On the way to Porter Hole Sink, I pass crowds of people holding either cell phones or fishing poles. The occasional drone flies overhead. Local historian Jonathan Lammers remarks that this will be the most documented of Lake Jackson’s dry downs. But, for all of the images and videos flooding social media, how much does the average person understand about Lake Jackson drying (mostly) out every few years?

People worry about fish, as they have for decades. Lammers scoured newspaper records of dry downs in our area’s four major sinkhole lakes: Iamonia, Miccosukee, Lafayette, and Jackson. A 1932 Tallahassee Democrat article referred to the drying of three of the lakes as an “emergency.” In 1939, Leon County started work to dam a sinkhole on Lake Iamonia as water drained into it, and a Democrat headline reported that fish were being moved. Lake Lafayette followed in 1950, and Lake Miccosukee in 1954.

Lake Jackson is the only large sinkhole lake to escape damming.

So where do the fish go? A few locals on the scene seem to know- those with the fishing poles. A lot of the lake bed is exposed, but there are still quite a few pools of water. There, people and wading birds alike have gathered to take advantage of fish not having so much space to get away.

What follows is a quick guide to the Lake Jackson dry down. We’ll look at Jonathan Lammers’ chronology of dry downs and area rainfall. What’s the correlation between the two? We’ll also share what biologists and geologists have shared with us about Lake Jackson and our area’s lakes in general.

For a deep dive into the geology of the Red Hills’ sinkhole lakes, and the forces that created them, check out our 2018 post on the Lake Miccosukee sinkholes. Also in 2018, we visited Fred George Basin Greenway, where Harley Means identified two sinkholes in the process of becoming lakes, and which dye traces connected to City of Tallahassee drinking water wells (sinkholes in our area drain into the Floridan Aquifer, the source of our drinking water and springs).

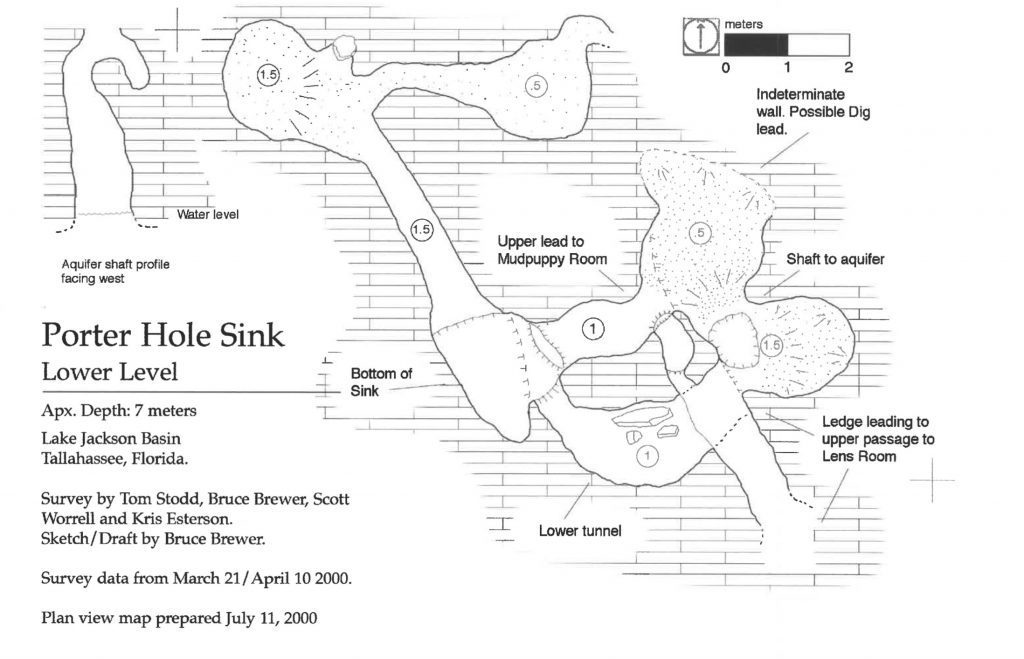

In 2018, McGlynn Laboratories conducted a dye trace study in Porter Hole Sink. The dye emerged from Wakulla Spring 35 days after divers injected the dye into the sink.

View Jonathan Lammers’ full Leon Lakes Draining Chronology here.

Lake Jackson Dry Down At a Glance

Retired Florida Fish and Wildlife biologist Michael Hill answered some questions for me regarding the dry down. Hill has been featured in previous segments on our sinkhole lakes, and even though he’s retired, he wants to dispel myths about what happens during dry down events.

Where do the fish go?

Hill wants people to know that fish do not dig down into the mud until the water returns, or swim down the sinkhole and into the aquifer. He points out that the lake basin is not flat, and that water remains in pools throughout. Some of the pools are fairly deep, actually. Many of the lake’s fish make it into these pools.

The dry down benefits fish in the long run. If the lake stays full, organic matter builds up and the lake bed gets mucky. Walking around the Porter Sink basin, we can see clusters of bowl shaped depressions. Hill says these are bluegill, or bream, nests. A mucky bottom is unsuitable for these nesting fish.

Eventually, that muck layer would float to the top, and plants would start growing in it. This forms floating islands of vegetation called tussocks. Hill showed us tussocks on Lower Lake Lafayette in 2014, and further explained the process in our 2018 post on the Lake Miccosukee sinkholes. Lake Lafayette has permanent earthen dams that have created three smaller lakes. Upper Lake Lafayette has the sinkhole, so Piney Z. Lake and Lower Lake Lafayette don’t drain.

As for the dead fish we see on the ground around Lake Jackson? Hill points out that raccoons, birds, and other wildlife eat these. They’re still a part of the lake’s food web.

Porter Sink Blockage

In that 2018 Lake Miccosukee post, we included photos of Harley and Ryan Means climbing down into Lake Jackson’s Porter Sink, and a map of the cave. Visiting today, streams heading from two directions seem to converge and flow under a large boulder. Michael Hill estimates that the opening is now about as big as a soccer ball.

That’s because someone illegally tried to stop the sinkhole by pouring cement into it.

And yet- the lake still drained!

Aside from the partially blocked Porter Sink, Hill says there are various smaller openings around the sinkhole that are taking in water. And it’s important to note that the sink itself isn’t responsible for the lake becoming empty. Hill describes four ways the lake level gets lower before the sinkhole becomes active:

Four ways the lake level gets lower before the sinkhole becomes active

- Evaporation: This is part of the water cycle. Water evaporates and floats up into the sky, forming clouds and eventually raining back down.

- Transpiration: Plants in and around the lake drink the water, and then “sweat” it out into the atmosphere.

- It Percolates Through the Lake Bottom: As we learned in segments on sandhill ecosystems and the soil types of our area, water passes down through sandy soils. Hill says a certain amount of water simply passes through the sandy soils beneath the lake, slowly into the aquifer.

- Other, Smaller Sinkholes: Hill says there are hundreds of smaller sinks throughout the lake basin.

During wet years, water leaves the lake, but also rains down into it. But what happens when the amount of rain is less than the amount of water that left?

When does a sinkhole lake dry down?

Loosely speaking, the Red Hills sinkhole lakes go dry after long periods of low rainfall. We experience cycles of wet and dry periods lasting a few years. Some dry cycles are dryer and more prolonged than others. A lack of rain over time does two things; it makes water lower in both the lake basin, and in the aquifer beneath it. Assistant State Geologist Harley Means explains what happens next.

“When the water levels in the underlying aquifer drop,” says Means, “And you’re not getting enough rainfall to fill the basin up, then you’ll get more water focused through the sinkhole. And then at some point, something triggers and the sinkhole opens up.”

Once the sinkhole opens up, the remaining water drains into it. It then stays dry until we get enough rain to fill the aquifer beneath the it.

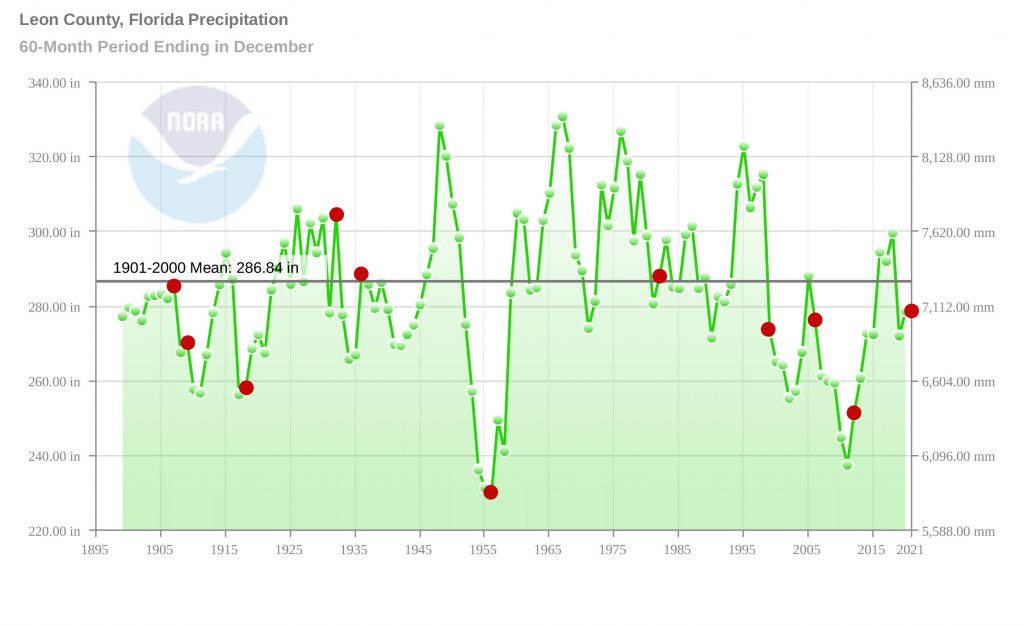

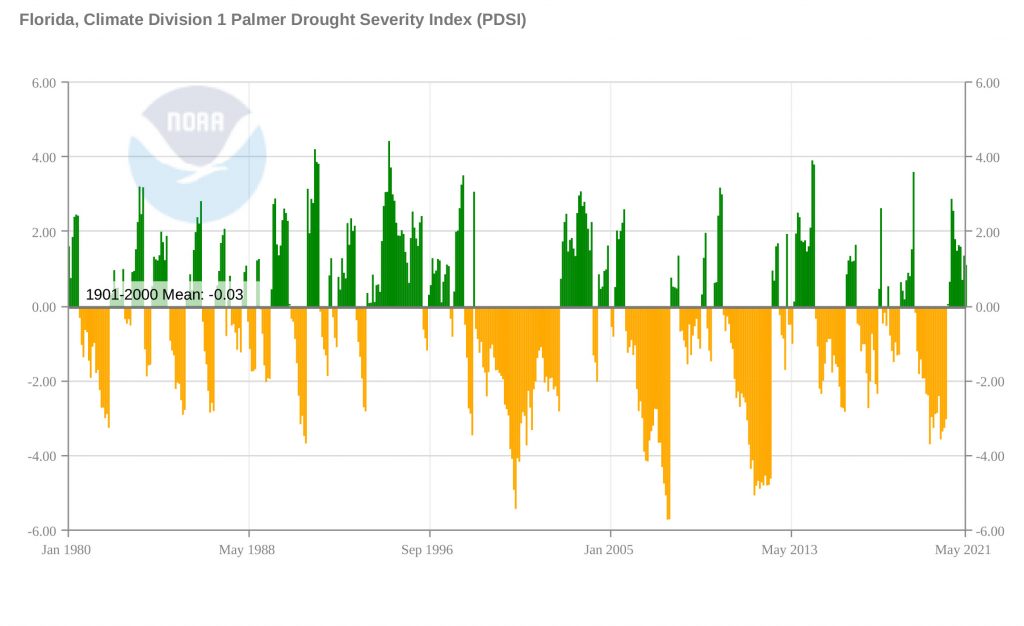

Looking at the graph above, we can see a rough connection between rainfall and Lake Jackson drying down. But is there a magic rainfall number that lets us know, without question, that Lake Jackson will drain? And what of the other lakes?

Is there a pattern to the lake dry downs?

Those are the questions that drove Jonathan Lammers to dig up newspaper articles and research papers dating as far back as 1829. From this, he compiled a list of every event related to dry downs and extreme high and low water levels. He also looked at available rainfall information.

Comparing rainfall tables from a 1961 master’s thesis to the newspaper records, Lammers saw one clear connection: “…any year where rainfall falls below 45 inches is more likely than not to correlate with a sinkhole opening in one of the lakes.”

It was less clear which of the lakes might drop.

“Overall, there does not appear to be any clear pattern as to the relationships between the lakes themselves. In other words, just because Lake Jackson drains, it does not mean that any of the other lakes will do likewise.” He did point out, though, that extended droughts saw multiple lakes dry down.

The aquifer beneath us is still largely a mystery. Divers can explore larger spring caves, and dye traces can tell us when two surface waterways connect underground. This is how we know that Porter Hole Sink is connected to Wakulla Spring, for instance.

I went to the Aucilla River Sinks with Harley Means earlier this year. This is a place where the roof over the aquifer has collapsed. Means showed us how water can move in larger channels, such as the sinks themselves. But he also showed us the cracks and holes- ranging in size from pinheads to soccer balls- in the limestone walls of the sinks. Water can move through and shape these as well.

Under Tallahassee, how many larger channels, smaller tunnels, cracks, and holes are moving water under or away from each of these lakes?

Lake Jackson After 1999

Let’s take another look at the graph above. Prior to 1999, there were two extended droughts that saw Lake Jackson dry down twice within the span of a few years. This occurred in 1907/1909 and 1932/1936. If we look at those as combined events, then the lake, going back before the start of the graph to 1829, usually drained every twenty-plus years or so. This changed in 1999.

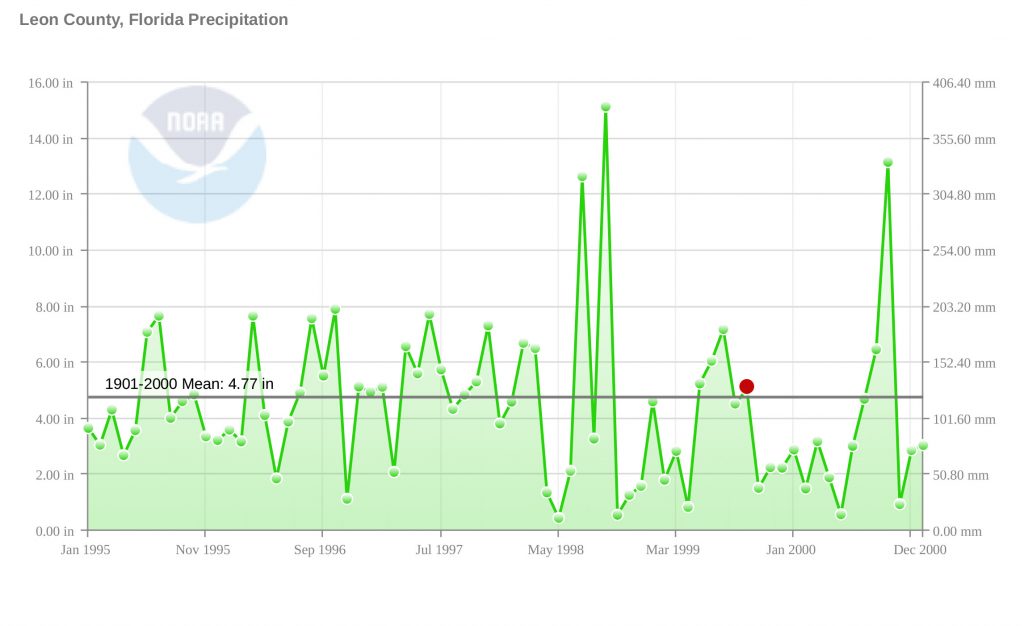

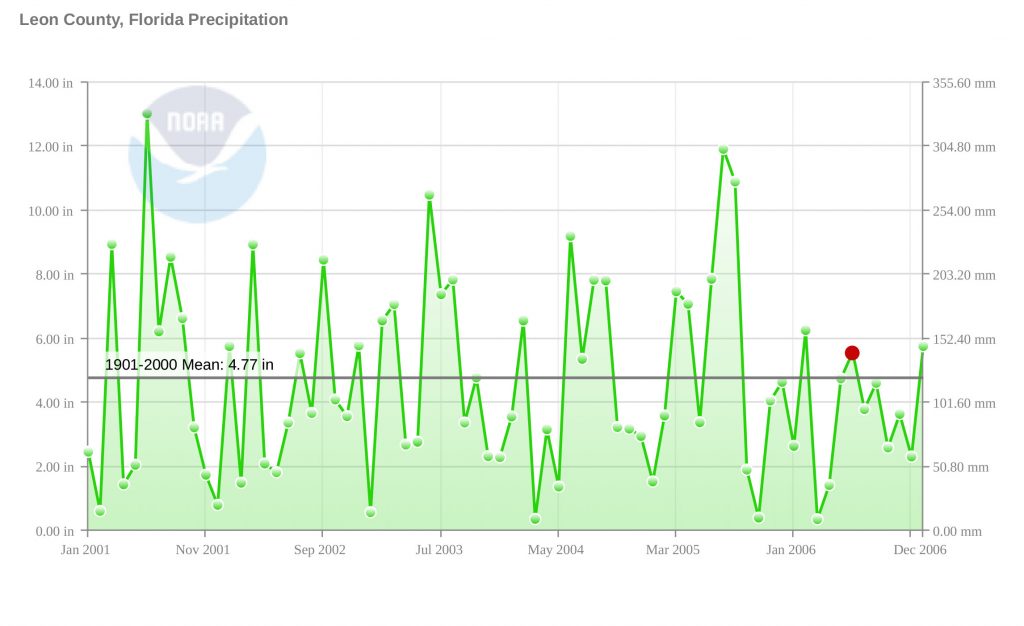

Lammers’ chronology shows a dry down in 1999, and another in 2006. The Tallahassee Democrat reported that the 2006 dry down was the fifth since 1999. The dry downs between ’99 and ’06 weren’t individually reported; this was an extended low period for the lake. You can see it in the longer term graph higher up, how little rain we received from the late 90s through 2015 or so. Zooming in a little, we can see that there were wet months during this period. The lake level rose a little and then fell, though perhaps the aquifer never got as full as it needed for the lake to hold water.

The lake dried down again in 2012, and now in 2021. The graph below shows drought severity between 1980 and 2021. The left side of the graph shows what had been a somewhat typical wet/ dry cycle. Some years wet, some years dry, with some wet or dry stretches lasting longer than others. Starting in the late 90s, longer, harsher droughts became normal.

These extended droughts have affected waterways from Apalachicola Bay to the ephemeral wetlands south of Tallahassee. Dry periods are normal in each of these settings, and because plants and animals have evolved with them, dry periods are necessary for a healthy ecology. But how will life adjust to recent, harsher climate trends?

Images from Porter Sink in Lake Jackson

Note the tire tracks in the images above, in the dried out lake bottom.