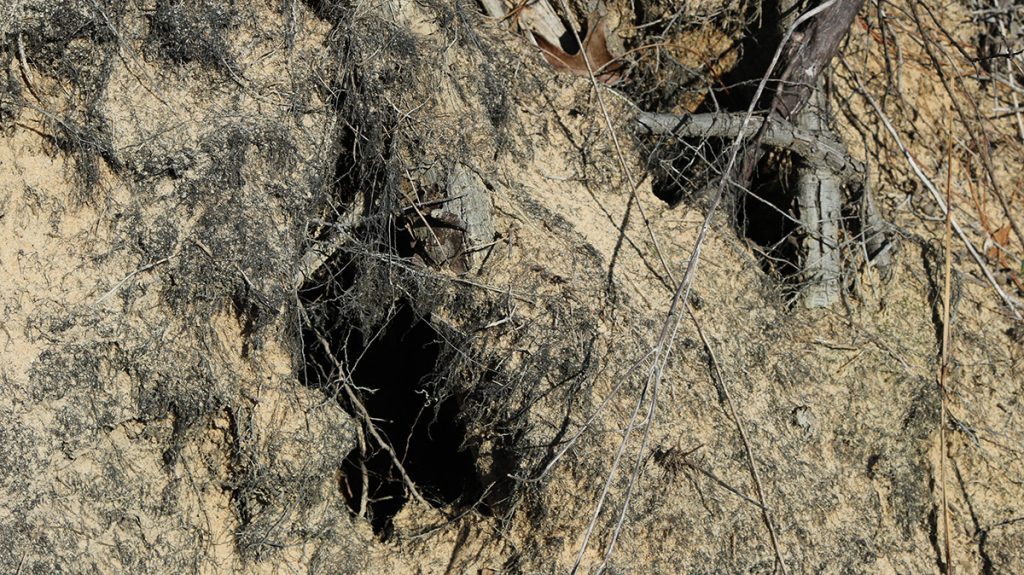

Early on in our explorations, David finds a possible indigo hiding space that’s not a gopher tortoise burrow. An overturned tree has created a mound around its roots, with small cavities where a snake might escape the cold. Hurricane Michael has provided many of these shelters. “Well, that is the mixed blessing,” David says. “With a lot of the trees that have come down, it provides a lot of habitat for the indigos to escape, and get down in the ground.”

We also find a large, animal made burrow that’s much too large to have been made by a gopher tortoise.

“I suspect that is a fox or coyote den.” I remember camping at Torreya State Park, not too far from here, and hearing coyotes howling at night. I can picture them sleeping in there now, after a night of prowling.

Other wildlife in the Sandhills

The coyote/ fox den isn’t the only sign of life we see while walking around. David points out this young longleaf pine:

“This is from a male deer,” David says. “They rub their antlers on small trees. They seem to have a preference fr the pine trees. And you can se the sap leaking down here. We think it’s to help with the parasite load.”

Tree sap seems to help with pests that might bother deer. David points out that much of the trees vascular tissue has been stripped, and this pine is now vulnerable in a fire. It’s a behavior that endangers trees, and unfortunately, deer also seem to like doing this to Torreya trees.

Bluebirds are flying just out of camera range. I stop to try and film one that immediately flies off. David notices an interesting animal on the tree next to me.

David says it’ll grow to about three times that size, and is the sort of animal an indigo snake might eat.

Messages in the Sand

As we’re walking around, David and I talk about various things we see, and the questions that bubble up in my mind as I take in the plant and animal signs he points out. And I just have to ask a question my six year old had about Indigo snakes and gopher tortoises: How do they get along inside the burrow?

“Little is known about their day to day interaction. But we know they’re down there at the same time.” David says. Researchers have peeped down into burrows, and seen multiple animals in there at a time using specialized cameras (you can see this kind of camera in action in our gopher tortoise video). “You go down, and you see a snake. And you down a little further, and you might see a gopher frog. You might see a mouse; you see a bunch of cave crickets. And then you see a gopher tortoise behind, because they generally tend to be facing downward when you do that. But they all seem to get a long quite well.”

Everything from burrowing owls to eastern diamondback rattlesnakes (a favorite meal of indigo snakes) use the burrows. And so you want to see a healthy number of active gopher tortoise burrows in a longleaf forest. David gets excited to find a couple of juvenile tortoise burrows; it’s a sign that the population is continuing to grow.

As we inspect the burrows, we see signs of other animals entering and leaving them. When tortoises dig their burrows, they kick up a lot of sand. This is the apron of the burrow.

The aprons let us see the tracks of the animals that make use of the burrows. David is especially excited to see this subtle imprint:

Meet the Eastern Indigo Snake

“I would say, pretty sure that there’s an indigo in this burrow, or somewhere right around here.” He points at a slight groove in the sand. “You see this right here? That is a snake crawl. And because it- oh, I hear it! There he is!”

He leaps into the bushes behind the burrow, and comes up with:

The first two years they released snakes, 2017 and 2018, they implanted radio transmitters in their indigos. Because the transmitters’ batteries had the potential to start leaking after a time, those snakes have been found and their transmitters removed.

The Nature Conservancy knows they can locate the snakes in the winter, when they’re close to tortoise burrows. And each is implanted with a Passive Integrated Transponder, which is not unlike an Avid chip you’d place in your pet. With a quick scan, David knows the identity of the snake he’s captured.

Looking her over, and hearing about her history, we can learn a few things about indigo snakes.

A Little Bit About Indigo Snakes

The first thing David notices is the milkiness of her eyes.

“This animal looks as if it is going to shed soon.” He says. “The eyes are starting to get a little bit milky colored.”

Looking at the scales around her face, he mentions that researchers are looking into whether each snake’s facial patterns are unique, like a fingerprint.

We next talk a little bit about her habits, and the habits of indigo snakes in general.

“This is also the time of year that they breed, probably as a result of their coming up into the uplands and aggregating.” They have yet to find evidence of their released snakes breeding, though David earlier pointed out a burrow where they found two snakes. As more and more snakes enter this landscape, they’re more likely to find each other and decide to mate. As with any release program, wild breeding is a sign of success. If animals can increase their own numbers, without human help, they can sustain their population.

Next, Annie and Genevieve chime in. They both have stories about this snake. She may be docile when Genevieve holds her, but when it comes to other snakes, she’s downright murderous.

“They Eat other Snakes.”

Annie remembers finding her once, in the nearby ravine.

“We found her in the ravine, and she was in the ravine happily eating a banded water snake.” Annie says. Here’s a photograph they took:

Genevieve remembers checking drift fences on the Preserve on day. You can see drift fences in action in the stories we’ve done on striped newts releases. Drift fences block off portions of a habitat, and direct animals towards traps. It’s a good way to see how certain animals move across a landscape.

“One day I came, and there was blood all over our trap, which is very uncommon,” she says. This snake was inside. “At first I though she was injured. We think she ate another snake that was in the trap with her.”

One indigo put on a show during the first release here when it ate a copperhead.

Indigo Snakes | Apex Predator of the Sandhills Ecosystem

“The one really great thing about indigos,” David says, “for those that are scared of snakes, is they eat other snakes. In particular, the venomous ones. They really love diamondbacks and pygmy rattlesnakes, and copperheads.”

Snakes are predators. Indigo snakes are apex predators, and as such, affect the entirety of their food web.

“If you think about grey rat snakes, and red rat snakes [also known as corn snakes] that climb trees and eat birds, in particular our songbirds,” David says, “We think that is one of the reasons that songbirds are getting more and more rare, is that the eastern indigo snake is not there to keep those rat snake populations in check.”

This is how apex predators regulate an ecosystem. They control the numbers of the animals they eat. Those animals, in turn, control the numbers of the animals they eat. Those lower level animals may eat plants or insects. When you remove any animal a habitat, it has effects that cascade through the food web. An excess of certain animals means that certain other animals or plants might see a decline. Th animals at the top help maintain balance.

Safe Return Home

When we’re done getting video and telling stories about this eastern indigo, David places her on the ground in front of the burrow where we found her. She wastes no time in slithering in.

We don’t see another snake today. But twenty to thirty indigo snakes will join this one every year for another decade or so. Across the street, on the Sweetwater Creek Tract, waste high longleaf pine will continue to stretch upwards. In a nearby restoration plot, wiregrass will sprout from bare, cleared earth.

I’ll be interested to visit this place in ten years or so, and see how it’s all coming together. As we’ve said before on this blog, it’s a project that’ll take over a hundred years to truly complete, to restore a longleaf habitat. But while they may be making something that future generations will most enjoy, it can be satisfying to see the habitat grow richer over time.