It is ten weeks until the Tallahassee Marathon and so I’ve been hitting the trails…on my bike. For the past two years, my husband has run our city’s half marathon—a race that starts at the capitol building and wraps around Lake Ella, then Cascades, then Doak, before it dumps runners in College Town. This year, he’s leveling up to a full marathon, an undertaking that means that most of his Saturdays are spent running up to fifteen miles.

Before my husband became a runner, we’d spend our weekends walking. With our long-haired dachshund leading the way, we’d stroll beneath the oaks festooned in Spanish moss at Elinor Klapp-Phipps Park or make our way south of town to meander past the wet and dry sinks that dot the Leon Sinks Geological Area hiking trail. When his new running ritual effectively eliminated our walking ritual and we still wanted to spend time together outside, he came up with Bike and Run days: he runs, I bike alongside him.

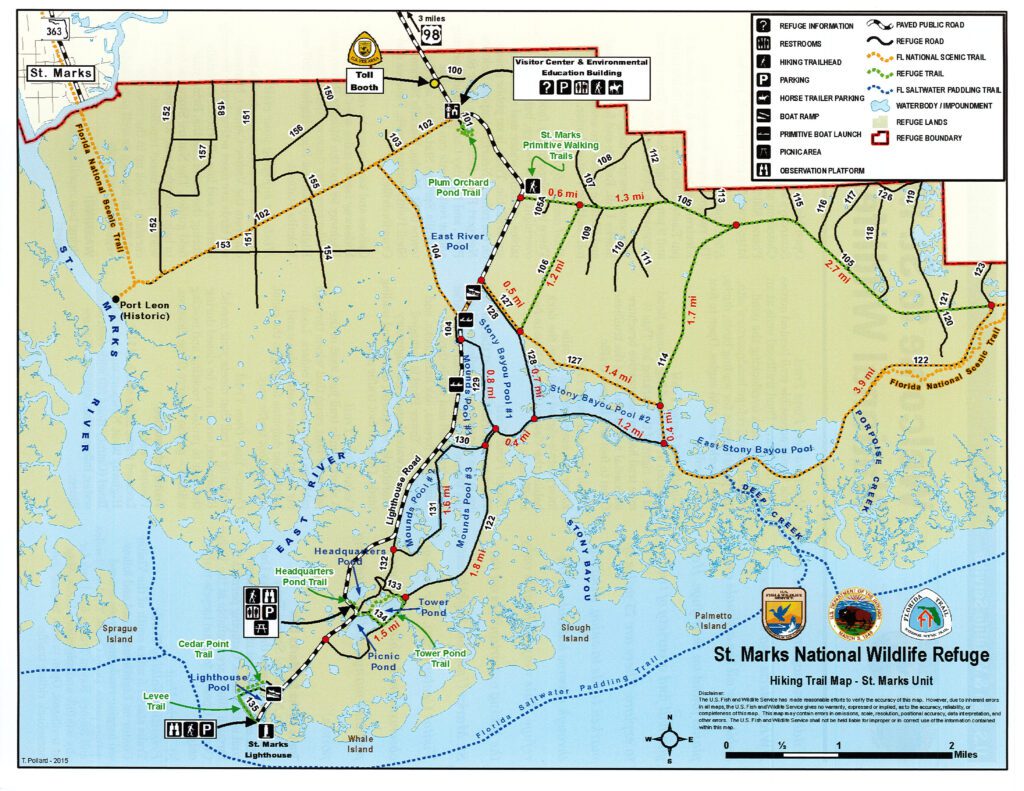

We’ve tried our Bike and Runs at many different places in town. In and around Tallahassee there are many trails that are long enough to support long-distance treks including the St. Marks Historic Trail, Miccosukee Greenway, or Old Centerville Road—an orange clay canopy road that meanders past northern Florida’s piney plantations and is popular with long-distance runners. We’ve found though, that the place that works best for us is St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge, where paths stretch deep into wilderness, past freshwater ponds, saltwater flats, and pine forests.

Leaving Lighthouse Road, and Deeper into the St. Marks Refuge

Before starting our Bike and Runs, my husband and I frequented St. Marks. I’m a birder and so we’d drive down the refuge’s asphalt road, stopping frequently for short walks around the Mounds Pools or along the gulf beaches abutting the lighthouse—our dog desperately trying to bite the fiddler crabs that swarm the shore at low tide. We’d see otters dipping in and out of the creeks that run alongside the East River Pool and we’d watch boats speed by as we stood at historic Port Leon, looking out across the St. Mark’s River. But there is only so far you can go on foot, and so, our walks would not take us all that far from the road itself. One of the things that I find exciting about the Bike and Runs is our ability to go deep into the refuge, on trails that we rarely see other people, where it feels like we have escaped into a wilder, more mystical part of Florida.

Now, as the fall transitions into winter, is one of the best times to head deep into the refuge. The temperature has started to cool off (although I still recommend getting an early start as it feels hotter out there with the lack of shade and stagnant Florida air), and the birds are coming to the refuge in droves. When I stopped at the refuge visitor’s center on my way in, one of the volunteers working there handed me a map, drawn in with the birds you are most likely to currently see. Overwintering ducks are returning to the refuge like buffleheads, green-winged teals, and Northern Shovelers. Waterfowl congregates in massive numbers at the lighthouse ponds, and it’s amazing the sheer numbers of species you can see floating there. On my way into the refuge, I also saw one of the resident bald eagles perched on his massive nest right where pine trees give way to marsh, and where I parked, by marker 104, I watched a northern harrier swooping across the water, the white band on its tail a flash of light amidst its dark brown body. With so much to see right off the refuge road—ducks and egrets and herons and alligators and birds of prey—it raises the question: why venture far from the road at all?

Deeper in the refuge, I see more of the same: more alligators sunning themselves on the bank and more clusters of overwintering coots—little black dots floating en masse atop the water that migrate to Tallahassee in the winter. I also found I startled more animals—animals that didn’t expect to see me there. More than once, I pedaled to a lone pine tree or a thicket of grasses growing along the water and disturbed a Great Blue Heron, an experience that allowed me a chance to understand the sheer size of the bird. Up close, the heron is large and gangly. Deep in the refuge, on the far side of Stony Bayou #2, I have also observed flocks of roseate spoonbills and wood storks, their numbers far greater than anything I have seen close to the refuge road.

Navigating the Refuge Trails

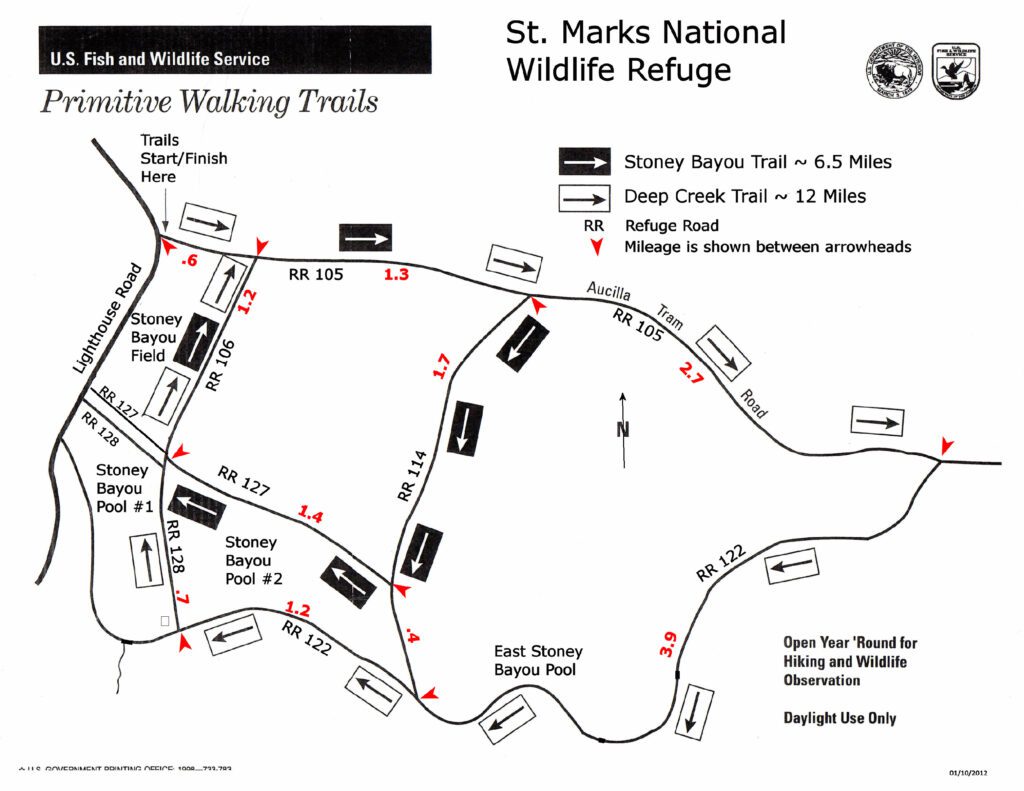

I’ve tried to walk and bike many of the trails at St. Marks and I’ve learned that the maintenance of the trails can vary considerably. This means that if you strike out on the trails, you may find some more accessible than others. Because there are so many trails, however, if you find a trail inaccessible, you can always turn around and try a different one.

A trail that is not mown is difficult to bike, as are trails that have been rooted up by hogs. I tried biking trail #127, which follows the north side of Stony Bayou Pool #2, and found it too difficult because of all the ruts created by hogs. I’ve found trails 122, 104, and 102 to be fairly maintained. Trail #127 was a grassy dike and so it was relatively easy for hogs to rut around and turn up the dirt, whereas trails 122, 104, and 104 are made of a compacted sand—a material that is easier to bike on and less interesting to hogs. These trails are also more frequently used than some of the other trails in the park. For instance, trail 122 is used for the refuge’s wildlife and birding tours. These tours, which run on Saturday mornings from late fall to early spring, are free (once you pay to get into the refuge). Visitors are driven around the refuge to bird, led by refuge volunteers. On our Bike and Run, my husband and I ran into one of these tours.

On my most recent Bike and Run, I parked at gate 104 and took 128 to 122, circling back along the lighthouse road, before I took 122 out past Stoney Bayou Pools 1 and 2 and the East Stony Bayou Pool. Because these trails meander past plenty of water, I saw ample megafauna, and the trails themselves alternate between the compacted, gravely sand, which is easiest to navigate on a mountain bike, and mowed grass that is slightly more challenging but still very doable if there hasn’t been hog activity.

As path 122 overlaps with the Florida National Scenic Trail out past the East Stony Bayou pool, I often see feral hogs. The Florida National Scenic Trail, frequently shortened to the Florida Trail, is a roughly 1,500-mile federally designated trail that invites hikers to trek across the entire state, from the Big Cypress National Preserve in south Florida to the Gulf Islands National Seashore, on the panhandle. We’re lucky, in St. Marks, to have some of the most beautiful and accessible sections of the Florida Trail. Out on this trail, I’ve seen lone hogs and families—once I saw a family, piglets and all, swimming across the bayou pool before they emerged from the water and disappeared into thick vegetation. Seeing the hogs can be unnerving, and it’s important to practice hog safety—giving them plenty of space, especially when they have young.

One of my favorite sites to cycle past is a campground for through-paddlers on the Florida Circumnavigational Saltwater Paddling Trail—a trail that follows the entire Florida coast from Pensacola to just below Savannah, Georgia. The campground is off the Florida Trail, near where Deep Creek cuts towards the mainland. Using the campground requires a permit and is only for through-hikers and paddlers (those attempting to complete these trails in full), but in the winter, when bugs are minimal, the campground looks idyllic, tucked away behind a small pond surrounded by a hammock of palmettos. With the Spartina grass and palmetto fronds in the background, it couldn’t look more Florida.

Enjoying Fall Wildflowers and Migratory Birds

All along the route, I’m astounded by the landscape. The waters teem with birds, and as happens in our glorious fall, the pathways are bordered by blooming grasses and wildflowers—goldenrod, pinky muhly grass, Bidens alba, and dozens of others. In the distance, behind the Stony Bayou pools, I see groves of palmetto trees, their trunks tinged in black from recent burns, and if I bike far enough, the Florida Trail will dump me into a longleaf forest where I can spot woodpeckers and flycatchers.

The outings feel both like an independent activity and a collaborative one. As a biker, I’m faster than my husband is on foot, but I also make frequent stops to get a closer look at birds through my binoculars. I’ll sit and bird and my husband will catch up, passing me by briefly. We alternate between chatting and being in our own worlds, and we’ve found a way to reclaim our weekend outdoor adventures together. The beautiful thing about Tallahassee is how versatile and plentiful its outdoor recreation can be and part of what I’m learning is how to use these ample spaces in ways that most suit what I’m looking for.