Dr. David Kimbro FSU Coastal & Marine Lab

Since I started working at FSU’s marine lab, I have frequently cast longing looks at a local study system that hasn’t been examined in over 50 years. Back in the 1960s, the world’s most famous ecologist (Bob Paine) was a post-doctoral researcher working at FSU’s Marine Lab. It was at this time and place where he began developing some of the concepts that would transform the field of ecology.

Since I started working at FSU’s marine lab, I have frequently cast longing looks at a local study system that hasn’t been examined in over 50 years. Back in the 1960s, the world’s most famous ecologist (Bob Paine) was a post-doctoral researcher working at FSU’s Marine Lab. It was at this time and place where he began developing some of the concepts that would transform the field of ecology.

Every month for 2 years, Dr. Paine wandered out to a sand bar in Alligator Harbor at low tide to count the different gastropods (snails) there. But this wasn’t your ordinary assemblage of snails. In fact, these snails represent the world’s largest and most diverse assemblage of predatory gastropods. The top-dog (horse conch) snail can reach the size of a football. And when it decides to visit the bar in the summer months, many of the other smaller snails, which were the top dogs in the winter, disappear. This then appears to open the door for a bunch of other even smaller snails to set up shop on the bar.

Picking up where Dr. Paine left off, we are asking some of the same questions on this bar that we are asking about oyster reefs: Does the horse conch structure this system mainly by scaring other gastropods or by eating them? When the horse conch isn’t around in the winter months, who does all the scaring and eating of the smaller snails? Do these interactions play out differently across this large sand bar (i.e., is it more dangerous by the water line compared to the center of bar that’s farther from the water)? And finally, how do these dynamics affect bivalves within the sediment (prey of smaller snails) and the water filtration services that they provide?

While you might think that we are one-trick ponies by transplanting the same oyster questions into this gastropod system, well… you are right! But that’s what ecology is all about. We want to see if our predictions about the ecology of fear play out similarly in a different system. If yes, then great! But if not, well…that’s cool too because we can figure out why things differ. And while the oyster project occurs across latitude, we still have the spatial thing going on in this sandbar; however, we are dealing with 0.1 km instead of 1,000 km!

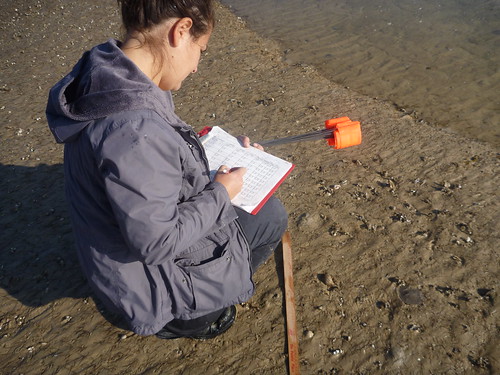

Luckily, in October of 2010, we welcomed a new visiting research student, Cristina Lima Martinez. Cristina comes to Florida from Vigo-Galicia, Spain and recently graduated from the University of Santiago de Compostela (USC) with a degree in Biology. After graduation, Cristina applied for an internship with the Spanish Ministry of Education in order to gain more research experience in marine systems. Out of 22,000 applicants, Cristina was awarded the research internship and we are extremely honored that she chose to conduct her internship at our laboratory because we needed someone to take on this project full time.

Over the next ten months, Cristina will lead this project and she’ll periodically write some blog posts to let us know what’s going on with all of those gigantic and diverse snails.

Best,

David

1 comment

[…] often talk about similar research questions or ideas in the context of different projects. As David mentioned in his description of the Baymouth Bar project, this overlap is usually intentional: as ecologists, we’re interested […]

Comments are closed.