Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

RiverTrek paddlers are raising funds for the Apalachicola Riverkeeper, an organization whose mission is to “provide stewardship and advocacy for the protection of the Apalachicola River and Bay, its tributaries and watersheds…” (participating media members do not raise funds). At the end of the paddle, on October 12, there will be a reception in Battery Park in Apalachicola. There, people can greet the paddlers and bring non-perishable food items in benefit of Franklin’s Promise. Franklin’s Promise aids the families affected by the failure of the Apalachicola Bay oyster reefs.

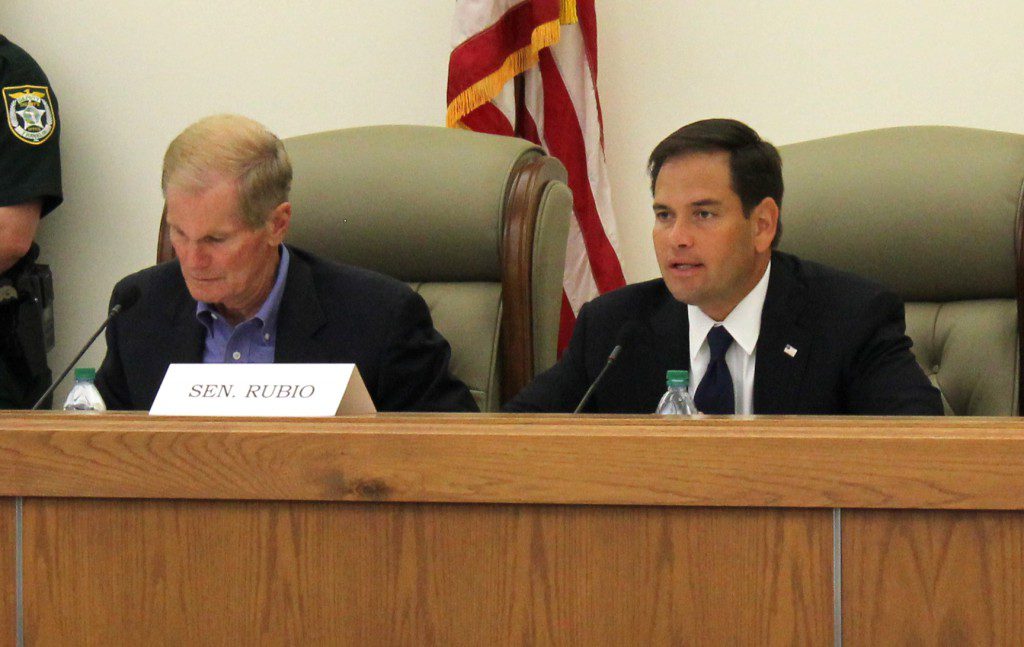

“The Good Lord giveth, and Georgia and the Corps taketh away.” Those words were spoken by Jon Steverson, Executive Director of the Northwest Florida Water Management District. He was testifying before Florida senators Bill Nelson (D) and Marco Rubio (R) during a special field hearing to address the collapse of the Apalachicola Bay oyster fishery. The high-profile event, held two weeks ago in Apalachicola, marked almost one year into a particularly turbulent era for this region. Just one year ago, I was preparing to kayak the Apalachicola River for RiverTrek 2012. The winter bars in the bay were just days away from opening. When they did, a lot changed, including the nature of the RiverTrek videos we were to make, and the In the Grass, On the Reef project as a whole.

“The Good Lord giveth, and Georgia and the Corps taketh away.” Those words were spoken by Jon Steverson, Executive Director of the Northwest Florida Water Management District. He was testifying before Florida senators Bill Nelson (D) and Marco Rubio (R) during a special field hearing to address the collapse of the Apalachicola Bay oyster fishery. The high-profile event, held two weeks ago in Apalachicola, marked almost one year into a particularly turbulent era for this region. Just one year ago, I was preparing to kayak the Apalachicola River for RiverTrek 2012. The winter bars in the bay were just days away from opening. When they did, a lot changed, including the nature of the RiverTrek videos we were to make, and the In the Grass, On the Reef project as a whole.

U.S. Senators Bill Nelson (D) and Marco Rubio (R) at the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation field hearing Apalachicola on August 13.

As I prepare to cover RiverTrek 2013 (October 8-12), the answers to the Apalachicola’s water flow problems remain elusive, and frustration remains high. Much of that frustration is aimed, as one might gather from the first sentence of this piece, at the state of Georgia and the Army Corps of Engineers. Thirteen days into the job as Mobile District Commander, Colonel Jon Chytka absorbed decades of displeasure at the Corps’ management of the ACF basin. “I’m going to try to find out why they sent you,” said Senator Nelson, “Why didn’t they send the generals that I’ve been talking to?” Part of the frustration stems from the rigidity with which the Corps follows the ACF Water Control Manual, and their interpretation of the authority granted them by congress. The economic impact of fresh water on Florida’s seafood industry is not given as much weight as its economic impact on Georgia agriculture. The Endangered Species Act of 1973 is the only guarantor that the river flow is not set below 5,000 cubic feet per second (cfs), which is how low it stayed for 10 months starting May 1, 2012. That qualifies as the lowest river flow in recorded history, and only endangered mussels and gulf sturgeon kept it from being lower. Senator Rubio asked whether the Apalachicola oyster would qualify for such protection. Crassostrea virginica, the common oyster, is the main oyster species found on the east coast of this country and in the Gulf of Mexico. The oysters you see on the fringe of the coast are the same species as the larger ones harvested from the floor of the bay. Apalachicola oysters are the same species as Chesapeake oysters. To the letter of the law, and despite massive decline in oyster reefs worldwide, it is not an endangered species.

This oyster was retrieved from Dr. David Kimbro’s oyster experiment in Apalachicola Bay. They found it dead, with its meat having been eaten. Like many of the dead oysters they’ve found, it has oyster drill egg sacs growing on it. Each of the sacs (here growing on the “chin” of the oyster) contains 10-20 drills. Low freshwater input to the bay increases its salinity, making the bay hospitable to oyster predators such as drills, crown conchs, and stone crabs.

A further source of frustration with the Corps is the speed with which the Manual is being updated. As Col. Chytka pointed out, the process began in 2008 and was complicated by lawsuits, the amount of input from stakeholders in the affected states (over 3,000 comments), and the “technical complexities” of the system. He projected that a draft of an Environmental Impact Statement would be ready in the Summer of 2015, after which they’d reopen it to comments and then finalize by 2016. The oyster industry may not have that kind of time. “I don’t see any hope for the near future,” said Shannon Hartsfield, President of the Franklin County Seafood Workers Association. “We don’t have a near future.”

The best-case scenario for the bay, as determined by the University of Florida’s Oyster Recovery Team, is full recovery within a couple of years. That’s dependent on being able to place a significant amount of oyster shell at the bottom of the bay. So far, Hartsfield estimates that they’ve covered 35-40% of Cat Point, historically one of Apalachicola’s most productive bars. By the end of the current shelling project, he believes that they’ll have covered 50% of another of the bay’s main bars, East Hole. So, in addition to fresh water, oysters will still be lacking adequate substrate where spat could settle. Additional funding will be needed to cover the bars fully. There is, though, a glimmer of hope.

While frustration has remained high, so too has passion for the ecosystem and compassion for the people affected. Says Hartsfield, “This is the first time, ever, out of all this disaster that Franklin County has experienced in the commercial (seafood) industry, that we’ve had any recognition. And we appreciate it greatly.” That recognition drew dozens to the steps of the Franklin County Courthouse that day to show support. It has drawn researchers willing to work with oystermen to find solutions. It has drawn a steady stream of regional and national media. And it drew the United States Senate to a fishing town on Florida’s Forgotten Coast. At the very least, lot of people are invested in finding a solution.

RiverTrek paddlers make their way to Sutton Lake, off of the Apalachicola River. Last year, the water was too low to paddle further into the lake, where the largest cypress trees in the Apalachicola watershed are found. With a year of healthy rainfall, this year’s paddlers will have better opportunities to explore the creeks and sloughs branching off of the river.

I’m one of the media members who have found themselves returning to cover the crisis, and it started with 105 miles of paddling. Last year at this time, RiverTrek was to be a different perspective on our local ecology than our marsh, oyster reef, and seagrass videos. A change of pace. Instead, it kicked off a year of content that connected the river with the coast, and with the people who care for and rely on these resources. I now find myself getting ready for this year’s journey with a better knowledge and feel for the story, but with much less certainty about the outcome. RiverTrek will end after five days. For this other, much larger Apalachicola adventure, we’ll all just have to keep on paddling.

For more information on RiverTrek 2013, visit the Apalachicola Riverkeeper web site. To watch videos from last year’s Trek, click here.

Music in the video by airtone. “Salt in the Blood” was written and performed by Brian Bowen.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number 1161194. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.