In 2024, three hurricanes hit Florida. Two of those were major storms, category-three hurricanes that landed within a couple weeks of each other. It has become an annual occurrence. Every late summer or early fall, at least one storm enters the Gulf of Mexico, and Floridians anxiously track its path and projected strength.

Over the last decade and half, we’re seeing more hurricanes, and more of them are category three or above. This is the result of warmer water in the Gulf of Mexico. Floridians are also experiencing harsher droughts, and sea level rise.

Climate instability is nothing new in Florida. It was, in fact, the norm for the first people to make their home here, and, over thousands of years, for their descendants as well. These people were entirely dependent on Florida’s land and water resources, but food sources disappeared, and the coast was unstable, always on the move. Climate warmed, and ecosystems changed. Some of those changes were sudden.

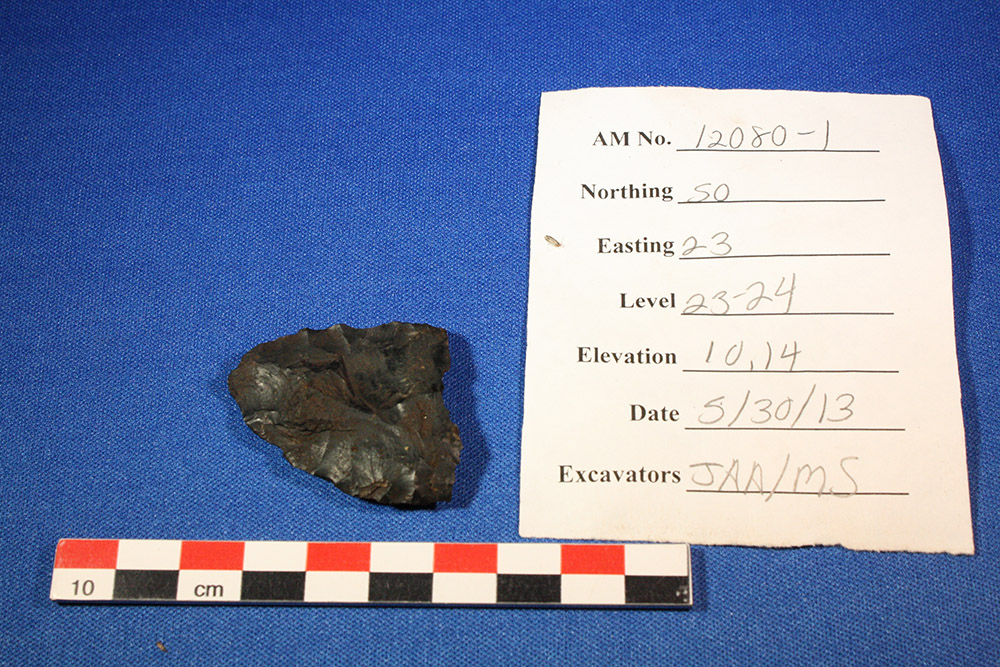

People living in the late Pleistocene had to adapt to survive. We know relatively little about them, but from what they’ve left behind, we can see their technology evolve and their behaviors change as the land changed around them. Archeologists may not always find a wealth of manmade materials at the oldest sites, but if they keep finding sites, they can see patterns, and they can compare those patterns with environmental reconstructions and the climate record.

By looking at as many clues as possible, researchers can start to answer the question, “Who were the First Floridians?”

Finding the First Floridians

WFSU’s newest documentary digs into the sediments beneath Florida’s abundant waterways. Here, archeologists are finding prehistoric sites, some of which are older than many had previously thought would be possible in Florida. Florida is an epicenter of submerged prehistory, and the last decade or so has seen a renewed effort to excavate sites.

- Chapter 1: Florida’s Ice Age Landscape

- Chapter 2: Rising Seas and Flowing Rivers

- Chapter 3: Prehistoric Cultures Adapt to Change

Cultures of the Paleo-Indian Period

Let’s start with what we know of the oldest known Floridians from what they left behind.

Page-Ladson

Florida’s oldest confirmed site is Page-Ladson, which dates to around 14,550 years ago. The star features of the site are a small knife and a mastodon tusk with what appears to be a cut mark. That’s a single piece of technology and evidence that humans hunted large game.

“It’s a couple of flakes,” says Nick Bentley, a PhD student at Texas A&M’s Center for the Study of the First Americans. “It’s a single biface. It’s difficult to interpret human activity based on that.”

Part of the difficulty lies in it being an isolated site. Another site of this age would give archeologists more materials to compare and contrast to it.

Clovis Culture

For decades, Clovis was believed to have been the oldest American culture, and it is still the culture against which all other ice age sites are measured. When any non-Clovis tool is found in a Pleistocene site, the question is whether it is pre- or post-Clovis.

What unifies this as a culture is that its projectile points are all created using a similar style (see the graphic further down). This makes it a diagnostic artifact, so that even if a site with a Clovis point can’t be radiocarbon-dated, it likely dates to a similar time as all the rest: between 13,050 and 12,750 years ago.

It’s an old culture that seemingly lasted for two to three hundred years, and it covered nearly all of North America. It suggests a people who covered a lot of ground. One reason for that might be that many of the animals they likely hunted, like bison and mammoths, migrated over large ranges.

Simpson/ Suwannee Cultures

These, too, are diagnostic point types that would have been made by people with a shared culture. Unlike Clovis, neither of these types has been dated, leading to some debate over whether they were pre- or post-Clovis.

One big difference between these cultures and Clovis is that they’re more localized to Florida and the surrounding states (refer to the blue dots in the map above). Dr. Morgan Smith explains that this likely means that these cultures descended from Clovis.

“It kind of looks like these Clovis ancestors are settling into certain geographic areas and kind of marking out territory that they’re adapted to, and that they reside within,” Morgan says.

Morgan excavated the Ryan-Harley site on the Wacissa River, a site with several diagnostic Suwannee artifacts.

“Suwannee people had a flexible adaptive toolkit strategy, which we kind of expect from their ancestors that were very mobile,” Morgan says. “So they had things like adzes, woodworking implements, tools that were probably also used to work bone, wood-working instruments like scrapers, which tells us that Suwannee people are still overall uncertain about what they’re going to face because if you have a flexible tool kit, it’s probably because you’re not really sure what the next month or three months or year look like for you.”

Simpson and Suwannee cultures were not as mobile as their Clovis predecessors, but were still mobile. A flexible toolkit means they used fewer tools, and could travel more lightly.

The Younger Dryas: a Major Climate Event

Why did Clovis transition to smaller regional groups throughout the country?

When people first arrived here, it was already a period of climate change. Around 20,000 years ago was the end of the last Glacial Maximum, and the beginning of the end of the last ice age. As we covered in Chapters 1 and 2, much of the world’s water was frozen in glaciers, and sea level was 300 feet lower. Glaciers then started to melt, and sea level rose. This continued for thousands of years.

“The climate is overall warming and warming and warming,” Morgan says. “And then, within the period of a couple of generations, things go back to really cold, really windy, really arid.”

Morgan is talking about a climate event known as the Younger Dryas, which started around 12,900-12,700 years ago, and lasted about 1,000 years.

“If you look at the onset of the Younger Dryas, that probably happened over a few generations,” says Dr. Shane Miller, Associate Professor Department of Anthropology at Mississippi State University. “If you got people who are reacting to what the environment gives them for their foodway, or any kind of change in that, any perturbations to that in some way, they’re going to have to adjust. And that’s going to be reflected in the archeological record.”

“Animals die, plants die, ecosystems shift, sea level rises very quickly during punctuated points,” Morgan says. “And the Suwannee people live during all of this.”

Animals did die, which we can see in the sediments at Page-Ladson.

A Story Told by Poop Mushrooms

We met Dr. Angelina Perotti in Chapter 1. Angelina studies pollen in the sediment record to determine what kinds of ecosystems were at a given location over time. Think of this next time you dig into the soil in your garden. Look closely: can you see pollen grains? How about fungal spores? Soil has many stories to tell.

“What we’ve discovered recently is that there are fungal spores that can tell us a whole bunch of information about the environment,” Angelina says. “One of the most interesting ones in my opinion are coprophilous fungal spores. These fungal spores are primarily associated with large herbivore dung. So things like mastodons and mammoths are going to be contributing many more fungal spores to a record than something like a deer or rabbit.”

Coprophilus fungi are mushrooms that grow specifically in herbivore dung. Some of the species we find locally are bird’s nest mushrooms and Psilocybin cubensis. That’s right, magic mushrooms likely grew on mastodon poop.

Angelina measured coprophilous fungal spores at the Page-Ladson site. The 14,550 year-old layer contained the fossils of a few extinct mammal species. Moving upward in the sediments from this layer, she could see changes in pollen and fungal spores.

“And right at 12,700-ish, Morgan says, “the concentration of the spores in the sediment record at Page-Ladson just drops off the charts. So it’s just gone. That gives us a good idea of the date for megafauna extinction and extirpation in the area.”

This date lines up with the beginning of the Younger Drylas, and the end of Clovis culture.

Humans and Ice Age Megafauna

Mastodons and mammoths would have been a source of food, a single kill providing a large amount of meat. But Dr. Richard Hulbert, retired head of the Division of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Florida Museum of Natural History, is dubious that these largest of animals were a major part of the human diet.

“There are abundant numbers of small animals, too,” he says. “I don’t think we should discount that. Do you go out and hunt a mammoth, or do you try to take a deer or a couple of rabbits? In particular, in the warm months, most of the meat on them, if you kill a mammoth, is going to go to waste.”

Killing an elephant is a lot of work compared to other animals. In addition to deer, Richard shares that there are llama and horse fossils with human-made cutmarks.

Richard also points out that a mammoth or mastodon would have been more than capable of killing a human if attacked. As would one of the many predators that went extinct at the end of the Pleistocene. When humans arrived in Florida, it was home to four large cats. The smallest were Florida panthers. American lions and saber-toothed cats are now extinct. Ice age jaguars were here, and were larger than the members of their species currently living in South America.

Dire wolves were another large predator, and short-faced bears were a large, lethal animal. Even ground sloths were tall and had large claws, Richard points out.

The Loss of Keystone Species

Suwannee people had fewer food options than Clovis, but also fewer threats to their safety. The loss of almost thirty mammal species would have affected the rhythm of their daily lives, and disrupted the habitats they used.

“That’s when the cascade of ecological change happens,” Angelina says, “because megaherbivores are keystone species. And so when they are removed from a landscape, we see all sorts of ecological changes like vegetation change, but also increased fire.”

We talked about megafauna and fire in Chapter 1. Without animals to eat the fuel, the fuel burned more regularly. Florida is the lightning capital of the world, and our dominant upland habitats are adapted to regular fire; it drives biodiversity in longleaf pine ecosystems. But what would humans have made of a landscape that started burning more regularly?

Other changes in the land were climate-driven.

Angelina’s analysis of Page-Ladson showed that in the millennia leading up to the Younger Dryas, a hardwood forest had grown around the sinkhole, which indicated a wetter environment. Tree pollen starts to drop off as conditions dried during the Younger Dryas.

Unrelated research also indicates that there may have been an increase in strong hurricanes in Florida during the Younger Dryas.

Living through Sudden Change and Instability

Food sources and safety threats disappeared. Wildfires burned more regularly. Water sources became less reliable, and category five hurricanes might have become more regular.

We have no written record of the lives of Suwannee or Simpson people, and how they reacted to the sudden upheaval of their world.

“This was a rapidly changing climate,” Morgan says. “I’m sure that had an impact on longevity. It probably had an impact on animals’ well-being. So there was probably all sorts of problems associated with sourcing food and finding water, and that creates stress and malnutrition, which creates intergroup conflict. And I’m sure there’s all kinds of things that were missing.”

“What to me is even more interesting is what comes after the Younger Dryas,” says Shane Miller. “Because then you had the inverse happen. It ended as abruptly as it started. In a relatively short amount of time, it got warm. It started this warming trend that lasted several millennia.”

The Holocene Epoch/ Archaic Period

Another shift in climate, another change in projectile point technology.

“The archaic period, on the early end, is kind of one of the first big transitions in projectile point technology, where we move from these lanceolate shapes overall to the notched varieties,” Morgan says. “And the archaic tends to stem from 11,000 to 3,000 on the end… so there’s this huge chunk of time, whereas some of the other cultural periods are a couple thousand or a couple of hundred years.”

Suwanne and Simpson points are considered an evolution of Clovis points, whereas the Bolen points dating to the start of the Archaic are entirely different.

A note on names. Archeologists use the names of both geologic epochs and cultural periods. The Paleo-Indian period refers to cultures in the late Pleistocene epoch, which we call the ice age. When the Pleistocene ended at the conclusion of the Younger Dryas, the Holocene epoch began. The Holocene is the current geologic epoch. Culturally, the Archaic period also began around then, though there is debate about when exactly it started and ended. The archeologists I interviewed gave a range of dates as do online sources.

The important thing to remember is that a period of stability followed the upheaval of the Younger Dryas. The effect of this stability shows up in the archeological record.

A Period of Stability

“You’ve got glaciers that are melting, they’re adding a lot of water to the oceans and then it’s charging the aquifers in Florida,” says Dr. Melissa Price, Underwater Archeology Supervisor at the Florida Bureau of Archeological Research. “More fresh water, more resources, and then people start exploiting marine resources as well. So now you can have bigger groups.”

“We start to see people developing into complex centers where they have a base camp and they’re staging resources from around an area,” Morgan says. “This is where we see people adapting to the coast specifically for the first time. So they’re living on the coast.”

The increase in fresh water started rivers flowing, down to the coast to combine with salt water and create estuaries. The brackish mix would allow oysters to thrive and make reefs. We know that people started eating oysters in large quantities from the large piles of them they left behind, which we call middens.

“They have these gigantic shell deposits,” Morgan says, “some of which have burials in them, and some of them have funerary remains and artifacts from all aspects of daily life.”

Life, and death, look a lot different in Florida by the middle Holocene. People no longer have to move from sinkhole to sinkhole in search of water, or large game. They have all the resources they need within a relatively short distance, so they stay put and leave larger sites.

Mortuary Ponds

By the middle Holocene, burials became specialized and showed evidence of ritual. Melissa Price is interested in one of the most specialized burial practices of this period.

“I study middle archaic period mortuary ponds,” She says. “Florida has a unique cultural practice during the early and middle archaic period where people interred their deceased in saturated freshwater environments with a lot of peat. They were basically placing the deceased person in the sediment and they would use work stakes to hold the people in place, maybe to mark the burial.”

The best-known of these sites is Windover, near Cape Canaveral. The site was excavated by Florida State University in the 1980s, led by Dr. Glen Doran. Researchers found 168 individuals preserved under a shallow pond.

This type of burial was not widely practiced, and the sites all dated to between 5,000 and 7,000 years ago across central Florida. “It’s just very interesting to have mortuary ponds in a very specific region in Florida, very tight timeline.”

Florida Takes Shape, And Cultures Continue to Evolve

Between 6,000 and 5,000 years ago, sea level stopped rising. “That is when the barrier islands formed, coastal deltas formed,” Says FSU oceanographer Dr. Jeff Chanton. “And so that’s when people really could establish themselves on the coastline in a more permanent way. There’s evidence on St. Vincent Island that there was a large settlement there.”

That settlement is from the Woodland period, which followed the Archaic. This culture is known for its large oyster middens, burial mounds, and ceramics. If you’re interested in this period in our area, check out a pair of posts I wrote about the Byrd Hammock site on the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge.

On both St. Vincent Island and St. Marks, people ate oysters in places that were far inland when their ancestors first arrived in Florida. Indigenous Floridians changed with the land, surviving the toughest of times and thriving in times of plenty. This was their home in a deeper way than we can understand.

A Rennaissance of Submerged Prehistoric Archeology

The story of the First Floridians is remarkable, and it’s remarkable how we know what we know of them.

Many of the submerged sites in this film were found by recreational scuba divers. Diving into rivers and springs, people found projectile points, tusks, teeth, or bison horns. Archeology had always been conducted on land, but the wealth of materials under water was too much to ignore. in 1973 Charles Hoffman excavated what appeared to be a mammoth kill site in the Silver River. In the 1980s and 90s, Dr. James Dunbar and Dr. Michael Faught developed methods for excavating offshore and in rivers.

Dunbar and his collaborator, Dr. David Webb, excavated the Page-Ladson site and dated it to 14,500 years ago, a date that should have rewritten the history of people in the Americas. Submerged sites didn’t get the attention they deserved until a generation later, when a team from Texas A&M went back with Dunbar and re-excavated Page-Ladson, and confirmed his dating. They ended up in National Geographic.

Hoffman, Dunbar, and Faught inspired a generation of scuba-diving archeologists to work in challenging conditions, yet slowly and methodically. Page-Ladson has invigorated interest in this specialized segment of archeology, and shined a light on Florida waters. They’re looking for that next pre-Clovis site, to add to the story of the First Floridians.

Finding the First Floridians was commissioned by the Archaeological Research Cooperative, and funded by a grant from the Florida Division of Historical Resources.