A moment long awaited has come for The Nature Conservancy and its partners: at least two eastern indigo snakes were born at the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve this year. After seven years of releasing captive-bred indigos here, there is, for the first time, evidence the snakes are reproducing. It’s a major milestone for a snake that had all but disappeared from the Florida panhandle.

The Preserve, owned by The Nature Conservancy, covers 6430 acres. It’s a landscape dominated by longleaf pine and wiregrass, and maintained with regular fire. At ABRP, longleaf habitat sits upon the tallest sandhills in Florida. Carved into those sandhills are steephead ravines, home to rare and endemic plant and animal species. Sandhill and ravine ecosystems make the region a biodiversity hotspot, yet preserve staff didn’t find the first hatchling in either.

“Well, the first snake was actually remarkably, you know, unremarkable,” says Preserve Manager Catherine Ricketts. “One of my co-workers was pulling up to the shop in a tractor, and the snake was laying there basking in the sun on the little concrete driveway of the shop. It was like, ‘Look, here I am.'”

They sent photos of the snake to Michelle Hoffman, a field biologist with the Orianne Center for Indigo Conservation. She confirmed it was a juvenile indigo, about three months old. Not long after, Michelle was conducting surveys about two miles away, near Alum Bluff, when she found a second hatchling. This is a setting where one might expect to find a rare snake – outside a gopher tortoise burrow deep in the forest, near Florida’s largest geological outcropping, overlooking the Apalachicola River.

Now they have found two wild-born snakes, but there are likely more. The question is – how many?

Why release indigo snakes?

I recently chaperoned a field trip to the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve. When I mentioned to another chaperone that I’d participated in a snake release here, she did a double take, “I’ve never heard of people releasing snakes before.”

The eastern indigo (Drymarchon couperi) isn’t just any snake. It’s a nonvenomous snake that eats venomous and nonvenomous snakes – an apex predator. Apex predators maintain balance in an ecosystem by limiting their prey species, in this case, snakes that eat songbirds and small mammals.

Indigo snakes have all but disappeared in north Florida, and are declining throughout their range. Because of this, they are federally listed as Threatened. Their populations are healthiest in south and central Florida, but north of that, they need longleaf pine habitat. When maintained by frequent fire, the canopy beneath the pines is open and grassy. It’s an ideal groundcover for gopher tortoises, whose burrows keep indigo snakes warm in winter and provide a place for them to nest in the summer.

Longleaf habitats once covered 90 million acres in the American southeast, much of which was clear-cut over the last two hundred years. After reaching a low of three million acres, restoration projects have raised the number to around five million.

The Nature Conservancy started restoring this property about forty years ago. Over the last twenty years, they’ve partnered with the state to restore about 4,000 acres adjacent to their property, in Torreya State Park. Also next to the Preserve is the Beaver Dam Wildlife Management Area, which protects the Apalachicola River floodplain downslope of the sandhills. In the summer, low, wet, shady areas like steepheads and floodplain forests are full of indigo prey.

The three properties provide several thousand acres for gopher tortoises, indigo snakes, and various other animals, which is why Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines was chosen as one of two indigo snake release sites in the country.

Are these the first indigo hatchlings at Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines?

The Nature Conservancy and its partners have released 126 indigo snakes at the Preserve since 2017. The snakes are hatched at the Orianne Center for Indigo Conservation at the Central Florida Zoo. The facility raises only two animals: indigos, and another animal we know and love on the WFSU Ecology Blog: the striped newt.

Orianne raises the snakes for almost two years, releasing them just before they become sexually mature. Once they’re on the landscape, they’re on their own. Still, project partners keep track of the snakes as best they can. By regularly checking, they can see if the snakes are ranging away from the release site, if they’re surviving, and if they’re making new indigo snakes.

The two recently born snakes were found about two miles apart, by Michelle’s reckoning, and with a steephead ravine between them. One was north of the release site, the other to the south. Odds are the snakes are from two different broods, and each likely has siblings. They’re not an easy animal to find, so we wonder: for every animal we see, how many more do we not see? And, are these even the first hatchlings at ABRP?

“Even with us finding two, that doesn’t mean that there weren’t hatchlings in previous years,” Catherine says. “It could mean that we just didn’t find them.”

Let’s take a look now at the different ways TNC and Orianne find their indigo snakes.

Tracking the eastern indigo on foot

Three years ago, I tagged along on an indigo snake survey. They’re most easily observed in the winter months, on sunny days when it’s cool but not freezing. On days like this, the snakes come up from gopher tortoise burrows and heat up their cold blood. It’s warm enough for them to come out and catch the sun, but cold enough that they don’t stray far from the burrow.

We split into teams and walked in three different directions away from the release site. The Nature Conservancy places fluorescent flags by gopher tortoise burrows, and we made our way from one to the next. We found one snake that day.

Michelle is out doing surveys now, and she confirms that any day you see any snake is a good day.

“We’ve gotten three recaptures of indigos this week,” Michelle says. “But you know, there are plenty of weeks that we go out, and I go out, you know, every day for seven or eight days, and I don’t find anything.”

In the last couple of years, they’ve added new ways to look for snakes. Technology is helping them keep an eye on the forest day and night, every day of the year. It’s a lot more work for Michelle, but soon you – yes you – can help search for eastern indigo snakes.

Scanning millions of photos, some of which have indigo snakes in them

During the 2022 release, we saw that many gopher tortoise burrows had been equipped with cameras. Indigos are released directly in front of burrows, and most slither right in. Pointed at the area in front of the burrow, the apron, cameras snap photos every thirty seconds. If a snake leaves the burrow at sunrise, there may well be an image of it.

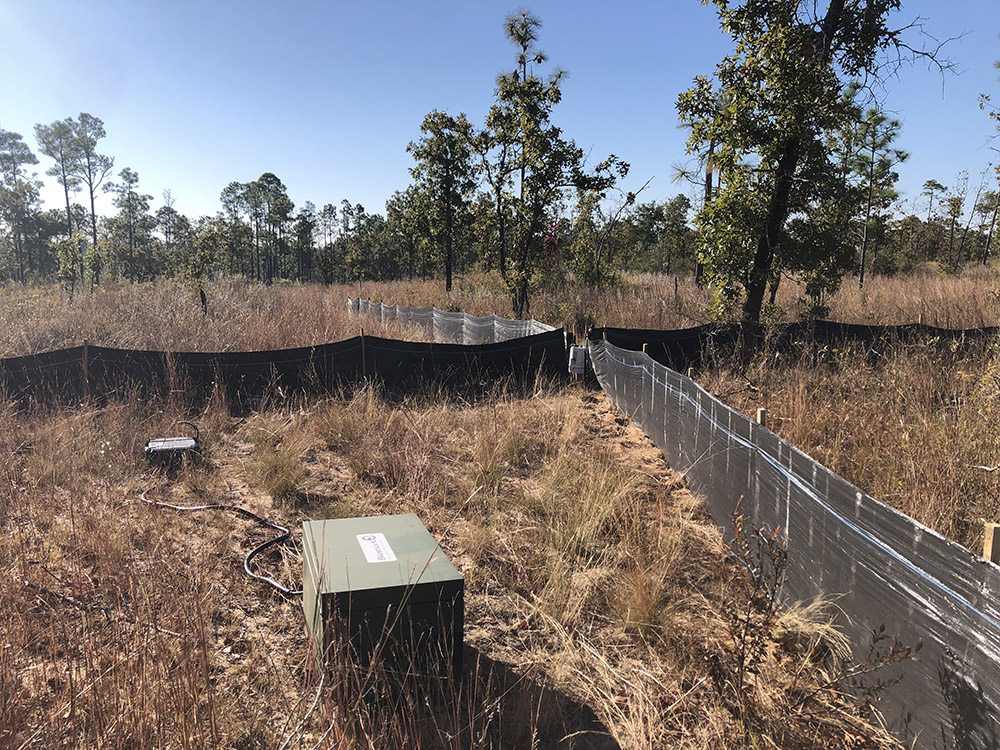

Later that year, they deployed drift fences around the release site. If you’ve read our striped newt stories, you may have an idea of how the fences work. A snake or any animal that crawls on the ground runs into a fence and follows it. Striped newt fences trap the newt in a bucket, which requires someone to physically check the fence once a day to record and release them. The “trap” in this array is a motion-activated camera. There’s also a scanner that detects and identifies the PIT tags implanted on released snakes.

“A neat thing about the camera traps at our drift fences is that it takes a picture of the snake from the top down,” Michelle says. “Every time we do a release, we take photos of the head of the snake. So we take a photo of the side of the face, and from the top.” Reviewing photos from the bucket traps, she has matched the scale patterns on the heads of three snakes with their release photos. Knowing the identity of the snake lets them know how each snake is moving on the landscape.

There’s a lot of information in the camera trap images, yet most of the photos show no activity at all. It takes people-power to sort through them all. Since they deployed the cameras, Catherine Ricketts estimates they’ve captured seven million images. Michelle Hoffman has already worked her way through almost half of those images.

What if Michelle had some help sorting images? That’s where you come in.

Soon, you’ll be able to find indigo snakes, too

“It can get really monotonous looking through all those pictures,” Michelle says. “And there’s just nothing exciting popping out. So that’s when you start to get droopy eyes, you know. But we’re going to be starting up a volunteer program pretty soon. That will help us get some citizen scientists on board to help review photos.”

The indigo release program is in the process of setting up a project on Zooniverse, a citizen science platform. Zooniverse is built to allow a person with no scientific training to search images for whatever it is researchers want to find. One project has you count spider crabs in underwater time-lapse images, another has you searching the stars for pulsars. Or, you can search handwritten Argentine naval records from the 1800s, and transcribe weather and oceanographic information.

Scanning gopher tortoise burrow images, you may see any of the three hundred animals that use them for shelter. And you’ll see a lot of nothing. Your reward will be to help biologists understand the snake and how it’s getting along in one of our nation’s biodiversity hotspots.

Look for the Zooniverse project to launch within the next few months.

Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines

- The eastern indigo snake: updates on releases, breeding of this endangered apex predator at the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve.

- Alum Bluff is the largest geological outcropping in Florida, full of fossils telling a story of Florida over 20 million years in the making. This includes fossils of the largest shark to ever swim in Earth’s oceans.

- The Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines region is one of the top biodiversity hotspots in the United States.

- A restoration project at Torreya State Park is adding thousands of acres of habitat to the region.

- Hike a trail unlike any other in Florida – ABRP’s Garden of Eden.

Indigo snakes dig, too

Michelle Hoffman has spent years observing indigo snakes, both at the Orianne Center and in the field. I ask her if she’s learned anything surprising from all her observations.

“I guess I’ve been really surprised that everything that I’ve read in the literature has been really accurate with the indigo,” she says. With any wild animal that hasn’t been extensively observed, biologists will find behaviors that don’t match up with what has already been recorded. Not so for the indigo, with one exception. Michelle is writing it up for a herpetological journal.

“Indigos would actually dig, make their own holes to get underground under some sort of like vegetation,” she says. “They would actually use their heads and dig these holes all over the place in those enclosures to get underground.”

She first saw them do this at the Orianne Center, and then in the field. Indigo snakes are not currently known as excavators.

“I’ve also come across at least one indigo here while doing radio telemetry back in 2017, ’18, ’19, around there, where the indigos are using the root systems of wire grass, or hollowed-out tree stumps of burnt pines and oaks.”

In his fifty-plus years of observing eastern diamondback rattlesnakes, Dr. Bruce Means found that diamondbacks also use tree stumps for shelter. Indigo snakes eat eastern diamondback rattlesnakes.

There’s still much to learn about the underground lives of sandhill animals. In a gopher tortoise burrow, she says, a scope camera will pick up small side tunnels made by other animals, and connections between burrows. “It’s like, yeah, this is a pretty complex system that’s going on here.”

The future of indigo snakes at Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines

For the first time in decades, indigo snakes are reproducing at ABRP. A new generation of wild-born indigos is slithering in sandhills, and down into ravines. The Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve is one step closer to not needing to have snakes released here.

That day is a few years off, but the snakes seem to be on their way to a self-sustaining population. And it’s happening sooner than Michelle would have guessed.

“I wasn’t expecting as much success as early as it’s happened, and I think that that’s really saying something to not only the reintroduction and the process of reintroducing that we’ve been going through for the last seven years, but also our monitoring.”

For now, releases will continue, as will the monitoring. Who knows, maybe you or I will be the next to find an eastern indigo snake hatchling.