The last time I was here for an indigo snake release, it was the largest group they’d ever set free. In 2022, The Nature Conservancy of Florida and its partners released 26 eastern indigos into gopher tortoise burrows at the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve. The Preserve is full of burrows: shelter from cold, heat, or fire. One day, the young snakes will hopefully find a mate and nest in one. Wild breeding is a major goal of the reintroduction project.

This year, they released 41 snakes and surpassed 150 total snakes over seven years of reintroductions. As preserve manager Catherine Ricketts explains, this means they can try something new. “The reintroduction plan said that once we had 150 [snakes] at the original release site, we could branch out.”

Since the goal is to have snakes out on the landscape making new snakes, they’ve all been released in a single section of the Preserve. Concentrating the snakes makes it easier for them to find each other, and late last year, they had proof that the strategy was working. For the first time, two wild-born indigo snakes were found at ABRP.

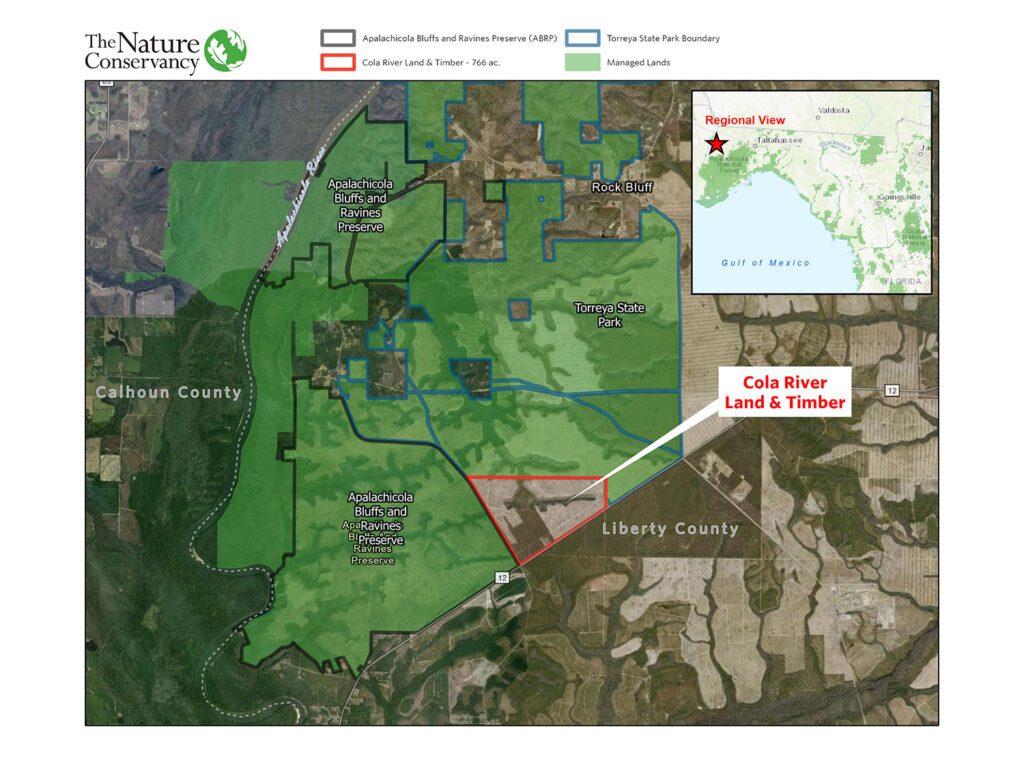

On Tuesday, I accompanied Catherine to a new release site. It’s across a steephead ravine from the original, and yet not far from where one of the wild-born snakes was found. So, we see they move across the landscape. The ability to spread out is a major reason project partners chose ABRP as a release site. Combined with Torreya State Park and the Beaverdam Creek Wildlife Management Area, the snakes have over 22,000 acres to roam.

Space for indigo snakes to roam

Let’s imagine an eastern indigo snake traveling away from its release site. It starts its time at ABRP in a gopher tortoise burrow dug into a sandhill. A sandhill is an ancient beach dune, a relic from a time when sea level was much higher. This is the upland: a hot, dry place, and one that relies on regular fire to maintain an open landscape.

The indigo searches for food. Indigo snakes eat other snakes, predators such as rattlesnakes, cottonmouths, copperheads, and rat snakes. This apex predator is nonvenomous but has no problem consuming its venomous prey, prey that is often down in steephead ravines. Wet, shaded ravine forests are full of food for snakes, and snakes that eat snakes.

One hundred and fifty indigos have been released in this section of the Preserve. Their proximity makes it easier to find a mate, but potential mates and romantic rivals are also hunters competing for available food. A snake might decide to range out.

I mentioned earlier that the snakes had 22,000 contiguous acres to roam, but it is 22,000 acres crisscrossed with roads. And there are a few gaps. One of those gaps was across from the first road an indigo snake encounters to the east of the release site. Recently, the gap was closed.

Cola River Land & Timber property becomes a part of Torreya State Park

In March of 2024, The Nature Conservancy helped facilitate the purchase of the 758-acre Cola River Land & Timber property. The land will be added to Torreya State Park, enlarging the Sweetwater Creek restoration area. I produced a segment on the restoration area a few years back. It’s a 7,000-acre tract of land, over 4,000 of which is in the process of being converted from sand pine timber land to a longleaf pine-based sandhill ecosystem.

The Nature Conservancy has been helping restore the Sweetwater tract, clearing 300-acre parcels of sand pine, seeding wiregrass, and planting longleaf seedlings. Longleaf pine takes decades to mature, but the open understory of the habitat is already suitable for gopher tortoises to dig burrows. Those burrows may one day become indigo nests.

“We’ve talked with the park about what they might want to do with the property and how we can help them as far as whatever restoration work they want to have completed,” Catherine says. “So it’ll be collaborative, but ultimately, they’re the decision maker.”

Unlike the rest of the Sweetwater Tract, Cola River won’t need to be totally cleared. The property already has young longleaf pines growing on it, as well as open, grassy areas. You can see this in the photo above. And behind the pines, you can see an area of dense hardwood trees. This might be the most ecologically interesting part of the property.

Sweetwater Creek Ravine

If you look at the map below, you can see dark green tentacles reaching into the lighter green areas from the upper left. This is a steephead ravine system known as Sweetwater Creek. If you’re new to the blog and have never heard of a steephead, you can check out my previous posts on steepheads.

The quick take is this. Steephead ravines are, wait for it – steep. And also narrow. They are shady pockets full of rare and endemic flora and fauna. If you geek out on plants, check out this segment I filmed in Sweetwater Creek. Steephead ravines are a feature unique to north Florida.

With the Cola River purchase, Sweetwater Creek now sits entirely on conserved land. This protects its watershed, the sandhill where water sinks down and seeps into the ravine creek bed. The action of water seeping from the creek bed means that steepheads erode from below, which accounts for their distinctive narrowness. Sweetwater Creek drains into the Apalachicola River.

Each tip of the ravine is actively (but slowly) eroding away from the river, where the creek originated as a small trickle millions of years ago. In 2017, we visited Sweetwater Creek with Bruce Means. He showed us how much one theater had advanced in the 50 years since he first climbed into it.

Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines

- The eastern indigo snake: updates on releases, breeding of this endangered apex predator at the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve.

- Alum Bluff is the largest geological outcropping in Florida, full of fossils telling a story of Florida over 20 million years in the making. This includes fossils of the largest shark to ever swim in Earth’s oceans.

- The Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines region is one of the top biodiversity hotspots in the United States.

- A restoration project at Torreya State Park is adding thousands of acres of habitat to the region.

- Hike a trail unlike any other in Florida – ABRP’s Garden of Eden.

How many indigo snakes are out there?

Restorations and land acquisitions are giving indigo snakes more high and dry places to sleep and nest, and more low and wet places to hunt. The snakes should have the elements they need for a successful life. But how do project partners know that they are thriving and reproducing? After all, 22,000 acres is a lot of ground to cover for a handful of staff and volunteers, especially for a snake that might be in a burrow or ravine.

When I wrote about the young wild-born snakes last December, I learned about the various ways the Orianne Center for Indigo Conservation monitors indigos here. There’s a lot of hiking the sandhill and checking around tortoise burrows. Doing this last year, OCIC biologist Michelle Hoffman found 15 adult snakes, in addition to finding one of the wild-born juveniles. “That is the most unique individuals she’s found in a single survey season,” said Catherine Ricketts.

There are also increasingly more cameras throughout the preserve. Some are on drift fence traps, physical barriers that lead a snake to a spot where it triggers a camera.

Many of their cameras are mounted outside of gopher tortoise burrows. These are not motion-activated; the snakes are dark and might get lost at night or in a shadow. Instead, each camera takes an image every thirty seconds, all day, every day. With all that visual data, they’re sure to have plentiful images of indigo snakes. All someone has to do is sort through millions of photos.

So far, that person has been Michelle Hoffman. Catherine shared an update on a project that would let citizen scientists lend her a hand.

Indigo camera Zooniverse update

In December, I shared that TNC and its partners were going to upload burrow-cam photos to Zooniverse. This is a platform where citizen scientists can peruse photos to look for indigo snakes.

“We’ve moved past the beta testing period, where we were trying to establish baseline parameters for accuracy and retirement of the photos,” Catherine said. “There has to be a certain level of agreement from all of the people who have looked at the photo and said, ‘Yes, there’s an animal. No, there’s not an animal.'”

This sounds similar to iNaturalist, where a certain percentage of users must agree on a species identification for it to be considered “research grade.” Because any one user might make the wrong call, it helps to have multiple users review a photo. The project partners have now decided how to define their version of research grade, and their project is now going through the Zoonivserse internal review process.

Catherine has been told that the project would be live within one to two months.

By the numbers

Eight releases. Over one hundred and fifty snakes. At least two wild-born snakes. Twenty-two thousand acres and growing. Numerically, the eastern indigo reintroduction at ABRP is looking solid. And while the snakes are not released in an area open to the public, people are more and more likely to see them. Maybe it’ll be on Zooniverse, from the comfort of your home. One of the wild-born snakes was found near Alum Bluff, not far from the Garden of Eden Trail. So, perhaps you may encounter an indigo while hiking to the best view of the Apalachicola River.

Within a few years, who knows? Maybe you’ll find an indigo snake while hiking at Torreya State Park. There’s no telling. Personally, the most exciting part of the reintroduction project is that the snake population will grow as the longleaf habitat starts to take shape around Sweetwater Creek. It’s an ecosystem that will take hundreds of years to be fully mature, but within our lifetimes, it will grow quite a bit.

I’ll keep checking back on the snakes and on the restoration. My dream is that WFSU Public Media is still here in 300 years, and will continue to document the restored landscape and the indigo snakes reproducing to fill it. It would make quite the documentary.