Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

I was happy to hear that our station was going to create a game where children would learn about the movement of water in our area. Not enough people know where their drinking water comes from and where it goes. The short answer is: from the earth, and back into the earth. The longer answer led me to the specific place that drains FSU, FAMU, TCC, and Tallahassee’s downtown. The water we drink and the water we use for recreation in lakes, rivers, and on the Gulf, that water is all part of a system. There are subsystems within that system. There is the manmade network of pipes and treatment facilities that take water from the aquifer and place it in our homes; or the aquifer itself, replenishing with rain and feeding springs.

With Water Moves, WFSU aimed to teach children about systems thinking. Our local game is part of a larger initiative from PBS Kids Digital, which wanted something that had kids running around to compliment an upcoming computer game. Six teams of six kids had the same goal, to fill their buckets (houses) from a central pool (the aquifer) using tools they bought by earning points. Jamie Shakar from the City of Tallahassee then talked with them about the actual system, through which rain sublimes into the ground and is filtered through sand, clay, and ultimately limestone, finally reaching the sites where the city pumps our water.

In our Red Hills EcoAdventure, I made a connection between sinkholes in our lakes and our drinking water . Technically speaking, the water we drink does not come from surface water (lakes and rivers), but from groundwater (filtered and made clean as it makes its way down). To our second presenter of the day, though, all water in the aquifer is connected and must be protected.

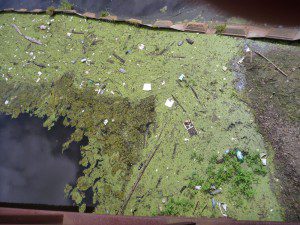

Karen Rubin is with the City of Tallahassee’s TAPP (Think About Personal Pollution). She showed that, as rain falls and filters through the ground into the aquifer, it also travels off of lawns and parking lots and down streets, looking for a low point. As this is how water flows, the low points tend to be lakes. For the most urban areas within Tallahassee, that low spot is Lake Munson. It is the most compromised body of water in our county. It is fed by Munson Slough, which runs through Lake Henrietta along the way. I visited Lake Henrietta, where the county has built barriers to catch some of our trash and keep it out of Lake Munson. What I saw, and smelled, kind of surprised me. I thought that the Munson Watershed’s problems would be more subtle, evidencing themselves in water quality readings on a table in a report. I was wrong.

What is being carried into Lake Munson? Think of our roadways, and all of the car exhaust that hits it. Do you notice a little puddle under your car when you run the air? And in and around our homes. People fertilize their lawns and vegetable gardens (As we’ve covered before, an excess of nitrogen from fertilizers ends up feeding algae, which blooms, sucks up oxygen and kills aquatic life). We use pesticides to kill those ant piles that pop up everywhere. We pressure wash our houses with chemicals. Water washes off of our lawns, picking up these chemicals and compounds as it drains to that low spot in our watershed.

Now, if Lake Munson was the final resting place of these pollutants, we might well say “Munson can take one for the team” and let it collect our refuse. We have so many great lakes and rivers already. But Munson Slough continues southward from the lake. It disappears down Ames Sink and a percentage of its water end up in Wakulla Springs.

An anhinga, surrounded by hydrilla, on Wakulla Springs. By occupying the space where water runs against vegetation, hydrilla may have prevented apple snails from laying their eggs and ultimately depriving limpkins of food.

Wakulla Springs has an outline of a limpkin on its sign. And while some comments in a 2012 post regarding limpkins offer some hope for their return, that bird disappeared from the park in the 1990s. No definitive cause has been determined, but many look at invasive hydrilla as a culprit. Fed by excess nutrients, it is a major presence in Wakulla Springs. So much so that it encroached upon the bases of plants where apple snails lay eggs. When its source of food disappeared, there was no reason for the bird to stay.

Johnny Richardson is a water quality scientist with Leon County. He told me that while 11% of the nutrients in Wakulla Springs are known to come from streams and sinks, they don’t know exactly how much comes from the Munson system.

And while the water that flows from Wakulla Springs into the Wakulla River is considered compromised by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, the system seems to clean it before it reaches the lower Wakulla, where it meets with the St. Marks River. St. Marks is a town that celebrates its fishing heritage with a Stone Crab Festival that we visited last year. While we in Tallahassee are connected through water to this fertile fishing ground, and to the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, our pollutants seem to dilute or get filtered out before reaching them.

A television lies in algae just downstream of a dam on Lake Munson. From here, the lake flows into Munson Slough, through the Apalachicola National Forest, and into Wakulla Springs.

It’s hard to say how much one leaky car or one overzealous gardener might degrade our beloved natural resources. Tallahassee can take the blame for Lake Munson, accept that it has some negative influence on Wakulla Springs, and feel okay that it isn’t contaminating seafood in St. Marks. What we do know is that we can make the problems better or worse. We can control this.

Over the summer, we’ll look at ways to reduce our personal pollution. For instance, instead of leaving a TV and its toxic innards on the curb for a few days, or heaving it into a lake, you can take it to Leon County’s Solid Waste Facility. It’s a little out of the way, but maybe you were going to Tom Brown Park or Walmart anyway?

Also over the summer, we’ll get back to the fun EcoAdventures. Also, Randall Hughes and David Kimbro will look back at the research into salt marsh, oyster reef, and seagrass bed ecology that we’ve been following over the years. Our area has some amazing ecology, and there are places we haven’t been and connections we haven’t yet made. I never tire of learning how it all works.

Follow us on Twitter @wfsuIGOR